After 230 years away, a basketry hat was welcomed home to the Indigenous Chumash People of Southern California for an exhibition that marked a historic anniversary.

Tima Link, a Šmuwič Chumash weaver, textile artist and cultural educator, and Rose Taylor, Curator of North America collections, explain the significance of the homecoming and what happened next.

Researching and rebuilding

Tima Link: The Chumash are Native American people ancestrally from Southern California. Chumash territory spans more than 7,000 miles of island, coastal and inland landscapes: the four Santa Barbara Channel Islands and, on the mainland, from Malibu in the south to Morro Bay in the north and inland over the mountains into the Carrizo Plains and Tejon Valley. Today, while most Chumash people still live somewhere on their traditional lands, many Chumash people live in different states, as well as in different countries. In the past, people identified with a village or a region, but today there are 10 formal tribes of Chumash, each of which has its own unique history, language, traditions, governing bodies and goals for the future.

We are rebuilding the enormous cultural loss that colonisation brought to our shores, and a huge part of this is having access to our oldest cultural items, which are almost all housed in museums.

Rose Taylor: In Autumn 2023 I began a project working with members of the Chumash communities in Southern California. Thanks to funding from the British Museum's Museum Research Fund I was able to research the Chumash cultural belongings stewarded at the Museum and work closely with Chumash community members. The main collaborator for this project is Tima, who I first met in 2018.

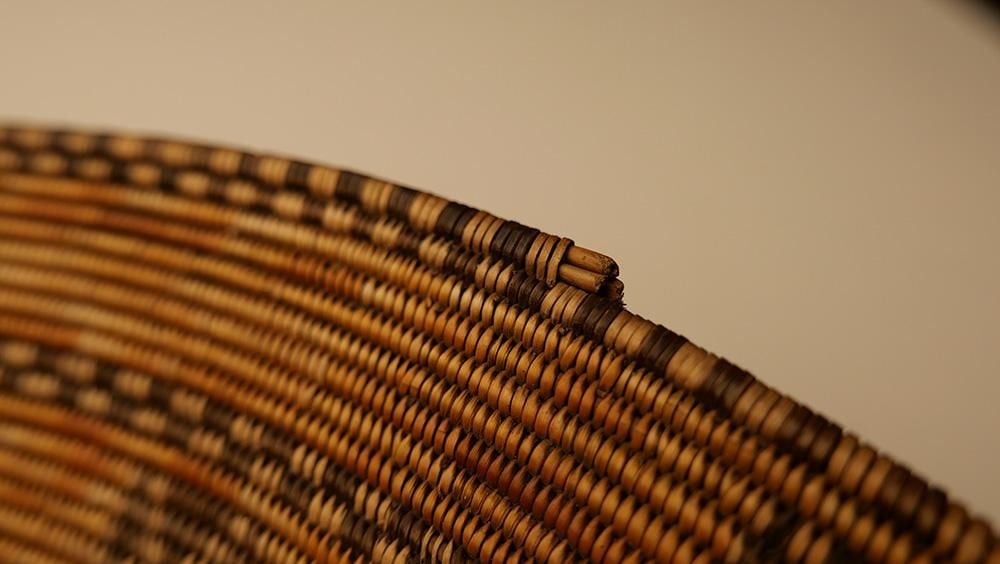

There are 13 objects in the Chumash basketry collection, including a basketry hat. These were collected during George Vancouver's expedition (1791–1795) surveying the Pacific Coast of North America, which reached California by 1792. The baskets' age, incredible artistry and collection history makes them a significant collection for Chumash peoples as well as for the Museum.

The project was a six-month pilot project which aimed to enhance the objects' collection records. This would include updating inaccurate or missing information about materials, attributions and location as well as adding information that reflects Indigenous knowledge systems and language. It was also important that my research led to more nuanced interpretation, display, collections care and conservation of the Chumash objects. Finally, an important outcome of the project was that we learn from and strengthen our relationship with members of the Chumash community. The project coincided with an exhibition at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles titled Reclaiming El Camino: Native Resistance in the Missions and Beyond, which would feature the basketry hat in its display. I had the privilege of couriering the hat to California, where it would be on display from January 2024 to June 2025.

Tima: Historically, museums have limited access to these items to academics and researchers, so having museums and curators open their doors to us is a gift – and a homecoming.

A weaver's knowledge

Rose: The first step of the project was photographing the Chumash baskets and creating a digital visual resource for community members, particularly for weavers. I spoke to Tima about this beforehand and her brief was to photograph the baskets in as close to natural lighting as possible in order to see gradation in natural dyes and how they have changed over time. She asked me not to edit or touch-up the images. Bradley Timms from the BM's Imaging department took the professional shots, capturing one side view and one aerial view per basket. I also took about 150 images to highlight the baskets' angles and curves, patterns, materials and close-ups of any reed damage or holes, and the basket starts and ends (ways of beginning the basketry, usually forming the centre of the base, and the end weave).

