See the exhibition

Ancient India: living traditions is open 22 May – 19 October 2025.

About this guide

This guide has been designed for visually impaired visitors. It contains all the exhibition text in large print.

Please let us know what you think about this page. Tell a member of staff or email [email protected]

A plain English guide taking you on a tour of the exhibition, looking at 10 objects is also available.

Foyer

Foyer:

Behind the scenes: working with community partners

Throughout this project, the Museum's curators and other members of staff have worked alongside UK-based practising Jains, Buddhists and Hindus.

The Community Advisory Panel helped shape many aspects of the exhibition. This included the design, the use of eco-friendly and vegan materials and the selection of contemporary sculptures in the final section. They also contributed to some of the labels and the choice of products in the shop.

The Hands on desk outside the foyer, the sensory trail and the films in the exhibition were developed collaboratively with many different community partners. Some helped us unlock stories about the devotional images and religious rituals through touch, smell and sound. Others shared their personal stories in filmed portraits showing the different ways people across the UK choose to worship.

They generously shared their personal insights and perspectives to help develop the exhibition.

The Community Advisory Panel

Samaroha Das

Indrani Datta

Tanvi Jain

Tilak Parekh

Arshna Sanghrajka

Mehool Sanghrajka

Shandip N. Shah

The Community Advisory Panel also included Puja-Arti Patel, Karen Yuen and Sujatha Meegama (not pictured).

Photography by Sushma Jansari, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Dhanyavad (Welcome)

World-renowned tabla player Dalbir Singh Rattan has composed this music welcoming visitors to the exhibition. He is accompanied by Dillon Henry on guitar.

Length: about 3 minutes on a loop

Introduction

Panel to left of exhibition entrance:

Ancient India

living traditions

Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism are major world religions that originated in ancient India, a vast area of separate empires, kingdoms and republics. This exhibition explores the devotional art of these three religions, which share many similarities. It focuses on the period 200 BC to AD 600 when these sacred images transformed from symbolic to human form, creating the depictions that are still venerated today.

Plinth:

Meet the Buddha

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of the Buddha, aiming to end suffering and the cycle of rebirth through the pursuit of enlightenment. Buddha means 'enlightened one' in Sanskrit. This sandstone sculpture shows him sitting on a throne flanked by lions, his hands in a teaching gesture. Buddhism emerged in northern India at the same time as Jainism, which also focuses on learning from enlightened teachers. There are similarities in the devotional art of these religions.

Uttar Pradesh, India, about AD 475

British Museum 1880.7

Excavated by Markham Kittoe (1808–1853), an officer in the East India Company army, and placed in the East India Company's India Museum, London. When the India Museum closed in 1879 some of its collection was transferred to the British Museum.

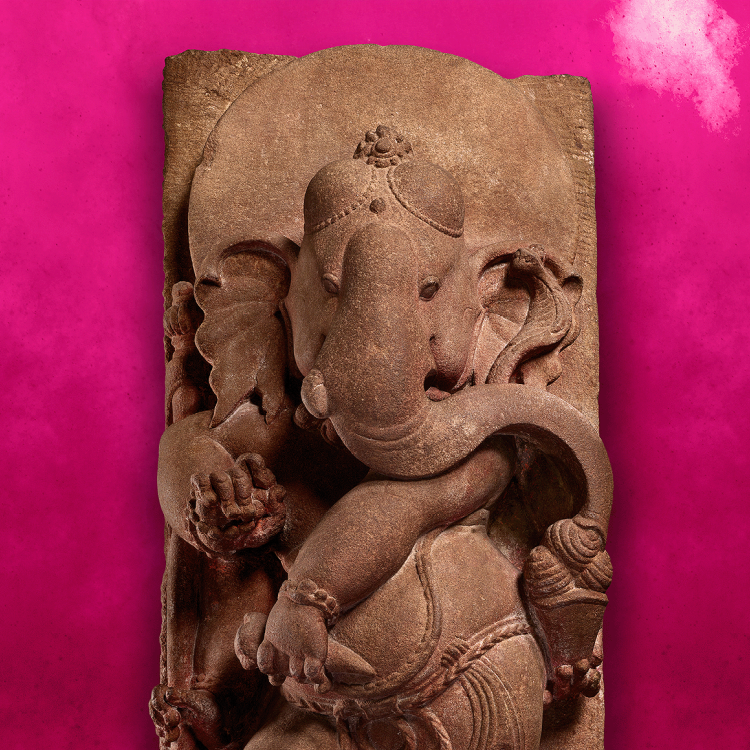

Meet Ganesha

Hinduism covers diverse beliefs, traditions and practices. Some gods, such as the elephant-headed Ganesha, are venerated by Hindus, as well as by some Buddhists and Jains. Ganesha means 'Lord of the ganas'. The ganas are the attendants of Ganesha's father, the god Shiva. This sandstone sculpture depicts a dancing Ganesha. He has a cobra tied around his torso, its head rising above his shoulder. The snake is a link to earlier nature spirits worshipped widely across ancient India.

Uttar Pradesh, India, about AD 750

British Museum 1974,0225.1

Purchased in 1974 from dealers Spink & Son Ltd. Funded by the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund, set up by P.T. Brooke Sewell (1878–1958), a merchant banker who created two funds for the British Museum to purchase artworks from Asia.

Meet a tirthankara

In Jainism, the path to enlightenment requires non-violence to all living things. This marble sculpture depicts a Jain enlightened teacher, who is human rather than divine. Seated in meditation, this tirthankara can be differentiated from an image of the Buddha by the sacred symbol of an endless knot in the middle of his chest. Tirthankara means 'forder of the stream', referring to the path to omniscience they create for others to follow.

Gujarat, India, 1150–1200

British Museum 1915,0515.1

Donated anonymously in 1915 in memory of Sir Alfred Comyn Lyall (1835–1911), a British civil servant in India, who was Foreign Secretary to the Government of India from 1878 until 1881.

Wall on the right:

Sounds and smells of life and worship in India

The audio in this exhibition includes the sound of rivers, monsoon rains, thunder and wind blowing through grass. Animals, including elephants, insects and the calls of many birds also appear. There are also the sounds of people worshipping in temples, monasteries and shrines, using bells, gongs, cymbals, horns and drums. The scent is of sandalwood.

Length: about 8 minutes on a loop

Nature Spirits

Panel on the right:

Nature spirits

Covered in forests and rich agricultural lands, the many separate states and empires of ancient India were watered by immense rivers and monsoon rains. Most people lived in rural communities where nature spirits, including sacred snakes, were believed to inhabit the world around them.

From 200 BC onwards, colossal stone sculptures and thousands of smaller terracotta images were produced, showing the importance of these deities to the lives of ancient peoples. Such imagery influenced later religious art, and these spirits were believed to be so powerful that Jains, Buddhists and Hindus adopted them into their faiths.

Central showcase:

Snakes in human form

Whenever divine snakes adopt a human form, they keep some snake-related features. This limestone sculpture shows a nagini – a female sacred serpent. She has a woman's torso, but still has her snake tail and her canopy rising above her head. Such figures are erected at temples or by trees and bodies of water, where they are venerated for their life-giving powers.

Palnadu, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 500–600

Victoria and Albert Museum IM.309-1913

Purchased in 1913 from Robert Sewell (1845–1925), a civil servant and archaeologist working in Madras (now Chennai), India.

Cobra king

This limestone panel is carved with an image of a nagaraja or snake king. Divine snakes are usually represented as many-headed cobras and snake kings tend to have five or seven hoods. Images of sacred snakes are often placed at entrances to sacred buildings – whether Hindu, Jain or Buddhist – to protect them. This panel once adorned a Buddhist stupa (relic mound) at Amaravati in south-east India.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 700–900 British Museum 1880,0709.61

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887), the panel was taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Return to the section entrance, panel on the left:

Yakshas – male nature spirits

Yakshas are male nature spirits associated with trees, mountains, bodies of water and wealth. Devotees placated such deities – some with frightening expressions – with offerings, hoping to receive blessings and good fortune in return. They used massive stone figures for collective worship and smaller terracotta ones for personal devotion. Widespread across India, yakshas were gradually adopted by Jains, Buddhists and Hindus, who used their imagery and attributes when they began to depict their gods and enlightened teachers in human form.

Showcase on the left:

Image caption:

Map showing the places where many of the devotional images in this part of the exhibition are from with modern-day country and regional names for context.

The king of yakshas

Carrying a cup filled with alcohol and a bag of money, this sandstone figure (1) is of Kubera, the king of yakshas. He is also the god of wealth, a fact emphasised by his potbelly and plentiful jewellery. Still part of Hindu rituals today, Kubera is sometimes prayed to alongside Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth. Their images appear together on coins used in rituals, such as these two gold ones (2) and those attached to this lamp (3).

1

Possibly Kaman, Rajasthan, India, AD 400–600

Victoria and Albert Museum IM. 322-1921

Donated by Major E.A. Weinholt.

2, 3

India, 2024

British Museum 2025,4001.2-3 and 2025,4001.1

Donated in 2024 by Sushma Jansari, Curator of South Asia Collections at the British Museum.

Large image on wall:

Colossal stone figure of a male nature spirit from about 100 BC, perhaps representing Kubera, the king of yakshas, Vidisha Museum, India.

Photo: © American Institute of Indian Studies

Grimacing yakshas

Yakshas can be unpredictable. While some grant prosperity, others can make life difficult if they are not properly appeased. This quality is captured by the fierce expressions and teeth-baring grins on these yakshas. Leaves sprout above the ears of the large sandstone head (4), possibly connecting him with trees. The smaller terracotta figures (5–6) hold animals, likely goats, perhaps representing the sacrificial offerings made to them.

4

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 100–300

The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford EA1994.95

Purchased in 1994.

5

North West Frontier Province, Punjab, Pakistan, 300–100 BC

British Museum 1945,0417.24

Collected before 1945 by Eustace Chisholm, who worked for the Punjab Police.

Donated by his son A.D. Chisholm.

6

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, 300–100 BC

British Museum 1967,0221.20.19

Purchased in 1967 from Colonel D.R. Martin.

Funded by the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund, which was set up by P.T. Brooke Sewell (1878–1958), a merchant banker, who created two funds for the British Museum to purchase artworks from Asia.

Friendly yakshas

Thousands of small terracotta yakshas (7–11) have been found throughout northern India. Shaped by hand or in moulds from about 200 BC onwards, their exact purpose is unclear. They were perhaps venerated as deities in household shrines or left as offerings at religious sanctuaries. The small opening between their clasped hands possibly held a blossom, a leaf or even incense. The face of the rare bronze yaksha (12) has been worn smooth by devotees repeatedly touching it.

7

Chandraketugarh, West Bengal, India, 100 BC – AD 100

Victoria and Albert Museum IS.133-1999

Purchased by the V&A from Danny Biancardi.

Purchased with the assistance of Anna-Maria and Fabio Rossi.

8

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 1–300

British Museum 1967,0221.20.23

Purchased in 1967 from Colonel D.R. Martin.

Funded by the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund.

9

North India, 200–1 BC

British Museum 1904,0516.2

Donated in 1904 by Dr John Brighouse.

10

Kausambi, Uttar Pradesh, India, 100 BC – AD 100

British Museum 1942,0214.18

Purchased in 1942 from Sotheby's auction house.

11

Kausambi, Uttar Pradesh, India, 200 BC – AD 100

British Museum 1942,0214.20

Purchased in 1942 from Sotheby's auction house.

12

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 1–300

British Museum 2003,1003.3

Purchased by Dr Achinto Sen-Gupta (1932–2013) during a visit to Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Donated in 2003 by Dr Achinto Sen-Gupta.

Panel on the left:

Yakshis – female nature spirits

Yakshis are powerful female nature spirits able to bestow abundance and fertility, as well as death and disease. Depicted as full-figured bejewelled women standing by fruit or blossom-laden trees, these deities sometimes have weapons in their hair or hold a child. As with male nature spirits, their importance to the lives of ancient Indians is reflected by the high number of images found across the subcontinent. Originally independent goddesses, many yakshis were given male consorts when adopted into Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism.

Showcase on the left:

Powerful yakshis

The female nature spirits on these moulded terracotta plaques are represented by imagery linked to fertility and plenty. Here, yakshis are depicted touching the head of a boy (1), holding a pair of fish (2) and carrying some flower blossoms (3). Although the names of these deities are mostly unknown today, the sheer number of plaques discovered shows that worship of yakshis was central to the daily lives of people in India.

1

Possibly Mathura or Kausambi, Uttar Pradesh, India, 200–1 BC

Victoria and Albert Museum IS.118-1999

Bequeathed by Alexander Biancardi.

2

West Bengal, India, 100 BC – AD 100

Victoria and Albert Museum IS.119-1999

Bequeathed by Alexander Biancardi.

3

North-east India, 200–1 BC

Musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris MA3324

Purchased in 1971.

Predator to protector

Like Hariti depicted in this sandstone panel (back), some yakshis became prominent, popular goddesses. According to Buddhist tradition, Hariti was associated with smallpox, and the stealing and killing of children to feed her large family. To show Hariti how much these parents were suffering, the Buddha briefly hid one of Hariti's children beneath his rice bowl. She was so distraught that from that moment on she vowed to protect all children and women in childbirth.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 100–200

The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford EA1971.36

Purchased with the assistance of the Friends of the Ashmolean Museum.

Enduring goddesses

Child-devouring and protective yakshis are still venerated today. Isakki and Pecci are worshipped in Tamil Nadu, India's southernmost state, and among Tamil communities living elsewhere. In this bronze figure from the 1600s (4), Isakki holds a child. Devotees believe that such goddesses were women who perhaps died during pregnancy or childbirth and were later deified.

4

Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu, India, 1600–1700

British Museum 1998,0616.24

Collected by lawyer and film producer Joseph H. Hazen (1898–1994).

Donated in 1998 by his artist daughter Cynthia Hazen Polsky (1939–2024).

