Read about these discoveries and many more in the new book Beneath our feet: everyday discoveries reshaping history.

From a glittering pendant bearing the emblems of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon to a flint handaxe used by the earliest humans, these extraordinary finds – found in ordinary places by members of the public – have changed the course of history.

Whether found by accident or by dedicated detectorists, in a potato field or on the beach, they prove that there's so much to discover buried right beneath our feet.

The Happisburgh handaxe

The Stone Age flint that changed everything we knew about the first humans in northern Europe.

In 2000, Mike Chambers was walking his dog on his local beach in Happisburgh (pronounced 'Haze-bruh'), Norfolk, when he saw the glossy black flint of what turned out to be a Stone Age handaxe. The carefully crafted flint tool, now known as the Happisburgh handaxe, is over 500,000 years old and in incredible condition for its age. It would have been used 'unhafted' (without a handle) and had sharp edges that were ideal for cutting meat or even harder materials like wood.

Although other flint tools had washed up previously, this handaxe was found in situ, embedded within ancient sediments that had been exposed by the low tide. Thankfully Mike realised that the object was a significant find and reported it to Norwich Castle Museum, which arranged for archaeologists Nigel Larkin and Peter Robins to visit the site and record important information about the context. Nick Ashton, curator of Paleolithic collections at the British Museum and one of the leaders of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain project, said that Mike's find 'led to a decade of fieldwork with remarkable results'. In the years that followed, excavations revealed that Happisburgh's windswept sandy beaches were of great archaeological interest, providing the earliest evidence of human occupation anywhere in Britain.

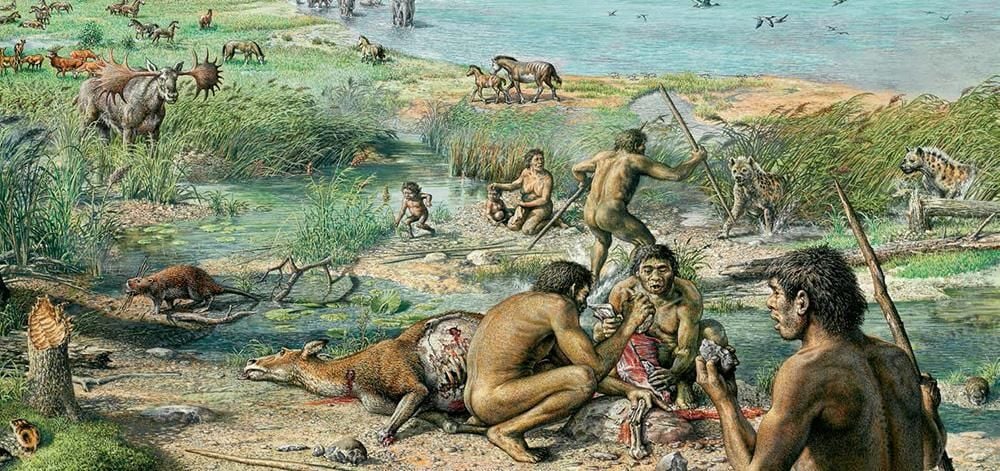

In 2013 the team made an 'extraordinarily rare' discovery: a collection of ancient footprints embedded in the fast-eroding sediment. Some of the prints clearly belonged to children, while the most distinct was made by a man about 1.7 metres tall. They are the oldest human footprints known outside Africa, dating to over 850,000 years ago, from a period known as the Lower Paleolithic. The people who made them were not Homo sapiens like us, but Homo antecessor, a species that preceded Neanderthals in Europe. They walked upright and were of a similar height to modern humans, with a slightly different facial appearance and smaller brains. These people lived in Happisburgh before the English Channel had formed for the first time (about 450,000 years ago) when Britain was physically joined to what would become modern-day France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The footprints were preserved in estuary mud of the River Thames, which flowed much further north than its present course. Archaeologists have suggested that the 'family' represented by these footprints could have been searching for seafood in the mudflats along the river edge. These people were using flint tools but, so far as we know, not fire. This in itself is remarkable, since the climate of eastern England at that time was like that of southern Scandinavia today, with long, cold winters. The estuary was dominated by open grassland with pine forest on the hills beyond, and inhabited by mammoths, bison and sabre-toothed cats.

Mike's discovery of the Happisburgh handaxe ultimately not only led, Nick notes, to the discovery of these remarkable human footprints, but also 'pushed back the known occupation of northern Europe from 500,000 to over 850,000 years ago. It has forced us to reconsider how humans coped with the long, cold winters without the use of fires and prompts questions about their abilities to make clothes and build shelters.'

Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon necklace

The treasure find of a lifetime for a newcomer to metal detecting.

Charlie Clarke, a café owner from Birmingham, had been detecting for only six months when he unearthed an enamelled gold pendant necklace bearing the initials 'H' and 'K' from the site of a dried-up pond in north Warwickshire. He had made the discovery of a lifetime. Recognising the pendant's significance, Charlie says he 'shrieked like a schoolgirl' when he first set eyes on it. Charlie immediately contacted his local Finds Liaison Officer (FLO), Teresa Gilmore, who quickly arranged to collect the pendant and bring it to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery for safekeeping. As Teresa recalls, 'I had a mental checklist on my way down to meet with Charlie. If the item was Tudor as he described, then it needed to be gold and with enamel on it. Which it had.' Closer inspection by Teresa confirmed that this was no ordinary Tudor find. 'I noticed the initials H and K – especially the H, in lower case and a Lombardic script. And then the royal symbols – Tudor rose and pomegranate. All those factors combined made it quite important and not just a piece of Tudor goldwork.'

Stunned by the pendant's large size and relatively good state of preservation, Teresa knew that there would be intense interest in its discovery. She contacted the subject specialist at the British Museum and colleagues at Historic England, who subsequently undertook an excavation of the findspot. Charlie was thrilled that archaeologists were so interested in his discovery. The pendant was photographed by Teresa's colleagues in Birmingham before being transported to the British Museum just before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The timing could not have been worse. Subsequent national lockdowns and furloughing of staff, followed by the long, cautious road back to in-person work as the pandemic receded, meant that further investigation of the artefact took several years. Eventually, however, the pendant was scrutinised by British Museum scientists and conservators in one of the widest collaborative assessments of any Treasure find. Relevant experts were invited to view the pendant and contribute their thoughts about its manufacture, purpose and ownership, to understand the find properly and so that the report would be as well-informed as possible.

The jewel that Charlie discovered is believed to be associated with Henry VIII (r. 1509–47) and his first wife Katherine of Aragon (1485–1536). Although their marriage – from 1509 until it was annulled in 1533 – is famous for its acrimonious ending, it was the longest of Henry's six marriages by some margin. The pendant is actually made of three objects: a gold chain of 75 links, a clasp in the form of an enamelled gold hand, and a gold heart-shaped pendant with enamelled decoration. The front features the intertwined branches of a bush, the left half of which bears a Tudor rose with red and white enamelled petals (the symbol of Henry's dynasty) and the right half a pomegranate (representing the heraldic arms of Katherine and the Spanish kings of Aragon). Combined rose and pomegranate motifs were worn by loyal subjects on badges to show their allegiance to Henry VIII and Katherine during their marriage. Across the bottom of this design is a banner with red-enamelled text reading 'TOVS IORS', possibly a pun on the French word toujours ('always'), with spacing that makes it sound like 'tous (all) yours' when read aloud. The back has the red-enamelled Lombardic letters 'H' and 'K' (Henry and Katherine), and the same motto in black enamel. Above the hand-shaped clasp, a cloud shape gives the appearance of a hand coming down from the heavens. This was a common 16th-century emblem representing the divine hand of God, and which occasionally also symbolised romantic love when combined with a heart. Several historical documents from the 1510s and early 1520s describe a similar motif on royal horse trappings at public events. British Museum scientists analysed the metal and enamels in various places of the jewel and found them to be consistent with materials from the early 16th century. This reinforces the possibility that the piece was constructed during the period of Henry and Katherine's long but unhappy marriage.

The pendant is one of the finest and most important post-medieval finds discovered by a detectorist and reported under the Treasure Act. Surviving examples of early Tudor jewellery in public collections are quite rare; indeed, it was the absence of direct parallels for close comparison that made it necessary for specialists to scrutinise this find so closely.

According to Rachel King, Curator of European Renaissance and Waddesdon Bequest at the British Museum, previously it had only been possible to read about the jewels to which the wealthy then had access, but now, 'Thanks to Charlie's find, we can actually hold this history in our hands for the very first time.'

Despite its monogram and decoration associated with Henry and Katherine, the pendant was probably not made as a gift from one to the other. It doesn't feature in the known inventories of royal jewels from the early 16th century. Although they appear large and impressive to 21st-century eyes, the pendant and chain lack the finesse in places that one might expect of a royal recipient. But the items obviously belonged to someone of high standing; laws from the early 16th century indicate that a chain of the weight and purity here would not have been suitable to be worn by anyone of lesser rank than the son of a baron. This jewel probably has some relationship to life at court. Perhaps it was created to be worn by a high-ranking guest at an event, or as a gift or prize for a participant.

