As the country prepared for World War Two, staff at the British Museum had to come up with a plan to keep the world's most precious objects safe from attack. On the 80th anniversary of VE Day, let's look back at how they did it.

On the 3 September 1939, the UK Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain addressed the nation on BBC Radio. Hitler had been given an ultimatum: withdraw from Poland by 11.00 that day or the UK would formally declare war on Germany... It was 11.15.

Eight days to evacuate

Chamberlain's words would have echoed through the halls and galleries of the British Museum, his voice amplified by the emptiness of the vast rooms. The galleries were closed to the public, and even if visitors had turned up, there wouldn't have been much to look at. Museum staff had been evacuating the collection since 07.00 on 24 August, and in just eight days (they took Sundays off) the team had already managed to evacuate over 150 tonnes of material.

The Magna Carta, Shakespeare's First Folios and the drawings of Michelangelo were now in the remote National Library of Wales awaiting the completion of a purpose-built, climate-controlled chamber being constructed in a nearby cliff-side.

The Rosetta Stone and the recently excavated Sutton Hoo treasures were in Aldwych tube station, which had been fully kitted out with humidity and temperature controls and was under 24-hour surveillance by two security guards. Those guards would spend the war in that tunnel, contending with damp mattresses, bedbugs and rats nibbling at their toes while they slept.

And the Museum's entire collection of coins was sitting in a butler's pantry in a country house in Kettering, Northamptonshire.

The need for speed

It took five years to move the British Museum's natural history collections to Kensington to create the Natural History Museum. The movement of manuscripts and books from the British Museum to the new British Library, completed in 1997, had been planned in one way or another since 1963. So how did the Museum pull this off?

Well, as with all great feats of British administration and logistics, it followed a handbook. And there just so happened to be the perfect little volume, published in June 1939 – Air Raid Precautions in Museums, Picture Galleries and Libraries – which was delivered to museums across the UK (and internationally) soon after it was published.

It should be noted at this point that in 1939 the British Museum was a museum, a picture gallery and a library all wrapped up into one. It's almost as though the handbook was written specifically for the British Museum, which isn't far from the truth... the Museum had in fact published it!

The final chapter of the handbook on protecting materials from air raids, was written by two members of British Museum staff: the Director of the British Museum, Sir John Forsdyke, who was the brains behind the logistics of the evacuation; and Dr Harold Plenderleith, the brains behind the science used to protect the collection.

The chapter is surprisingly brief, only 13 pages long. However, it punches well above its word count. Written as a clear set of instructions to be followed not questioned, it is full of detailed diagrams, lists of necessary materials (and alternatives for when those materials unexpectedly get requisitioned by the military), and a variety of options for housing your objects depending on the time and resources available to you. The guiding principles behind all this advice can be boiled down to a few key elements:

- Prioritisation: you can't save everything.

- Speed: you may only have a few days, even a few hours to evacuate your objects.

- Fire and explosives: if protecting your objects above ground, you must be able to contend with explosions and fire from incendiary devices (weapons or munitions designed to start fires).

- Moisture: if protecting your objects underground, you must be able to combat damp.

Let's break these principles down:

Prioritisation

Most museums around the world have always had some form of priority list for evacuating objects in cases of uncontrollable fire. These objects are, by necessity, almost always small and easily portable. As far as I'm aware, the Lewis Chessmen have been on our list since they joined the Museum back in 1832. This 'fire list' was the starting point for the Museum's evacuation, but it soon grew and became more ambitious.

Objects too large to travel were sandbagged in galleries where they stood.

Smaller, portable objects then needed to be prioritised. The following is taken from the Keeper of Oriental Antiquities and Ethnography Hermann Braunholtz's account of his department's evacuation procedure:

since at no time was there certainty of more than a few hours freedom from air attack, it was necessary to plan the packing like a retreat, withdrawing collections now from one gallery now from another as each became the most important part of the collection remaining. In the drawing up of the original list it had been our endeavour to take an international view… such things as would be a world loss… it was afterwards possible… to include in our lists some representative of every part of the collections.

– Hermann Braunholtz, 3 November 1939

I really feel for Braunholtz. Imagine being in charge of a team of curators who each think their area of expertise is both the most interesting and most important thing in the world. Now imagine getting them to all select only a small group of objects to evacuate, and then whittling down those lists, probably excluding one curator's objects for another's.

Now that the Museum had priority lists for various scenarios, they needed to actually move them – and fast.

Speed

Today, the British Museum loans more objects internationally than any other museum in the world. But up until the 1960s, it required an act of Parliament for even a single object to leave the Museum's premises. So we had very little experience moving objects, let alone doing so under the looming threat of aerial bombardment. A method had to be invented. Forsdyke's plan was ingenious and simple. A combination of 'no-nail' boxes and railway containers.

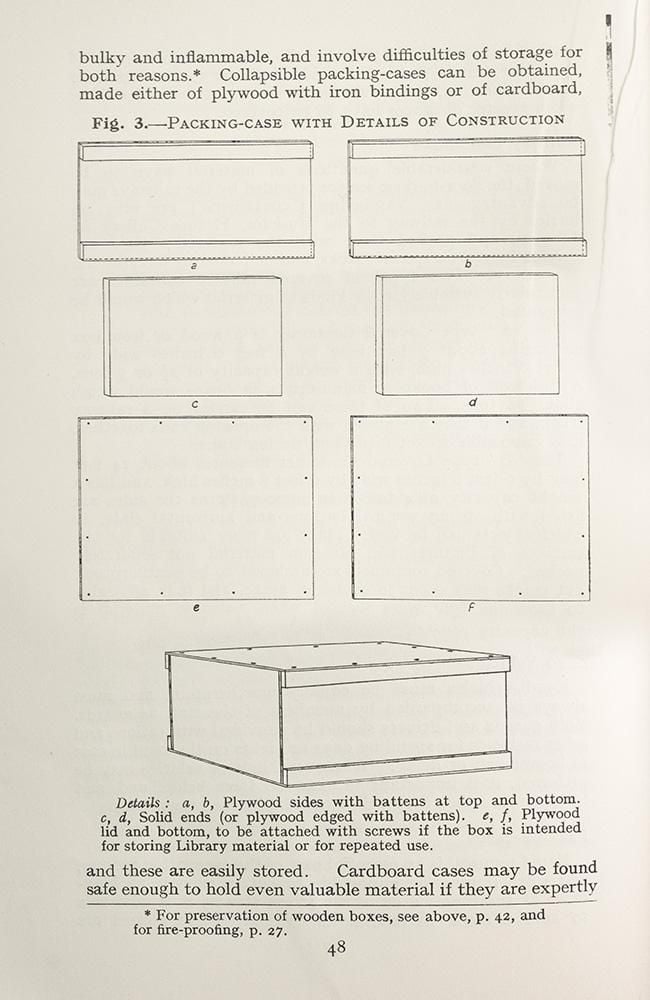

The no-nail box was a relatively recent invention that was revolutionising the shipping industry. Made of plywood with flexible metal edging, the boxes arrived flat packed (like Ikea furniture) and could be constructed in under a minute (less like Ikea furniture).

Forsdyke ordered a large quantity of these boxes to be delivered to the Museum for a 'rehearsal' evacuation in September 1938. However, on rehearsal day, the Director was horrified to discover that the delivery had been requisitioned by the British Admiralty. It also appears that the railway companies didn't provide railway containers that day either…

Forsdyke came to the conclusion that nothing should be left outside of the direct control of the Museum. So he ordered a series of railway containers to be delivered to the Museum and to be kept on-site, and ordered another 3,300 'no-nail boxes', which were stored from floor to ceiling in the Parthenon Gallery basements. I'm sure this event is the reason Forsdyke included a guide to constructing your own plywood packing crates in the Air Raid Precaution Handbook.

Packed into no-nail boxes, and travelling by train or horse-drawn cart, the objects now had a way of getting to safety. The only job left was to ensure they were safely stored once at the repositories.

Fire and explosives

The above-ground storage selected for the British Museum consisted of a series of country houses, all at least two miles away from any likely target of aerial bombardment, and with large ponds or lakes that could be used to put out fires, should they be hit by incendiary devices.

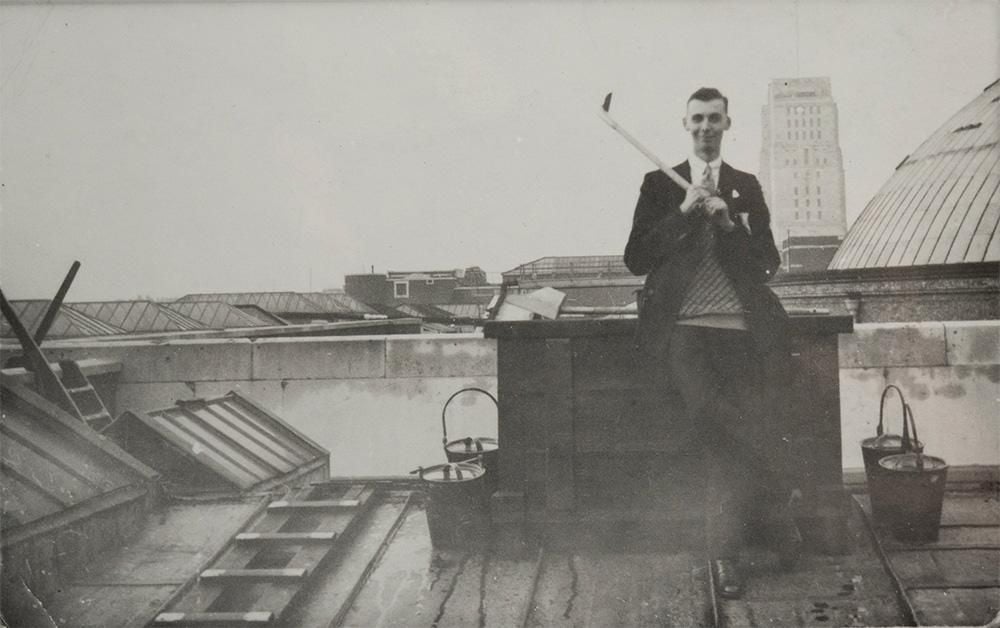

The British Museum had staff trained to deal with fires on-site since the 1800s. In preparation for the inevitability of a second world war, the number of 'fireman warders' was increased and provided with explosives-and-incendiary-device-handling training. Some fireman warders were sent to spend the war in the country houses, but most of them lived on the main Museum site, spending their evenings on the Museum roofs, facing down the Luftwaffe armed with a steel helmet, a bucket of sand (for putting out incendiary devices) and a golf club (for chipping incendiaries into buckets or off the roof entirely).

Damp

Deep, underground storage had the basic advantage of being beyond the reach of aerial attack. However, as anyone who's lived in a basement flat in London will know – damp will eventually destroy everything you own. Forsdyke was keenly aware of this, and while struggling to find suitable underground storage lamented: 'destruction by mildew, [is] slower but no less certain than that by bombs.'

But Forsdyke had an asset that most basement-dwelling Londoners do not: Dr Harold Plenderleith.