Image caption:

The goddess Pecci is venerated as Periyacci Amman in Sri Veeramakaliamman Temple, Singapore.

Photo © Sureshkumar Muthukumaran

Weapon-wielding goddesses

Yakshi images were mould-made in their hundreds. The moulds, like this terracotta example (5), rarely survive. Yakshis are always depicted as full-figured, extravagantly bejewelled women standing and looking directly at the viewer, as seen on this terracotta plaque (6). Sometimes the hair of yakshis from eastern India is decorated with sprays of weapons, such as elephant prods, spears, axes and tridents, suggesting a powerful warrior-like personality.

5

Chandraketugarh, West Bengal, India, 100 BC – AD 100

The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford EA1993.35

Presented by the Friends of the Ashmolean Museum.

6

Tamluk, West Bengal, India, 100–1 BC

The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford EAX.201

Transferred in the early 1960s from the Oxford Indian Institute.

Image caption:

Yakshi from eastern India

hair decorated with 5 different weapons

scattered flowers

raising girdle around her hips

squatting yakshas

Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Flowers not weapons

This limestone yakshi was carved hundreds of years after the terracotta figures with weapons in their hair, but she also has weapons in her hair. The lotus flowers she holds link her to fertility. While the religious context is different, the imagery remains similar, showing the continued importance and relevance of such symbols. She was probably placed at the entrance to a Buddhist shrine.

Possibly Goli, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 1–200

British Museum 1955,1017.1

Donated by P.T. Brooke Sewell Esq. in 1955.

Showcase on the left:

Goddess of good fortune

The goddess Lakshmi has yakshi origins and is one of the most popular deities in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. This basalt lintel (back) is from a Buddhist context. Here, she sits on a lotus blossom, while elephants pour water over her. Their dark bodies symbolise monsoon clouds filled with much-anticipated rain, ready to bring the earth to life. Gaja-Lakshmi – elephant Lakshmi in Sanskrit – so successfully conveys the message of abundance and fertility that representations have changed very little over thousands of years, as seen in this depiction painted about 1780.

Lintel, Pitalkhora Cave Four, Maharashtra, India, 200–100 BC

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai S.66.57

Gouache on paper, Bundi District, Rajasthan, India, about 1780

British Museum 1956,0714,0.32

Purchased in 1956 from Guy Caunce.

Image caption:

Lotus flowers.

Image © Dinodia Photos / Alamy Stock Photo (ID GP7NXJ)

Panel on the left:

Nagas and naginis – snake spirits

Nagas and naginis are male and female serpent spirits who control life-giving waters. These nature spirits grant wealth, fertility and protection, but they can also kill with a single bite. Among the most ancient deities to be venerated in India, they are usually depicted as many-headed cobras. Even when adopting human form some snake-like features remain, such as a cobra tail or hood, often described as a canopy. Such was their enduring power and popularity that they were incorporated into Jain, Buddhist and Hindu art.

Showcase on the left:

Snakes and farming

The link between nagas, naginis and farming is seen through the imagery of Balarama, originally a god of agriculture. In these sandstone sculptures, he is shown resting a plough on his shoulder. His rounded belly, the money bag or flask containing alcohol and the seven-headed snake canopy above his head reflect his yaksha origins. In later images, only his snake canopy remains. Today, he is known as the brother of the popular Hindu god Krishna.

left: Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 300–500

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin I 12

Purchased in 1907 from the estate of Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner (1840–1899), a linguist who founded the Oriental Institute in 1883 and the Shah Jahan Mosque in 1889, both in Woking, UK.

right: Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 100–300

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin I 5781

Purchased in 1976.

Mighty serpents subdued

The stories and imagery in these modern paintings and sculpture have ancient origins. They show Hindu gods taming the powerful and ancient snake kings Kaliya, Vasuki and Ananta Sesha. In the top painting (1) Krishna is seen stamping on the many heads of Kaliya before granting him mercy. In the painting below (2) a subdued Vasuki is shown being used as a churning rope by gods and malevolent beings. In the cast copper alloy sculpture (3) the Hindu god Vishnu reclines on Ananta Sesha's coils while being sheltered by his five snake hoods.

1

Rajasthan, India, 1790–1810

British Museum 1880,0.2253

Acquired before 1980.

2

Rajasthan, India, about 1800

British Museum 1940,0713,0.26

Collected by Major Edward Moor (1771–1848), probably while serving in the East India Company army.

Donated in 1940 by Mrs A.G. Moor.

3

Srirangam, Tamil Nadu, India, 1700–80

British Museum 1805,0703.476

Collected in India during the 1780s by military officer and surgeon David Simpson, then bought in 1792 by antiquarian Charles Townley (1737–1805) from Christie's auction house. It was then purchased by the British Museum from Townley's estate in 1805.

Image caption:

Ancient snake kings are subdued

Shiva with Vasuki wrapped around his neck

Vasuki, the many-headed snake, is wrapped around Mount Mandara and used as churning rope

Mount Mandara rests on the back of Kurma, a tortoise and one of the god Vishnu's bodily forms on earth

small gold vessel containing the elixir of immortality

Lakshmi seated on a lotus flower

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Protective snake kings

Jain and Buddhist stories feature serpent kings sheltering meditating enlightened teachers from storms. These bronze sculptures show the Jain teacher Parshvanatha (4) with a snake rising up his back and the Buddha (5) sitting on top of snake coils. Each figure has a serpent's hood raised protectively over their head. Parshvanatha's snake – Dharanendra – became his divine attendant.

4

Deccan, India, 1300–1500

British Museum 1914,0218.4

Donated in 1914 by Henry Oppenheimer (1859–1932) through the Art Fund (as NACF).

5

Sri Lanka, about 1800–80

British Museum 1898,0702.24

Collected by Hugh Nevill (1847–1897), a civil administrator of the British colonial government in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and purchased in 1898 from his brother Ralph Nevill.

Showcase on the left:

Snakes and natural features

The veneration of divine snakes by followers of different religions is still popular across India today. It centres on natural features, such as abandoned termite mounds, as well as on the placement of devotional images in temples or by sacred trees. Sculptures of rearing snakes, like this stone plaque, have been placed by tree shrines for over a thousand years. Dating them can be difficult, as it relies on being able to date the archaeological context within which they were discovered, or by stylistic comparison with dated objects.

Deccan, India, 1600–1700

British Museum 1900,1011.1

Donated in 1900 by W. Frazer Briscoe.

Image caption:

Snake sculptures sprinkled with coloured powder near a shrine dedicated to the snake goddess Manasa.

Photo © Claudine Klodien / Alamy Stock Photo (ID GNYA96)

Protecting the dead

Devotees of different religious traditions believe divine snakes have protective powers, which is why they are often found carved into panels that decorate sacred shrines, or sometimes in ancient Indian burials. This stone sculpture of a rearing three-headed snake was found in a brick burial shaft with a group of terracotta vessels. The lack of an inscription makes it impossible to determine whose ashes were once buried in this grave.

