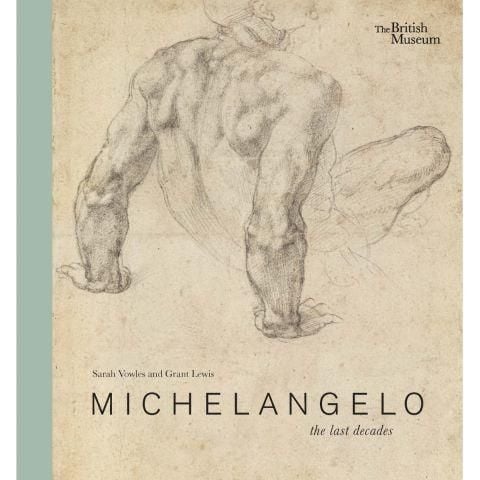

View some of the works in this story in the special exhibition Michelangelo: the last decades (until 28 July 2024).

From the Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican to the soaring double-shelled dome of St Peter's Basilica, some of Michelangelo's most dramatic and innovative works are, essentially, beautiful works of propaganda.

These magnificent commissions, produced in the final 30 years of Michelangelo's life, were designed to impress viewers by reflecting the grandeur, stability and permanence of the Catholic Church. But the very fact that the Church needed to emphasise its power hints at the tumultuous changes witnessed in the 1540s, as reforming ideas continued to send shockwaves through the Church. Michelangelo, who relied on Papal patrons and whose friends included members of the reformist spirituali, found himself making art on a knife edge between faith and heresy.

Rome and the Reformation

Michelangelo and his contemporaries lived at a time of intense uncertainty. Part of that was down to politics and territory: the Italian peninsula had become a shifting patchwork of states, with the armies of the King of France and the Holy Roman Emperor helping to reshape boundaries and change overlords. But politics in the Renaissance blurred into religion – and vice versa. Reformist movements inspired by the arguments of Protestant theologians Martin Luther (1483–1546) of Germany and John Calvin (1509–64) of France had begun to win over adherents in Northern Europe, challenging ideas at the very heart of Catholicism and offering an alternative path of faith to those who were disillusioned by tales of corruption and avarice in the Catholic Church.

This spiritual incursion into the Church's territory was followed by a cataclysmic physical incursion: the 1527 Sack of Rome. The troops of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V – whose territories included Spain, Germany, Austria and Burgundy, and who had further ambitions in southern Italy – had been stationed outside the city, in the hope of intimidating Pope Clement VII (1478–1534) into supporting the emperor's political claims. Disaffected and unpaid, the troops – who included large numbers of German Protestants – took matters into their own hands and stormed the city, looting, pillaging and murdering, while the Pope took refuge in the fortress of Castel Sant' Angelo. They took power and Rome was still reeling when Michelangelo returned from Florence less than a decade later, in 1534 – the point at which our special exhibition Michelangelo: the last decades begins.

One of the key areas of Renaissance religious debate in the years around 1540 was the nature of salvation. Protestant theologians argued that Scripture (the sacred writing of Christianity brought together in the Bible) was the only true guide for salvation: an individual's salvation relied not on the institutions and intercession of the Catholic Church, but on the individual themselves. This presented an overt challenge to the authority of the Church.

By faith alone

For some Protestant groups such as Calvinists, this shift to the individual was explained through the doctrine of predestination, which held that some people were automatically destined for heaven. Other times it took the form of the argument for sola fide ('justification by faith alone'). This idea derived ultimately from the Epistle to the Ephesians, in which St Paul reassured his listeners that salvation did not depend on their own actions but had been assured by Christ's sacrifice: 'For by grace are ye saved through faith, and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God' (Ephesians 2:8). In the teachings of the Catholic Church, faith in God's grace had to be supplemented by good works, including acts of charity, confession and participation in the sacraments of the Church, which built up spiritual credit for salvation. These beliefs were challenged by early reformers, who argued that good works were incidental to salvation. They did not disregard good works, but believed they should be prompted by a Christian love for one's neighbour, rather than to curry favour with God. They believed that to suggest otherwise, as the Church did, was to imply that God's mercy was contractual. An individual's faith in God's grace was, 'by faith alone', sufficient for salvation.

Although justification sola fide became increasingly associated with Protestant movements, particularly Lutheranism and Calvinism, it was, in the 1530s and early 1540s, embraced by a broader range of reform movements, especially those with a more mystical and visionary bent. There was considerable appetite within Italy for a renewal of the Church, which was felt to have become mired in luxury and avarice, and reformist zeal could easily sit alongside respect for the central institutions of papacy and Church – even if their incumbents were criticised. For many, the Sack of Rome in 1527 was proof of divine retribution against the corruption at the heart of the Catholic establishment: a kind of almost-apocalyptic reckoning. By the time Michelangelo returned to Rome in 1534 after the death of Pope Clement VII, the need for reform had become widely acknowledged, even within the Vatican itself. However, people disagreed on how that could be achieved.

Common ground

In the late 1530s, Pope Paul III (1468–1549) took the first steps to define the Catholic Church's response to the transalpine reformers. Despite embodying many of the faults with which the Lutherans took issue – he had at least four children, whose careers he promoted assiduously – he was moderate and conciliatory. He duly instituted an investigative commission, whose members included not only the English Cardinal Reginald Pole, who hoped to find common ground with the Protestant reformers, but also Cardinal Giovanni Pietro Carafa (1476–1559), later Pope Paul IV, who believed that reform could be achieved only by rooting out all traces of heresy and weakness within the ranks of the Church. While the next few years would lead these men in very different philosophical directions, they were, for the moment at least, united in the hope of finding solutions to the Church's problems.

Reginald Pole (1500–1558) was the second cousin of Henry VIII, and had left England after refusing to accept the King's divorce from Katherine of Aragon and the consequent Act of Supremacy – a decision he had defended at length in the 1536 treatise Defence of the unity of the Church. Pope Paul III appointed him a cardinal in December 1536, and Pole thereafter allied himself energetically with the question of Catholic reform. His moderate beliefs attracted a circle of like-minded friends in Rome, known as the spirituali, who shared a vision of Catholicism that could engage in mutually beneficial dialogue with Lutheran reformers. It must be remembered that, until probably the early 1550s, this was not considered heretical, although it was increasingly considered to be unwise, irresponsible and problematic.

A turning point seems to have been the liberal Cardinal Contarini's efforts to find common ground with Lutheran representatives at a council of 1541 in Regensburg, which was optimistically intended to reconcile the different beliefs within the Holy Roman Emperor's domains. The final proposition was an agreement that salvation could be reached either through faith alone, or through good works, an accommodation that ultimately drew vociferous criticism from both Lutherans and Catholics, none of whom felt able to admit this kind of laxity on issues that were at the very heart of their respective beliefs. Pole would later face similar issues at the Council of Trent (a pivotal interdenominational council held from 1545–63), where he realised that it would not be possible to reach an agreement within the Catholic Church that embraced the concept of sola fide.

Timeline: 1521–1536

1521

Martin Luther is excommunicated

1527

The Sack of Rome

1533

Henry VIII divorces Katherine of Aragon

1534

The Act of Supremacy: Henry VIII breaks with Rome

1534

Michelangelo returns to Rome

1536

Reginald Pole is made Cardinal

The 'spirituali'

Yet the die had not yet been decisively cast. It is crucial to remember that, when Pope Paul III died in November 1549, Pole was one of the two leading candidates to replace him, and that he lost the contest by only a handful of votes – largely thanks to the machinations of Cardinal Carafa, who felt that Pole was little better than a heretic. But Pole clearly had considerable support within the College of Cardinals, even at this time; it was only when he failed to gain the required votes that he, and the Church more widely, seems to have accepted that the game was up. After the election of Cardinal Carafa as Pope Paul IV in 1555, the boundaries between faith and heresy hardened even further. The Roman Inquisition (established in 1542 to combat Protestantism) began to investigate members of the spirituali movement, whose openness to Protestant ideas was now deemed suspect.

The swift pace of religious change at this time can be seen in the story of a particular text that was popular among the spirituali: a devotional guide titled the Beneficio di Cristo ('Treatise on the Benefit of Christ's Death'). Originally written by the Benedictine monk Benedetto da Mantova, it encouraged readers to meditate on the image of Christ's Crucifixion not as a tragedy but as a triumph: the ultimate sacrifice which assured the salvation of humankind. This mystical interpretation of the Crucifixion made salvation more accessible, in that it didn't require good works or the mediation of the Church. The book was published in 1543 in an edition prepared by Marcantonio Flaminio, another member of the spirituali circle. His additions were provocative: now this controversial evocation of the Crucifixion was accompanied by arguments in favour of sola fide – the most extreme form of justification by faith – and even hints about the Calvinist doctrine of predestination.

On publication, the book enjoyed immediate and widespread popularity: more than 40,000 copies were printed, which was unheard of at the time, in a variety of European languages. Its success, however, was brief. With the establishment of the Roman Inquisition in 1542, reactionary elements within the Church were closing ranks. Just six years after publication, in 1549 the Beneficio di Cristo was placed on the Index of Prohibited Books and copies were avidly hunted down. Ownership was increasingly considered a sign of heretical inclinations. Suppression was so complete that only one copy of the first edition is known to survive: a tiny octavo (books generally sized between six and nine inches) volume in the library of St John's College, Cambridge, which was left to the college as part of a bequest in 1744 and only rediscovered in the 19th century.

Vittoria Colonna

The spirituali are of particular interest to Michelangelo's story because he formed a strong and immensely influential friendship with one of their number: the aristocratic religious poet Vittoria Colonna (1492–1547), whom he met in the late 1530s. She was a member of one of Rome's most ancient and powerful families, and was widely admired for her intellect, her deep spiritual feeling, and the virtue of her lifestyle. In 1538 she became the first female poet to have a collection of her work published, in the form of a pirate edition printed in Parma, and her works went through a further 11 editions before her death in 1547. By the time Michelangelo met her, she was in her mid-forties and had been widowed for 10 years. Although she had initially made her name as a poet with a series of sonnets addressed to her late husband, her poetry increasingly came to focus on Christ as the object of her love and the steward of her soul. Her impassioned, visceral verse and the deep compassion of her religious writings in prose, seem to have impressed Michelangelo just as much as her formidable, uncompromising character.

At Christmas 1540, Vittoria sent Michelangelo an extraordinary present: a manuscript containing 103 of her spiritual sonnets. Written out by one of her scribes, the poems were arranged by Vittoria herself into a new sequence especially for Michelangelo, providing him with a poetic blueprint for the journey of the questioning soul towards God. He was powerfully impressed by the gift, but he understood Vittoria well enough to know that she did not expect a return present, in contrast to the usual conventions of Renaissance gift culture. Instead, Michelangelo wrote her a flattering letter, likening her present to the grace bestowed by God upon the true believer – a gift of such magnitude that reciprocation was neither expected nor, indeed, possible. He also drafted a sonnet alongside his letter as a token of his gratitude, which echoed and magnified the same sentiments.

Vittoria sent Michelangelo other gifts besides her poetry, which testify to the intimacy and warmth of their friendship. In summer 1543 she sent him a 'green glass', a visual aid designed to help soothe the eye strain he had developed while working in the dim light of the Vatican, and she also sent him a mule. There were new poems too – 40 of them – which Michelangelo had carefully bound into the back of the gift manuscript she had given him. But arguably the most striking products of this friendship were the artistic designs that Michelangelo conceived for Vittoria, most importantly the Christ on the Cross and the Pietà, both of which invited the kind of sustained and imaginative contemplation that was central to Vittoria's spiritual practice.

Timeline: 1542–1564

1542

The Roman Inquisition is established

1547

Vittoria Colonna dies

1549

The 'Beneficio di Cristo' is placed on the Index of Prohibited Books

1555

Cardinal Carafa becomes Pope Paul IV

1564

Michelangelo dies

Between orthodoxy and reform

Christ on the Cross seems to have been the earlier of the two designs Michelangelo made for Vittoria. It is striking because it shows Christ not as dead or dying but as a robust, living, powerful figure. In the spirit of reformist theology, Christ is shown in the act of redeeming the sins of humankind, triumphantly undaunted by death – even as his sacrifice is evoked by the blood running down the base of the Cross. The drawing is aesthetically striking as well as intellectually satisfying. Christ's body is rendered with soft touches of chalk, giving a stippled effect, but the finesse of the modelling is balanced with taut, fluid contours which imbue the figure with a sense of active energy. While the drawing is of exquisite quality, it has been reworked, perhaps in response to Vittoria's own suggestions, with two angels added over the shaded background beneath the crossbars, and a skull drawn in at the foot of the cross.

Vittoria wrote to Michelangelo after seeing the design for the first time, and her enthusiasm is palpable, even after 500 years. She told him that it had 'crucified every other picture in my memory', and that she had studied it carefully with a magnifying glass, a mirror and a lamp, in order to appreciate every aspect of its sophisticated imagery. The design swiftly became popular, and there are numerous painted adaptations by Michelangelo's collaborator Marcello Venusti (about 1512–79), who at this period developed a mutually beneficial business partnership with the perpetually overworked master. Venusti was given Michelangelo's drawn designs and transformed them into jewel-coloured paintings, often on a small scale so that they could be used as devotional images within the home.

A painting by Venusti at Campion Hall in Oxford is thought to be the earliest surviving version of the subject, and its ownership can be traced back to the family of Tommaso de' Cavalieri, Michelangelo's muse and close friend. This emphasises not only the fact that Michelangelo moved in a small social world, in which most people knew each other, but also shows that a design conceived to appeal to reformist sympathies could also become popular among orthodox Catholics.

The second of Michelangelo's designs for Vittoria was the Pietà, which was made at her request. Once again, it related directly to Vittoria's own spiritual writings. In 1539–42 she had composed a prose meditation titled the Pianto ('Lamentation'), in which she evoked the Virgin Mary's thoughts and emotions as she cradled the dead body of Christ after the Crucifixion. There are striking parallels between text and image. Michelangelo's Virgin is a monumental figure, towering over the limp body of Christ, and bracketing him between her knees in a way that reminds viewers of his incarnation and birth.

Michelangelo and Venusti Pieta

Once again, the design started life as a highly refined drawing, now in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, US, but it seems likely that, from the beginning, it was intended to end up as a painting by Venusti. A large picture of the Pietà, now in a private collection, may very well be the original version that was painted for Vittoria: recent restoration has revealed a signature, in precious silvered paint, which records both Michelangelo's and Venusti's names as co-creators of the design, and the painting can be traced back to the Colonna family. Again, however, the imagery had much broader appeal: as well as being appreciated by the spirituali, the design was used in orthodox settings. Numerous painted versions survive by Venusti and his assistants, and the composition was even translated into bronze plaquettes and rock crystal engravings, one of which (in the Victoria and Albert Museum) is beautifully mounted as a pax: an object used as part of the Roman Catholic mass.

The fact that Michelangelo's designs spoke to both reformist and orthodox groups is testament to the upheaval of the times in which he was working, when the lines between faith and heresy were still blurred.

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ Michelangelo Venusti Pieta

The Roman Inquisition

Within the space of little more than ten years, this elite, intellectual, and deeply spiritual group had found themselves on the wrong side of religious history.

Personal salvation

Vittoria died in February 1547, after a long period of ill health, and Michelangelo was profoundly affected by her loss. They had been friends for 10 years, which were full of spiritual and intellectual discussion, and he had come to regard her as a spiritual guide. While the poems that he wrote for her do not share the sensual fervour of those he gave to Tommaso de' Cavalieri, they nevertheless testify to a profound admiration and passionate, albeit platonic, attachment. Her death left him floundering. The profundity of his sense of loss is captured in the biography written by his assistant Ascanio Condivi in 1553, where he recalls Michelangelo's account of his final visit to Vittoria on her deathbed. 'I remember him saying that his greatest regret was that he did not kiss her forehead, or her cheek, but only her hand.'

Vittoria inspired Michelangelo to create works which had a powerful emotional heft, and her spiritual practices also had a lasting impact on him. In his eighties, when he came to contemplate his own mortality, and his own hopes for salvation, he did so through the act of drawing, making a sequence of deeply poignant Crucifixion scenes. Their creation gave him the chance to meditate on aspects of Christ's sacrifice, and broader questions of bereavement, grief and resurrection, just as Vittoria had done, by studying the Christ on the Cross he had made for her, some 20 years earlier.

After Vittoria's death, and in the last decade of Michelangelo's life, the lines between faith and heresy hardened. The election of Pope Paul IV in 1555 was a death blow for moderates: the spirituali – which involved people who identified with different points on the religious spectrum, from Marcantonio Flaminio, who may have had Calvinist leanings, to Vittoria, who was orthodox in the way she lived if not in the way she thought, and Pole, who at one point had come very close to being elected Pope – became shrouded in suspicion. Within the space of little more than 10 years this elite, intellectual and deeply spiritual group had found themselves on the wrong side of religious history. Michelangelo's public works and private meditations grappled with major theological questions, but his orthodoxy was never really called into question. His ability to create designs that appealed to both sides is testament to his skill. Today the religious art he produced in those heady days of debate and change continues to speak to people wherever they sit on the religious spectrum, of all faiths, or none.