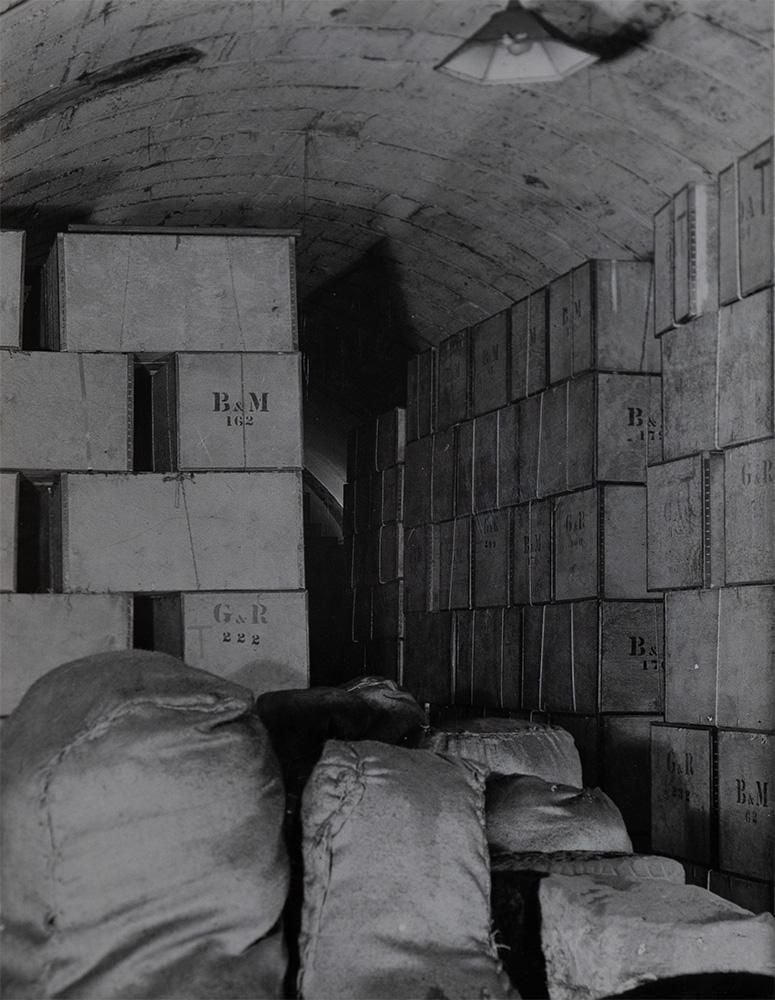

By the end of the war, the British Museum was making use of three underground repositories, Aldwych Tube Station in London (1939–1945), a purpose-built, underground chamber dug under the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth (1939–1945) and a converted quarry near Bath (1942–1946). Each was fitted to Plenderleith's specifications with hydrometres, air conditioners, heaters and ventilation systems and hand-powered back-up systems in case of power cuts. Each chamber had to maintain a stable environment of 60–75 degrees Fahrenheit and 60–65% relative humidity, with daily checks on environmental conditions and weekly reports sent back to Plenderleith throughout the war.

The storage in the quarry deserves a little elaboration, as it was without doubt the most sophisticated repository the British Museum had ever constructed. Westwood Quarry in Bradford on Avon near Bath was an old stone quarry that had most recently been used to culture mushrooms, until it was converted into a safe house for objects from the British Museum. The conversion began in 1941 and took nearly nine months: six months to level, support and waterproof the quarry and a further three months to dry out. Resources were scarce at this point in the war, so it was fitted with bomb-proof doors requisitioned from a London bank and, if the oral tradition of the British Museum is to be believed, the electrical equipment was powered by an old U-boat engine.

By the end of the war, this repository not only housed most of the British Museum's and V&A's collections, but also collections from the Bodleian Library (Oxford), Glasgow University, National Portrait Gallery, Royal Academy, the Wellcome Collection and Westminster Abbey.

The British Museum building had been badly damaged during the Blitz, particularly during the air raid of 10/11 May 1941 – so much so that the British Museum collections had to remain in the quarry for a full year and a half after the war ended in Europe. The staff charged with protecting the world's treasures had done such a phenomenal job that the old stone quarry once used to culture fungi would remain, while repairs to the Museum were being made, the safest place to store them. The objects eventually returned unscathed – having survived a world war – to a Museum and city that had been changed forever.

This blog post is heavily indebted to the work and support of Marjorie Caygill, Francesca Hillier (Senior Archivist) and Tom Hockenhull (Keeper of Money and Medals).