Mansar near Ramtek, Maharashtra, India, AD 400–500

British Museum 1930,1007.1; 1930,1007.23; 1930,1007.18 and 1930,1007.5

Found in 1928 in a mine in Mansar, Central India, managed by Thomas Arthur Wellsted. The ashes were not given to the British Museum.

Donated in 1930 by Thomas Arthur Wellsted.

Showcase on the left:

Opposing forces

Manasa is a snake goddess venerated by Buddhists and Hindus alike for her ability to provide prosperity, children and protection from snakes. She can also cause harm with a deadly snakebite. Depicted as a beautiful woman surrounded by snakes, she usually holds a serpent or, as in this cast copper alloy sculpture, a child. Her story is still shared with the public today by travelling storytellers who use scroll paintings like this paper one (left) as visual props.

Sculpture, Eastern India, about AD 750

British Museum 1969,0115.1

Purchased in 1969 from dealers Spink & Son Ltd.

Funded by the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund.

Scroll painting, Gurupada Chitrakar (1965–2021), Kolkata, West Bengal, India, 2000–6

British Museum 2006,0209,0.1

Purchased in 2006 from the artist.

Panel on the left:

Animal-headed nature spirits

Some nature spirits are depicted with the bodies of humans and the heads of animals, such as lions and elephants. Stylistically, they both share many yaksha features, such as their squat bodies and rounded bellies, which are associated with good fortune. The veneration of elephant-headed Ganesha, in particular, crosses religious and social boundaries.

The lion-faced god

These sandstone sculptures depict lion-faced deities. The larger one (1) has the squat figure and rounded belly of a yaksha plus the fierce face of a lion. He can also be seen in the upper left corner of the Buddha image (2) holding a club and raising his index finger menacingly. In this sculpture, the god is part of an army trying to stop the Buddha's enlightenment. It is led by Mara, the personification of death and worldly temptation.

1

Madhya Pradesh, India, AD 400–500

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai L.82.2/68

2

Possibly Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 600–700

British Museum 1880.11

Transferred to the British Museum in 1880 following the closure of the India Museum, London.

The elephant-headed god

Ganesha's yaksha origins are demonstrated by his elephant head and potbelly. Originally a deity of crossroads and thresholds, he now holds an exalted place as the first deity invoked in Hindu ritual. This fragment of a terracotta plaque shows a scene of elephant-masked musicians and dancers performing before a shrine, suggesting the importance of elephants to ancient ritual activity. Ganesha is one of the most well-known and beloved gods for Hindus, as well as for some Jains and Buddhists.

Chandraketugarh, West Bengal, India, 100–1 BC

The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford EA1997.16

Purchase funded by an anonymous donor.

Identifying Ganesha

Early images of Ganesha, like this sandstone figure, show him holding a bowl of sweets, linking him to ideas of plenty. In later depictions (back right) he has gained additional features, such as a snake cord around his torso and four arms holding an axe, prayer beads, his own broken tusk and sweets. Many Hindu gods are further linked to nature by their animal vehicles. Ganesha's is a rat or mouse. This is fitting in a rural setting, as they both cause problems for farmers, and because he is the god of placing and removing obstacles.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 350–400

Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich (MFK), Mu.197

Purchased in 1911 from Lucian Scherman (1864–1946).

back right: Odisha, India, 1100–1200

British Museum 1872,0701.62

Collected between 1777 and 1828 by Major General Charles Stuart (about 1758–1828), while serving in the East India Company army. On his death, it was sold at auction to John Bridge (1755–1834), a partner in a goldsmithing firm.

Donated in 1872 by Mrs John Bridge, Miss Fanny Bridge and Mrs Edgar Baker.

Jain art

Panel on the left:

Jain art

Emerging more than 2500 years ago at the same time as Buddhism, Jainism is still practised in India and across the globe. Jains follow the teachings of twenty-four tirthankaras – enlightened beings – who are human rather than divine, and are attended by male and female nature spirits. They also worship some gods. Jains follow the Three Jewels – right faith, right knowledge, right conduct – to enable their immortal souls to live in a state of bliss. Ahimsa (non-violence) is central to their faith, as is the belief that humans, animals and plants have living souls.

Jain art focuses on representations of tirthankaras. The earliest certain sculptures of these enlightened teachers were made about 2000 years ago in the ancient city of Mathura in northern India. Carved in human form, they were a major innovation in the religious art of India, partly inspired by earlier sculptures of nature spirits.

Central plinth:

Parshvanatha reaches enlightenment

Parshvanatha, the 23rd tirthankara, is portrayed on this sandstone sculpture. A malevolent spirit sent a rainstorm – symbolised by the storm clouds – to disturb his meditation, prompting his divine attendant Dharanendra to spread his snake hoods and provide cover. Protected from the weather, the enlightened teacher was able to continue meditating, eventually achieving enlightenment.

Gyraspur, Madhya Pradesh, India, AD 600–700

Victoria and Albert Museum IS.18-1956

Possibly donated in 1830 to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society by Lieutenant Jefferson, a Royal Navy officer, and later transferred to the Yorkshire Museum, UK. Purchased in 1956 by the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Image caption:

Parshvanatha reaches enlightenment

hands and drums representing heavenly music

heavenly garland bearers

Dharanendra uses his snake canopy to shelter Parshvanatha

Padmavati, the snake queen, also protects Parshvanatha with a parasol held above the snake canopy

attendant with a fly-whisk

lion

yaksha

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Wall on the left:

The Jain universe

The Jain universe is divided into three worlds – the hells, the middle world and the heavens. As beings advance spiritually, their souls are eventually liberated from the cycle of rebirth and reach the heavens. At the centre of this painted cotton map are the two and a half continents of the middle world, where humans reside. The mountains, rivers and forests of the continents are surrounded by a salty ocean inhabited by fish, crocodiles and turtles, and with lotus flowers floating on its surface.

Gujarat or Rajasthan, India, 1700–1900

British Museum 2002,1019,0.1

Purchased in 2002 from Joss Graham Oriental Textiles with contributions from the Luigi and Laura Dallapiccola Foundation (by courtesy of Professor Anna Dallapiccola) and from the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund.

Image caption:

The Jain middle world

mountains running east to west

the island at the centre where Mount Meru is and humans live

salty ocean with fish, crocodiles, turtles and lotus flowers

golden vases representing the 4 compass points

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Showcase on the right:

Life of an enlightened teacher

This Jain manuscript illustrates key moments in the life of Parshvanatha, the 23rd tirthankara. Like all enlightened teachers he was born into the human middle world (1). Having given away his possessions (2), Parshvanatha became a wandering ascetic. He gained enlightenment through meditation (3) and when he died his soul reached the heavens (4). He is usually depicted with a many-headed serpent above his head, imagery that links him to nature spirits. Here, he is seen rescuing a family of snakes from a sacred fire (5).

Western India, 1512

Wellcome Collection Gamma 453 Folio 74, 75, 76, 77 and 79

Possibly purchased in 1919 on behalf of the Wellcome Collection by Dr Paira Mall (1874–1957). He collected manuscripts and objects from India and parts of East Asia between 1911 and 1921.