It's not yet certain whether the pendant will end up in a public collection but wherever it finds a home, it is sure to impress visitors, taking them back to a time in England's history that has left an indelible mark on the national consciousness.

The Ringlemere cup

A 4,000-year-old golden goblet found in a potato field.

Retired electrician Cliff Bradshaw was 'looking for Anglo-Saxons' when he instead discovered one of the most important Bronze Age treasures ever found in Britain. In November 2001 Cliff was metal detecting on a 'friend's permission' (a site obtained by a detecting partner) in potato fields at Ringlemere Farm in Woodnesborough, Kent, concentrating on an area of higher ground that he hoped might be the site of an Anglo-Saxon settlement. This was a reasonable assumption, since he had found early medieval artefacts there on previous outings. He came across a strange metal object that he initially thought was a shiny brass Victorian light-fitting. The item was clearly damaged – it had taken an enormous whack, most likely from a plough, resulting in a large dent. He decided to take it home and check it out properly.

Once the find had been cleaned, Cliff got out his history books and realised, to his astonishment, that it looked just like the Rillaton Cup, a gold vessel recovered in 1837 from a stone cist beneath a cairn on Bodmin Moor, Cornwall – and (so tradition says) later used by George V to store his collar studs at Buckingham Palace. Cliff immediately contacted various experts in Kent, including local archaeologist Keith Parfitt, and reported the cup as potential Treasure to his Finds Liaison Officer (FLO), Michael Lewis (one of the co-authors of this blog). Cliff showed Michael several other objects before he revealed the cup, which he had safely stored in an ice-cream container. Michael was bowled over by the precious metal vessel, especially the quality of its craftsmanship. The verdict was swift and unanimous: Cliff was right! He had found the Ringlemere Cup, a finely made gold Bronze Age vessel for which the only known English parallel is the Rillaton Cup itself.

The Ringlemere Cup (now on display in Room 51) dates to 1950–1750 BC, in the Early Bronze Age, so it is almost 4,000 years old. The body of the cup has been created by carefully hammering a single piece of gold. It has distinctive corrugated sides and a handle, made from a single metal strip and embellished with ridges that match those on the vessel's sides. It has a flared rim and cone-shaped body tapering to a rounded base, which means that the cup cannot stand alone without support, suggesting that it had a specific (perhaps ritual) purpose. The cup's thin gold conducts heat well, which might have made handling and drinking from the Ringlemere Cup an especially sensual experience, tying in with the hypothesis that it had a ritual function. Although it is unknown what type of liquid the cup held, it is possible to imagine that the vessel could have been passed around a gathering and drunk from by each person in turn, like a communion cup in Christian worship 2,000 years later.

A small number of similar so-called 'precious cups', with unstable bases and usually with handles, are known from north-west Bronze Age Europe. There are examples made in silver, and some of similar form in amber and shale. Other gold cups have been found in France, Germany, Switzerland and northern Italy, but the only two from Britain are the Ringlemere and Rillaton examples. Not only had Cliff found an object of national and even international importance, but an entire site equally so. Keith Parfitt, the local archaeologist who led the excavations at Ringlemere Farm said that 'although the gold cup was a spectacular find in its own right, it also led to the identification of a previously unknown prehistoric ritual landscape, as well as an exceptionally early Anglo-Saxon cemetery, all of which combine to make this a crucial new site for the archaeology of Kent.' So Cliff had been right in looking for an Anglo-Saxon site at Ringlemere, but it was only one part of a complex and intriguing landscape that had been occupied for thousands of years.

Conclusion

Beneath our feet is another world, hidden from view, waiting to be discovered. It is a world of the past, where the objects left behind give clues about those who were here before us – who they were, and what their lives might have been like. Some of the most spectacular artefacts discovered in Britain have been found by members of the public rather than professional archaeologists, most through metal detecting. Detectorists may hope to make the find of a lifetime, but most get just as excited by common items such as worn tokens and broken buckles, thrilled to be the first person to hold the object since it was lost or buried. The excitement in this kind of discovery, besides the thrill of finding things, is that it connects people who have a recreational interest in the past with archaeologists who study it for a living. Even common items provide important evidence about the past, so it is crucial that detectorists and other public finders exploring past landscapes do so responsibly and record their finds. When public finders and archaeologists work together, we can learn more about the past, ensuring that the most important objects end up in museums for everyone to see, and that others are recorded so they can help all of us to understand the archaeology and history of Britain.

Beneath our feet: everyday discoveries reshaping history is out now! Grab your copy today to read more about these incredible discoveries and dozens more.

If you find something you think could be treasure, report it to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS).