Trail information

Suitable for all ages

Duration

Around 30 minutes

Follow the iconic and revealing story of the boy king Tutankhamun at the British Museum.

Tutankhamun's reign as an Egyptian pharaoh lasted around nine years (about 1336–1327 BC), but his legacy continues to shine centuries later. The 1922 discovery of his tomb in Egypt brought his story to the world. Much was learnt from the nearly intact tomb, which included thousands of objects.

Trace Tutankhamun's period through objects at the British Museum: come face-to-face with a statue of the young king, the figure of the man who claimed the throne after him, and an inscription showing how his reign was officially deleted from history.

The trail focuses on a small number of objects in Room 4: Egyptian sculpture.

Follow the trail below and use the map to explore the seven locations.

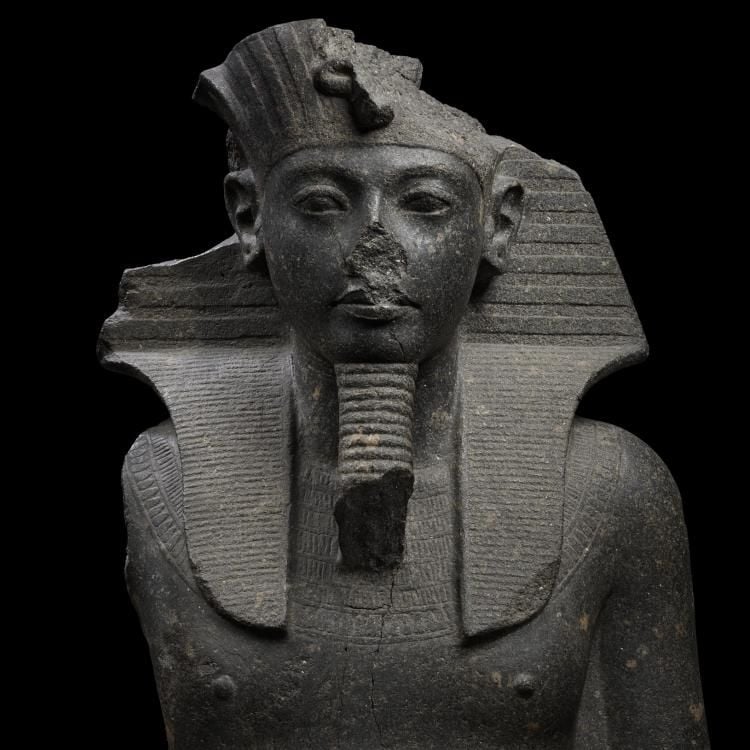

Statue of Amenhotep III

1. Statue of Amenhotep III (Room 4)

The reign of Tutankhamun's grandfather Amenhotep III (around 1390–1352 BC) marked the peak of ancient Egypt's prosperity and reflected long-held traditions of kingship and religious belief. His name incorporates that of Amun, one of the most powerful deities of the time.

Amenhotep's reign was marked by a strong government and stable society, supported by enormous wealth from Egypt's empire – especially gold from Nubia. The king ordered huge temples to be built, provided with finely-sculpted statues of himself and the gods.

This statue is a conventional representation of an Egyptian king, conveying his supreme status as head of state and of the religious hierarchy. In this granodiorite statue, Amenhotep III is shown wearing a nemes head-dress, which was in reality made from a piece of cloth. The uraeus (a rearing cobra, an ancient Egyptian symbol for royalty and authority) on his forehead protected him, while the bull's tail, finely carved between his legs, conveyed strength.

Lion with a Tutankhamun inscription

2. Lion with a Tutankhamun inscription (Room 4)

This lion statue was set up in a temple erected by Amenhotep III in Nubia, and reflects the extent of the pharaoh's authority, which was recognised in Sudan as well as in Syria-Palestine and the eastern Mediterranean.

When Tutankhamun became king (around 1336 BC) he added an inscription to the lion recording his descent from Amenhotep, illustrating the importance of dynastic succession to the ancient Egyptians.

Please note this object is currently part of a touring exhibition and will not be on display until late 2024.

A list of Egyptian kings

3. A list of Egyptian kings (Room 4)

This inscription was set up by Ramesses II in a temple at Abydos about fifty years after Tutankhamun's death. It originally recorded the names of earlier kings of Egypt, whom Ramesses regarded as 'legitimate' predecessors whose memory deserved honour. Amenhotep III is named there, but the list omits the next four rulers – including Tutankhamun – and jumps straight to Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the dynasty. This shows that Tutankhamun had been discredited soon after his lifetime and had been struck from the official record.

Stela of Akhenaten

4. Stela of Akhenaten (Room 4)

This image shows King Akhenaten, the son of Amenhotep III. Along with Tutankhamun, he was one of the four rulers omitted from the King-list.

Akhenaten believed in only one god, the shining disc of the sun, which was called the Aten. He ordered the temples of Egypt's old gods, including Amun, to be closed. Akhenaten built a new city for himself (Akhetaten, now known as el-Amarna), where he and his wife Nefertiti worshipped the Aten. The formality of earlier Egyptian art was relaxed and the king was depicted in an unconventional style. Tutankhamun is usually thought to have been Akhenaten's son. He was at first called Tutankhaten and he was probably born and grew up at Akhetaten.

Akhenaten's drastic religious changes offended the establishment, and after his death he became a hated figure. His city was abandoned and the monuments he had made in honour of the Aten were destroyed.

Statue of Tutankhamun

5. Statue of Tutankhamun (Room 4)

Tutankhamun became king when he was around nine years old. His reign did not last long, as analysis of his mummy suggests that he was around 19 when he died. While his cause of death is unknown, it has been suggested it was the result of injuries, perhaps from a chariot accident, or from an infectious or congenital illness. When the young king died unexpectedly, he was buried in the Valley of the Kings in what was probably not intended as a king's tomb.

In this statue, Tutankhamun is represented in traditional style with a head-dress known as a nemes, a beard and a broad collar. He is shown making an offering to the traditional gods of Egypt – a sign that in his reign the old religion and royal imagery were restored. His predecessor Akhenaten had revolutionised the religious and artistic traditions, introducing the worship of a single god: the sun disc Aten. Tutankhamun and his contemporaries quickly reversed the unpopular changes made by Akhenaten. However, as Tutankhamun was Akhenaten's son and had grown up under his authority, he was regarded as tainted by association.

As seen in object three, Tutankhamun's name was omitted from king-lists and this statue was usurped (reused) by King Horemheb a few years after Tutankhamun's death. Horemheb added an inscription and his name on the back of the sculpture. We know the statue was made for Tutankhamun, however, because the facial features are those of the official royal images of him, as seen on other sculptures and objects from his tomb.

Statue of Horemheb and his wife

6. Statue of Horemheb and his wife (Room 4)

King Horemheb (who usurped Tutankhamun's statue – object five) was not of royal birth. This limestone statue represents him before he became king, probably with his wife. He was the commander of the Egyptian army during Tutankhamun's reign and held the unusual title 'King's Deputy'. Such a powerful official was in a position to control events. Horemheb, together with the senior courtier Ay, were the most influential figures while the boy king ruled.

When Tutankhamun died childless, Ay and Horemheb seized the throne in succession. Ay reigned only briefly (around 1327–1323 BC), but under Horemheb (around 1323–1295 BC) the process of erasing Tutankhamun from history had already begun.

Tutankhamun today

Tutankhamun today

Due to his short reign, Tutankhamun didn't have a great impact on society during his lifetime. But this didn't prevent him from becoming one of the most well-known ancient Egyptian kings, a poster boy for pharaonic times.

Soon after the discovery of his tomb in 1922, his image started to be reproduced in many contexts. He was the first pharaoh to appear on Egyptian currency, with the reproduction of one of his statues on banknotes first issued in 1930. From state-produced currency to artefacts of daily life, such as children's books and sweet tins, the new discovery put Tutankhamun – and anything linked to him – in the spotlight.

This trail was developed in partnership with the British Museum International Training Programme to commemorate the centenary of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb.

The discovery of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered in November 1922 by archaeologist Howard Carter and a team of local Egyptians, including four foremen: Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed. They worked together with a team of experts from Britain and the USA to preserve and document the objects.

The discovery was an important archaeological event. Tutankhamun's tomb is the only pharaoh's tomb dating from Egypt's New Kingdom (around 1550–1069 BC) to have been found substantially intact. The contents provide an unequalled insight into royal funerary practices, art and craftsmanship of the period.

The discovery was a sensation that created huge interest in Egyptology and the story of the boy king. Reporting on the event, the Times described one object, Tutankhamun's throne, as: 'probably one of the most beautiful objects of art ever discovered.'

The burial site was situated in the Valley of the Kings, located on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes. It was used as the burial place for the kings of the New Kingdom.

All of the items found inside Tutankhamun's tomb were displayed in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and the Luxor Museum, but will be newly exhibited in the Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza. Carter's excavation records are kept in the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

'The Treasures of Tutankhamun'

Running from 30 March to 30 December 1972, The Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition is the most popular in the Museum's history.

Opened by Queen Elizabeth II, the exhibition coincided with the 50th anniversary of the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb. Over 1.6 million visitors came to see the objects on loan from Egypt.

In total, 50 objects were exhibited in The Treasures of Tutankhamun, one for every year since the discovery of the tomb. The star object was the famous gold mask from the head of the king's mummy.

The objects were carefully assessed in Cairo before being packed in airfreight crates and flown to England. The gold mask, together with the other objects of the highest value, travelled in a special high-security consignment on board a Royal Air Force plane.

The public reaction to the exhibition was overwhelming. Originally scheduled to run for six months, the exhibition was extended until 30 December 1972 because of its popularity. It was open six and a half days per week, 10.00–21.00.

A total of 1,694,117 visitors saw the objects, over 7,000 per day. Every day, long queues of visitors stretched from the first-floor galleries, where the exhibition was staged, back through the Museum, around the forecourt and colonnade and out onto the pavements. The profits from the exhibition were donated to major cultural projects in Egypt.