This type of visual information is very important for weavers in understanding how these baskets were made, attributing them to specific locations, communities or individuals, as well as for identifying the plants that were used and how the plant materials may have been treated before being woven (for example, dyed or dried). Tima also asked me to take selfies with the baskets so that their size and curvature could be understood in relation to a body, i.e. against the curves of my head and shoulders. I then uploaded these photographs to a website I set up for the project so that Chumash peoples and other interested stakeholders could access and study the basketry in more detail.

Restoring agency

Rose: In December 2023, I flew to Southern California for about three weeks to conduct research. This included hosting two community workshops, one at the Angeles National Forestry Headquarters in Los Angeles and one at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Across the two events, approximately 50 Chumash community members, people from other Indigenous groups and museum colleagues attended. The workshops focused on the Chumash basketry collection at the British Museum with the new photography as visual aids. The discussions centred around their collection histories and there was an emphasis on reidentifying and reactivating the basketry and giving them back their agency.

The Chumash basketry hat is one of a kind and dates to pre-1792. It was one of the main topics of discussion at these community workshops. Previously known as the 'padre hat', it was assigned she/her pronouns during the workshops and given a new name – or given back a name, I should say. Her new name was somelelu, a translation of 'sombrero' in the Šmuwič Chumash language.

Another project collaborator, Abe Sanchez (Purépecha) also helped to organise ethnobotanical workshops at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History's Sukinanik'oy (SBMNHS) Chumash Garden ('Sukinanik'oy' means 'bringing back to life' in the Šmuwič /Barbareño language of the Chumash) and in the Autry Museum of the American West's Native Garden. Abe showed us how to identify Native plants and those most commonly used by the Chumash, such as juncus reeds, deergrass, sedge, sumac, wild strawberry, elderberry, sage, mint, grapevines and angelica root. I also visited the Chumash baskets stewarded at these two museums.

The Chumash baskets at the British Museum were collected from, and likely made within, the California Franciscan Mission system (1769–1834) into which most Chumash were forcibly moved. Another important part of the project was to visit these Missions, which enabled me to experience the environment and spatial layouts of the Missions and gave me a better contextual understanding. These were Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa (est. 1772), Mission San Buenaventura (est. 1782), Mission Santa Barbara (est. 1786), Mission La Purisima (est. 1787), and Mission Santa Ines/Ynez (est. 1804).

While I was in the Santa Ynez valley visiting Mission Santa Ynez, I also visited the new Santa Ynez Chumash Museum and Cultural Center and met with colleagues there. I also conducted archival research at the Santa Barbara Mission Archives to explore whether it might be possible to identify the makers of the baskets by examining specific Mission records and registries, an element of the project that will need further investigation.

The homecoming of the basketry hat

Rose: In January 2024, the Chumash basketry hat travelled to Los Angeles. This was timely as 2024 marked 200 years since the 1824 Chumash revolt against the Spanish and also coincided with the exhibition at the Autry Museum. The somelelu's homecoming for the exhibition was incredibly significant.

Tima: There's a sacred magnetism that drew the somelelu back to our community – like salmon returning to birth waters. And we stood with her, admiring her as teacher, not as an artefact. Her presence reminded us that what belongs together cannot be forever separated – not by oceans, not by years, not by the painful erosion of our culture. The somelelu's presence during this anniversary is no accident but rather the universe's poetry, its way of saying: 'Look here at what endures. Look here at what cannot be lost when memory and love keep a faithful vigil.'

Rose: Our Assistant Collection Manager Cynthia McGowan carefully and expertly packed the somelelu into her crate to continue her rest over the Atlantic before being reawakened by the warm Pacific air of the West Coast and her relatives waiting to greet her. It was a powerfully emotive feeling watching her at 5am in a Heathrow cargo shed getting ready to fly, knowing how significant this cultural belonging is and how excited people in Los Angeles were to see and be near her.

Once we arrived in LA we were taken to the Autry Museum of the American West and then had to patiently wait out the standard acclimatisation period before we could open her crate. When she was brought out the Chumash co-curator of the exhibition, Dr Deana Dartt, and other community members sang to her. Colleagues from the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles also joined us and were there to take a 3D scan of the somelelu which could then be accessed by the community.

Tima: When the somelelu emerged from the crate, it wasn't simply an artefact being unveiled – this was a relative returning home after a long absence.

Singing to her was a reminder of how precious and deeply missed she had been, a gentle way of saying, 'We remember you. We have been waiting for you. You belong here among your people.' The songs acknowledge that this basket carries spirit and story, deserving the respect and celebration we would offer any family member finding their way back home after two centuries away.

Rose: Considering the significance of the somelelu, it was incredibly important that members of the Chumash community could have the opportunity to welcome and spend time with her before being separated by glass. As Dr Deana Dartt put it in the email invite, 'If you haven't been home in about 300 years imagine there being none of your relatives to greet you' and 'She has been gone a long time, let's sing her back home'. The Welcoming Ceremony took place on the morning of 26 January 2024 in the gallery, attended by around 20 Chumash and other selected people. They spoke, sang and prayed to her and closely observed how she was made.

Being part of this experience was exceptionally moving. Most of the discussion revolved around not just the somelelu as a tangible hat, but around the woman who made her. What would her life have been like in the Mission system? What were her motivations when weaving the hat? How long might it have taken her? Did she have her children with her at the time and was she teaching them material and ecological cultural knowledge as she wove? Was she was a relation of any of the women welcoming her now?

By midday the glass was closed, and she joined her 'sisters' in a display of other women's basketry hats. The afternoon continued with a 'weave-in', a communal few hours of basketry weaving and further discussion. The following day was the official exhibition opening and this event began with a panel talk called Recontextualising Native Basketry: From Coastal California, to London and Back in the Autry Museum's theatre, in which I had the pleasure of joining Tima, as well as Dr Deana Dartt and Kelley Stewart (Tongva weaver and scholar) as panellists.

The research trips in December 2023 and January 2024 were incredible experiences. The value of learning from Indigenous community members, being physically present in the areas where the collections we steward are from and learning about them within their context is undeniable.

Tima: Seeing the somelelu in person and welcoming her to the Autry Museum and back home to Southern California, I was so overwhelmed! Because I'm a weaver, a basket like the somelelu is a link back to a single person, a woman like me, whose fingers and mind were mirrors of mine – feeling, touching, creating, imagining. I feel connected to her through this basket – it wipes away 250 years of time.

Continuing Chumash cultural practices

Rose: During the January visit, I also had a wonderful afternoon with Tima in her garden which is teeming with plant materials used for her basketry. Over the course of several hours in the warm January sun, she explained how she tends to and harvests plants such as juncus, sedge and sumac, and demonstrated how to prepare dyes, such as mixing water, oak galls, walnut hulls and railroad ties in rusty pots.

Tima: The challenges we have in continuing our cultural practices are overwhelming: getting access to the places our plants grow, pollution of the ground (weavers process the polluted plants in our mouths), extinction of the plants themselves (invasive species, urban sprawl, water shortages), and keeping the interest going of tribal members in a world of modern distractions.

Future collaboration

Rose: The experience in California was significant and emotional, but the project wasn't over yet. Tima and I arranged for a group to travel to the British Museum between 28 April and 2 May 2024. Tima was joined by fellow Chumash weavers and cultural educators, Cristina Gonzalez, Julia Cordero-Lamb, Alicia Cordero and Patricia Gonzales. The majority of the visit was spent at the collections site in East London, working with the Chumash cultural belongings. This included cooking and fishing instruments and various other bone and stone tools, flints, pipes, shell jewellery, a tomol (Chumash canoe) paddle and, of course, the Chumash basketry collection. Their visit ended with a captivating presentation to British Museum staff about Chumash material culture and Chumash experiences today.

Tima: The baskets felt deep asleep when we arrived… snoozing in their trays and boxes. We brought songs and laughter and touches and we hope it woke them up – feeling like they were surrounded by home and family. We consider baskets and other objects to be our relatives, so visiting them in the British Museum collection was a way for us to reunite as a family: remind them they're not forgotten, sing to them, be in community together, and give them back their real names in our language. Being able to bring our knowledge in order to change 'basket made of vegetable fibre' to ''axtapši'li (cooking basket) made of syit, taš, šwoštolk’oy, and šu'nay' is so incredibly healing for both us and the baskets.

Rose: Following the group's visit, Tima has been creating an incredible dataset of Šmuwič Chumash language terms for the names, uses, and materials of the Chumash collections, along with other cultural knowledge. I have used this to update the collection records, ensuring that this valuable knowledge is reflected and that the Chumash language is included in the database. You can see this for example in the record for the basket Tima has just mentioned. The project was further augmented when Abe Sanchez, who had organised the ethnobotanical workshops in California, visited the British Museum in October 2024 with Dr Theresa Ambo (Tongva). Over several days they spent time with the basketry collection from Southern California, sharing additional ethnobotanical knowledge about the Chumash basketry and, significantly, attributing tribal affiliations to another eight California baskets previously labelled as 'Mission Indian', giving them back their identity. All of this work marks a crucial step toward centring Indigenous knowledge in museum collections and their documentation, making it easier for communities of origin to locate and learn more about their cultural belongings.

Tima: As for what's next for this collaboration, I'd like to see future visits with the British Museum; engaging in conversations and dreaming up collaborations on how to exhibit the collections so that visitors can have a richer experience through our cultural lens. On a broader scale, our cultural items aren't just at the British Museum – they are also scattered across dozens of museums across the European continent. I dream about visiting all the museums and finding ways to connect the collections, learn from them, improve them, and bring their stories into full colour for visitors.