Image caption:

Parshvanatha sits on a throne meditating at the top of the universe with Dharanendra's snake hoods spread above him.

Image © Wellcome Collection, London

Materials matter

Vibrant colours derived from natural, non-animal sources were used in ancient and contemporary Jain art, including these sacred manuscript paintings. All of the paint used in this exhibition is vegan, including the golden colour of this section.

'The principle of non-violence in Jainism means holding all life-forms sacred – therefore NOT using animal-derived paint and materials throughout this exhibition has been an important consideration'.

Arshna Sanghrajka

Community Advisory Panel member

Showcase on the right:

Excavating ancient Jain shrines

Mathura was one of the most important cities in ancient northern India – a centre of trade and religious activity with many Jain shrines, as well as Hindu and Buddhist temples. Little is known about these sacred Jain buildings. This is partly because valuable archaeological information was lost as local people dug them up to reuse the building materials. It is also because colonial officials carried out poorly planned and recorded excavations, making it impossible to date the sculptures that adorned the shrines or to identify where they were from. The Jain part of ancient Mathura is now called Kankali Tila.

Image captions:

Local people working on the site in 1889 during Dr Alois A. Führer's mismanaged excavations.

Image © From the British Library Collection: 1710.b.1.16 plate 11a

What Kankali Tila, the Jain part of Mathura, looks like today.

Photo © Sureshkumar Muthukumaran

Missing evidence

The inscription on this dated sandstone panel describes a new temple or shrine dedicated to one of Mathura's goddesses. Goddesses are worshipped by Jains, Buddhists and Hindus, so without accurate archaeological records it is impossible to establish the religion of the donor or the shrine, or even the original location of the shrine.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 137

British Museum 1887,0717.53

Donated in 1887 by Major General Sir Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893), a British Army engineer and scholar, who founded the Archaeological Survey of India in 1861.

Showcase on the right:

Sacred donations

Religious institutions relied on donations to flourish. This sandstone carving from a temple or shrine doorway depicts male and female devotees, possibly donors to the sacred monument itself. Poor archaeological record keeping by colonial archaeologists means that its date is approximate and its religious affiliation unclear.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 100–300

British Museum 1953,0423.1

Purchased in 1953 from dealers Luzac & Co.

Showcase on the right:

Shared sacred imagery

These sandstone railings once surrounded a Jain or Buddhist stupa – a dome-shaped memorial shrine built over sacred relics. The devotional art of both religions was produced at the same workshops in Mathura, sharing artistic motifs and divinities, such as this yakshi (left). The stitched tunic of the pipe player (right) indicates there were links to Iran and Central Asia, suggesting Mathura's ethnic and cultural diversity. Musicians and dancers are portrayed on many of this site's sculptures, showing how integral such activities were to Jain, Buddhist and Hindu worship.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 100–200

British Museum 1975,1027.1 and 1965,0226.1

Purchased with the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund in 1975 and 1965 from dealers Spink & Son Ltd.

Panel on the plinth opposite, extreme right:

Developing Jain art

Over the course of many centuries, important innovations in sacred art were made in Mathura, a major ancient centre of production for Jain, Buddhist and Hindu devotional sculpture in northern India. The earliest known and definite images of Jain tirthankaras (enlightened teachers) depicted in human form are from here, perhaps dating to about 100 BC. A uniquely Jain innovation are ayagapatas. These are square or rectangular tablets of homage depicting tirthankaras, shrines and deities. All of these sculptures are carved from the mottled pink sandstone for which Mathura is well-known.

Image caption:

Map showing the places where many of the devotional images in this part of the exhibition are from with modern-day country and regional names for context.

Remembered in miniature

None of the stupas – dome-shaped memorial shrines built over relics – from the Jain complex in Mathura survive today. There are, however, some artistic representations of them, such as on this decorative sandstone piece (back right) originally placed above a doorway. It shows devotees approaching the shrine with clasped hands and a tray of offerings held aloft. There are three tablets of homage next to the stupa, placed on pedestals.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 1–100

Courtesy: on loan from the National Museum, New Delhi (India) J.555

Evolving style

Ayagapatas are stone slabs carved with images of Jain enlightened teachers, deities and sacred symbols. Originally, they might have been stone platforms placed under trees on which devotees placed offerings to nature spirits. Jain ayagapatas often have inscriptions from donors, many of whom were women, who gained spiritual merit through their donations. The inscription on this slab (back left) suggests that it may have been donated by a musician.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, about 20 BC

Courtesy: on loan from the National Museum, New Delhi (India) J.249

Recycling ancient sculpture

This fragment of a sandstone tablet of homage has two sides, which were carved at different times. Here, the original and earliest side is decorated with carvings, possibly representing the Jain cosmos, and a celestial garland bearer approaching a tirthankara, seated in meditation. The slab was reused to retain the spiritual merit of the original donation.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 1–100

British Museum 1901,1224.10

Excavated at the ancient site of Kankali Tila, Mathura, then placed in the Lucknow State Museum, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Donated in 1901 by Lord George Francis Hamilton (1845–1927), the Secretary of State for India, on behalf of the British Government of India.

Image caption:

The back of this ayagapata was carved between AD 200 and 400. It depicts a Jain enlightened teacher, but only his lower half survives.

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Recognising an enlightened teacher

Jain enlightened teachers are always shown in one of two meditation poses – seated or standing. The way the arms are positioned on this serene looking sandstone figure (back right) suggests he was seated. The sacred symbol of an endless knot on the chest confirms that he is a tirthankara, while the lotus-petal halo around his head highlights his spiritual nature.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 200–300

British Museum 1901,1224.5

Excavated at the ancient site of Kankali Tila, Mathura, then placed in the Lucknow State Museum, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Donated in 1901 by Lord George Francis Hamilton (1845–1927), the Secretary of State for India, on behalf of the British Government of India.

Identifying through symbols

All 24 Jain enlightened teachers have identical bodies because they are depicted as they are about to enter the heavens – the realm of liberated souls at the top of the universe. So that devotees can tell them apart, symbols from stories connected with their lives are used. This stone sculpture (back left) depicts two tirthankaras standing in meditation. On the left, Rishabhanatha – the first tirthankara – has long hair and a bull, seen here below his feet. On the right, Mahavira – the 24th tirthankara – has lions crouching beneath his feet.

Odisha, India, AD 1100–1200

British Museum 1872,0701.99

Collected between 1777 and 1828 by Major General Charles Stuart (about 1758–1828), while serving in the East India Company army. On his death, it was sold at auction to John Bridge (1755–1834), a partner in a goldsmithing firm.

Donated in 1872 by Mrs John Bridge, Miss Fanny Bridge and Mrs Edgar Baker.

Queen of snakes

Some divine attendants are also popular figures of worship because of their individual qualities. The nature spirit and queen of snakes Padmavati can cure snakebites and grant wealth. She is the female attendant of Parshvanatha, the 23rd tirthankara, who can be seen sitting above her snake canopy in this stone sculpture. A protective deity, Padmavati carries a shield and sword, now broken, in her hands.

Deccan, India, AD 1000–1200

British Museum 1957,1221.1

Formerly in the collection of Sir William Rothenstein (1872–1945), an artist who was inspired by Indian paintings and sculpture, travelling there in 1910.

Donated by P.T. Brooke Sewell Esq. in 1957.

Divine attendants

Nature spirits have long been venerated at Jain shrines. Over time, and as depicted in this bronze sculpture, some became associated with specific enlightened teachers, as their divine male and female attendants and protectors. Tirthankaras cannot intervene in human affairs because they have attained enlightenment, however their attendants can answer people's prayers, so are also venerated by Jain devotees.

Deccan, India, AD 800–1000

British Museum 1914,0218.13

Donated in 1914 by Henry Oppenheimer (1859–1932) through the Art Fund (as NACF).

Ancient goddess of knowledge

Jains venerate the goddess Sarasvati as both the personification and guardian of all knowledge. This marble statue shows her carrying a manuscript and prayer beads in her lower and upper right hands, and probably a musical instrument and lotus flower in her now-broken left hands. One of the Jains' most ancient goddesses, Sarasvati is also connected with the arts and music, and is one of Hinduism's principal goddesses.

Western India, 1050–1100

British Museum 1880.349

Acquired before 1980.

Knowledge leads to enlightenment

These sculptures are Jain goddesses of knowledge. Like this limestone figure (back) they are usually shown carrying sacred palm-leaf manuscripts and often a pen. The attendant to the right of the goddess holds up an inkpot for her to dip her pen into. The bronze Vidyadevi holds a manuscript and lotus flower.

Limestone sculpture, Rajasthan, India, about AD 1000

British Museum 1967,0714.1

Purchased in 1967 from S.Y. Sardesai.

Funded by the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund.

Bronze sculpture, Deccan, India, AD 900–1000

British Museum 1957,1021.1

Formerly in the collection of Captain Raymond Johnes, who was in active service 1927 to 1970.

Donated by P.T. Brooke Sewell Esq. in 1957.

Image caption:

Four small bronze devotional sculptures have been placed either side of the larger marble one of a tirthankara at the Jain Centre in Leicester, UK.

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Panel on the left:

Goddesses of knowledge – the Vidyadevis

There are many deities in Jainism aside from the male and female attendants of tirthankaras. Most are female and some are shared with Buddhism and Hinduism. The ultimate goal for Jain devotees is to attain enlightenment by following the Three Jewels – right faith, right knowledge and right conduct. To help them, they have sixteen goddesses of knowledge called Vidyadevis – vidya means knowledge in Sanskrit and devi means goddess. Usually depicted holding a manuscript and sometimes a pen, they are easy to identify.

Film on the left:

Daily devotion, 2025

Every day, Manjula Shah volunteers at the Jain temple at the Oshwal Centre in Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, UK. She assists the priest in caring for and making offerings to the sacred images of the tirthankaras. Here, she explains how performing these rituals on behalf of the community also enrich her own life.

The film is narrated by Manjula Shah. There are sounds of birds chirping, traffic, sandalwood being ground, people praying, metal jewellery being placed on a marble statue and a floor being swept.

Length: about 90 seconds

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Buddhist art

Panel on the right:

Buddhist art

Buddhism originated in northern India alongside Jainism more than 2500 years ago. It is based on the teachings and philosophy of Siddhartha Gautama, a prince who became known as the Buddha after gaining enlightenment. He taught the Four Noble Truths, helping others to also achieve enlightenment. The Buddha's followers spread his message across India to Sri Lanka and beyond. Today, different Buddhist traditions are practised across the world.

Buddhist art focuses on representations of the Buddha and his life. For reasons that are unclear, he was first depicted using symbols, such as footprints or a tree. During the first century AD, he began to be represented in human form, incorporating some nature spirit features. Figurative representations of the Buddha remain an integral part of contemporary Buddhist worship.

Central plinth:

Changing representations of the Buddha

This slab, now carved on both sides, is from a sacred shrine at Amaravati in south-east India. It was part of a decorative band of sculpture around the circular base of a Buddhist monument known as a stupa.

This side was carved in about AD 250, and depicts the Buddha in human form, a significant innovation in Buddhist art. Standing at the stupa entrance, his right hand is raised in a gesture to bestow protection and dispel fear. The other side was carved earlier in about 50–1 BC at a time when the Buddha was represented through symbols, not figuratively.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, about AD 250

British Museum 1880,0709.79

Excavated by Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1754–1821), donated to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Image caption:

The Buddha stands at a stupa entrance

dome

decorative ring around the stupa

lion on top of a pillar

coping stones

the Buddha as a man

railings decorated with lotus flowers surround the stupa

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Buddha represented symbolically

This is the original and earliest side of the slab, carved in about 50–1 BC. It shows devotees with their hands clasped in reverence beside symbols representing the Buddha – an empty throne, footprints, a tree and a sacred parasol.

In about AD 250 during a major renovation of the Amaravati sacred shrine, this slab was turned over and an image of the stupa carved onto the back (see the other side). This time, however, the Buddha was shown in human form.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, 50–1 BC

British Museum 1880,0709.79

Excavated by Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1754–1821), donated to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then transferred to the British Museum in 1880. Formed in 1600, the East India Company traded with – and then ruled – large parts of India. Company rule ended in 1858 with the British Crown assuming direct control until Indian Independence in 1947.

Image caption:

Symbols of the Buddha

Bodhi tree, under which the Buddha gained enlightenment

parasol

empty throne

footprints

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Plinth to the left, extreme right:

Image caption:

Map showing the places where many of the devotional images in this part of the exhibition are from with modern-day country and regional names for context.

The Buddha's early life

This limestone panel is carved with scenes from the Buddha's early life. Queen Maya (bottom right) gives birth to Prince Siddhartha Gautama – the future Buddha. She is depicted as a full-figured, bejewelled female nature spirit standing by a tree. The baby is then presented to the clan deity, a potbellied male nature spirit emerging from a tree (bottom left). In both scenes, Prince Siddhartha's presence is represented by tiny footprints on cloth.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 1–100

British Museum 1880,0709.44

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887), the panel was taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Image caption:

Birth of the Buddha

Queen Maya, the Buddha's mother, depicted as a yakshi next to a tree

tiny footprints representing the infant Prince Siddhartha Gautama, the future Buddha

yaksha emerging from a stone platform, part of a tree shrine

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Divine snakes resurface

The great stupa at Amaravati was the largest and most impressive of many Buddhist shrines in south-east India. It was highly decorated with ornate limestone carvings of scenes from the Buddha's life and sacred symbols, such as protective snakes. This drum slab from the decorative ring at the base of the stupa shows a five-headed snake rearing up and ready to strike, as it guards the sacred monument.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 50–100

British Museum 1880,0709.39

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Ancient centre of devotional art

The earliest dated figurative sculptures of the Buddha that survive today were produced in the ancient and sacred city of Mathura in northern India from AD 129 onwards. The sculptors of Mathura added a spiral curl of hair onto the Buddha's head and such images are called Kapardin Buddhas, after the Sanskrit for shell. The full figure and arm positions of this seated sandstone Buddha are similar to those of male nature spirits. The dot between the eyebrows is a symbol still linked with the Buddha, representing spiritual wisdom. These sculpture workshops also produced Jain devotional art.

Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, about AD 200

Courtesy: on loan from the National Museum, New Delhi (India) L.55.25

Oldest dateable image of the Buddha

This cylindrical gold reliquary (1), inset with garnets and turquoise, and the stone container (2) it was kept in were donated to Bimaran stupa by a man named Shivarakshita. The name means 'protected by Shiva', suggesting a family background involving the worship of the Hindu god Shiva. His gift also included beads and some coins from the reign of a governor named Mujatria (AD 75–100). The date of the coins means the image on the reliquary might be the oldest representation of the Buddha in human form that can be securely dated. According to the inscription, the reliquary once held some of the Buddha's relics.

1

'Bimaran Casket', British Museum 1900,0209.1

2

Steatite reliquary, British Museum 1880.27

Bimaran, Darunta, Afghanistan, about AD 100

Excavated in 1834 from Bimaran Stupa 2 by Charles Masson (1800–1853), an East India Company soldier and archaeologist, and then placed in the East India Company's India Museum, London. After it closed in 1880 the reliquary, beads and coins were transferred to the British Museum. The gold reliquary initially went to the India Office, and then to the British Museum in 1900.

Independent innovation

The earliest images of the Buddha in human form were created independently in Mathura (India), the Swat Valley (Pakistan) and Gandhara (Pakistan and Afghanistan). It is unclear why this change in representation happened, but during colonial rule in India European scholars proposed a theory. They believed that the sculptors of Gandhara made Greek- and Roman-style images of the Buddha for Greek patrons. This is no longer considered valid, as the evidence suggests this change had more local origins. This stone Buddha, for example, wears traditional Indian unstitched clothing.

Jamalgarhi, Gandhara, Pakistan, AD 200–300

British Museum 1895,1026.1

Donated in 1895 by collector Thomas Eustace Smith (1831–1903), owner of Smiths Dock Company, a shipbuilding business in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Panel:

Spiritual patronage

Amaravati stupa was the largest and most magnificent Buddhist shrine in south-east India. Building it was an enormous project. Its construction, embellishment and, over time, extension and refurbishment were funded by many generous donors, who were rewarded with spiritual merit for their patronage. Inscriptions on the shrine reveal that most of the donors were part of the wealthy urban elite, including monks, nuns and their disciples, royal officers, and artisans such as perfumers. Many donations were also made by family groups.

Opening up the archives

Ongoing research in museum archives all around the world is revealing the many different people, including South Asians and Europeans, who sold and donated objects to the British Museum. The exhibition labels provide information about how each devotional image on display came to be at the British Museum.

'These days, when I take students to a museum to study objects, someone will always ask me, "How did it get here?" It's not possible to teach art history anymore, without reflecting on the provenance of the objects we teach and research about.'

Sujatha Meegama

Community Advisory Panel member

Donations from a king

The inscription at the top of this limestone panel explains how Pussagutta, the 'overlord of Kalinga' set up three great shrines. It is carved with five scenes, each showing a royal figure – depicted as the second largest person to the Buddha – wearing an elaborate headdress and rich jewellery. In the central scene, the ruler raises his clasped hands in veneration of the Buddha, who stands on the stupa's right.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 50–100

British Museum 1880,0709.20

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887), the panel was taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London. Following its closure, the panel was transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Women donors

Women who were part of the urban elite and had independent means made important donations to Amaravati stupa in order to obtain spiritual merit. This limestone drum slab was donated by an unnamed woman, a pupil of a monk named Budharakhata. It was originally over 3m high and formed part of the decorative ring around the shrine's base. The scene shows a king and his attendants, while the throne and deer of the partial scene above suggest the missing fragment was of the Buddha's First Sermon.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 50–100

British Museum 1880,0709.49

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Three women, one donation

This limestone railing pillar was donated by three women. All that is known about them is that they were named Samgha, Samghadasi and Kumala and described themselves as 'the wives of Lonavalavaka, Samgharakhita and Mariti'. Enclosed by two large lotus flowers, this carving possibly depicts Prince Siddhartha Gautama's Great Departure. This is when the future Buddha left his royal home and family to seek enlightenment.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 100–200

British Museum 1880,0709.37

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Giving together

To collectively gain spiritual merit, some families donated sculptures to Amaravati stupa. The inscription on this one reveals that it was gifted by a man 'together with his daughters, his sons and grandsons'. Figures venerating an empty throne can be seen on the remnants of the slab. The spoked wheel above the throne represents the Buddha's First Sermon.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 50–100

British Museum 1880,0709.50

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Protecting the Buddha's relics

Originally holding a seated lion sculpture, this block was donated to Amaravati stupa by Budhi and his sister Budha. One side is carved with an image of a male nature spirit holding up a lintel. The other shows elephants venerating Ramagrama stupa, which is encircled by rearing serpents. According to a Buddhist story, this stupa contained the Buddha's relics and the protective serpents stopped anyone from removing them.

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 50–100

British Museum 1880,0709.108

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Showcase on the opposite side, extreme left:

Discovery, destruction and dispersal

Having fallen out of use, the ancient stupa at Amaravati was rediscovered in the 1790s by men working for landowner Raja Vesireddy Venkatadri Nayudu (1761–1816). They reused the monument's bricks and limestone in various building projects, destroying its dome. In 1816, British officers began to document and excavate the remains. After Indian Independence in 1947, the work was taken on by professional Indian archaeologists. Some of the Amaravati sculptures are at the British Museum, but most are in the Government Museum in Chennai (formerly Madras) in south-east India.

Image captions:

Sketch by East India Company surveyor Colonel Mackenzie showing the base of Amaravati stupa after Nayudu's workforce had removed the dome, 1816

Image © From the British Library Collection: WD806

Amaravati stupa today with sculptures displayed around the modern brick structure.

Image © ephotocorp / Alamy Stock Photo (ID 2R5YXAG)

Panorama of colonial excavations

Section by section, Sergeant Coney took these photographs (1) from what had been the centre of Amaravati stupa. They show the sculptures around the circular edge of the site shortly after another destructive excavation there by colonial official J.G. Horsfall in 1880. It was carried out by order of the Duke of Buckingham, then Governor of the Madras (now Chennai) Presidency in India.

1

Andhra Pradesh, India, about 1876

British Museum Sewell, A1.1

Donated in 1926 through the Christy Collection by Mrs R. Sewell, widow of Robert Sewell (1845–1925), a civil servant working in Madras (now Chennai), India and one of the archaeologists who excavated Amaravati stupa in 1877.

Reusing materials from a sacred shrine

This sketch (2) shows the scale of the damage done to the stupa by men working for the local landowner in the 1790s – the stupa's dome has been completely removed. Its bricks were used for construction and the limestone burnt to make lime mortar or repurposed. The blue patch on the drawing represents the reservoir the Raja planned to build in its place.

2

Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, India, 1816

British Library Collection WD806

Purchased by the East India Company in 1823 from Petronella Jacomina Bartels (active 1821–3), widow of archaeologist Colonel Colin Mackenzie. After the East India Company closed in 1857, this drawing became part of the India Office Library and then, in 1982, part of the British Library.

Imagining a sacred shrine

This rare surviving ink drawing (3) by Sir Walter Elliot shows what he thought Amaravati stupa originally looked like. It is based on his knowledge and experience of the site and the sculptures that he excavated there in the 1840s. Although inaccurate, it does help scholars today understand how people in the past thought the different stupa components might originally have fitted together.

3

1845

British Museum 1996,1007,0.3

Acquired before 1996.

Drawings as records

Murugesan Mudaliar, a Tamil draughtsperson from southern India drew some of the Amaravati sculptures in 1854, almost 10 years after they had been dug up. Sir Walter Elliot, an East India Company administrator who excavated part of the stupa, sent more than 100 of the sculptures to the Company's India Museum in London. When this museum closed in 1879, the Amaravati sculptures were transferred to the British Museum, including those shown in Mudaliar's watercolour illustrations (4 and 5).

4, 5

Chennai, India, 1854

British Library Collection WD2261 and WD2256

Placed in the East India Company library in about 1854, the drawings became part of the India Office Library after the dissolution of the East India Company in 1857, and then part of the British Library in 1982.

Drawing details

Also made by Tamil artist Murugesan Mudaliar in 1854, these watercolours (6 and 7) show the fine detail of the sculptures of the great bodhisattvas Manjushri (9) and Vajrapani (10) when they were first excavated. They are now in relatively poor condition, as the delicate limestone deteriorated during the years they were stored outside before being moved to museums in India and the UK. The Amaravati sculptures at the British Museum are now stable and kept in a specially conditioned environment.

6, 7

Chennai, India, 1854

British Library Collection WD2242 and WD2269

Placed in the East India Company library in about 1854, the drawings became part of the India Office Library after the dissolution of the East India Company in 1857, and then part of the British Library in 1982

Experimental photography

Linnaeus Tripe, an officer in the East India Company army, photographed some of the Amaravati sculptures after they had been removed to Madras (now Chennai) in 1858. He tried a new type of photography, which unfortunately resulted in many poor quality images. This photograph (8) of the Buddhist goddess Cunda (11), however, shows how fine the carving was when she was first uncovered.

8

Andhra Pradesh, India, 1858

British Museum Tripe.A1.1

Helping others to enlightenment

This limestone sculpture (9) shows the great bodhisattva, Manjushri, as depicted in the drawing on the left (6). Bodhisattvas are beings who seek enlightenment, whereas great bodhisattvas have gained additional powers over many lifetimes, enabling them to perform miracles and help others on the path to enlightenment. Here, Manjushri – meaning 'gentle glory' in Sanskrit – holds a lotus flower, but is often shown wielding a sword symbolising the cutting through of ignorance to arrive at wisdom.

9

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 800–1000

British Museum 1880,0709.125

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Embodying the Buddha's power

The great bodhisattva Vajrapani – 'holder of the thunderbolt' in Sanskrit – is shown here (10) with his symbol by his halo. He embodies the Buddha's power and can be see in the sketch to the left (7). He is usually shown as an attendant standing next to the Buddha, so this sculpture might once have flanked a larger Buddha image.

10

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 800–1000

British Museum 1880,0709.126

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Buddhist goddess

A representation of the goddess Cunda was carved into this limestone panel (11) from Amaravati. Inspiring devotees in their spiritual practice, she bestows good health and fortune and provides protection against misfortune. Here, she sits below a parasol flanked by two seated Buddha images. Their hands are in the gesture of meditation.

11

Amaravati stupa, Andhra Pradesh, India, AD 800–1000

British Museum 1880,0709.127

Excavated in 1845 by Sir Walter Elliot (1803–1887) and taken to Madras (now Chennai), where it was placed in Old College at Fort St George and then in the Government Museum. In 1859 it was sent to the East India Company's India Museum, London and then, following its closure, transferred to the British Museum in 1880.

Compassion and protection

In different Buddhist traditions, Tara is venerated as a bodhisattva or goddess of compassion, protecting both travellers and navigators. This exceptional sculpture was cast in solid bronze and then gilded. Her right hand is extended in the mudra – Sanskrit for gesture – of giving. The medallion that ornaments Tara's elaborate hairstyle might once have contained a seated image of Amitabha – the Buddha of Infinite Light.

Sri Lanka, AD 700–800

British Museum 1830,0612.4

From 1813 until 1819, Sir Robert Brownrigg was the Governor of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In letters to the Museum he suggests that this image of Tara was found between Trincomalee and Batticaloa, both towns on the island's east coast.

Donated in 1830 by Sir Robert Brownrigg.

Colonial papers

This copy of a letter was written by Sophia Brownrigg on behalf of her husband, General Sir Robert Brownrigg, the former Governor of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). It is addressed to Mr Ellis, Principal Librarian of the British Museum and Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries. Brownrigg is offering the Society of Antiquaries a bronze sculpture that he 'found in the North East part of Ceylon, between Trincomalee and Baticaloa'. He thought it was the Hindu goddess Pattini, but it is actually Tara. Brownrigg eventually donated the sculpture to the British Museum.

London, 1830

Original Papers Volume VIII, British Museum

The Original Papers record series contains letters, reports and other written communication to the British Museum's Trustees and to the Principal Librarian Sir Henry Ellis (1777–1869), who was responsible for the Museum's library and collections.

Great bodhisattvas and deities

Mahayana Buddhism, which once flourished in Sri Lanka, involves the veneration of great bodhisattvas such as Tara (1) and Avalokiteshvara (2). They are compassionate beings with miraculous powers who delay reaching enlightenment themselves to help others on the path to enlightenment. Deities like Prajnaparamita (3), who personifies the wisdom that leads to becoming a Buddha, are also worshipped. Today, Sri Lankan Buddhists follow the Theravada school of Buddhism, meaning 'teaching of the elders'.

1, 2, 3

Sri Lanka, AD 600–800; AD 800–900 and AD 700–800

British Museum 1898,0702.142; 1898,0702.133 and 1898,0702.130

Collected by Hugh Nevill (1847–1897), a civil administrator of the British colonial government in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and purchased in 1898 from his brother Ralph Nevill.

The sacred in miniature

Many small, lathe-turned rock crystal reliquaries for holding sacred relics have been found at sites in Sri Lanka. Their shape mirrors that of Sri Lankan stupas, such as Thuparamaya stupa in Anuradhapura, believed to contain one of the Buddha's bodily relics. Anuradhapura, one of the most sacred ancient Buddhist centres in Sri Lanka, remains an important local and international pilgrimage site today.

Sri Lanka, AD 1–500

British Museum 1898,0702.7; 1898,0702.8; 1898,0702.11; 1898,0702.9 and 1898,0702.10

Collected by Hugh Nevill (1847–1897), a civil administrator of the British colonial government in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and purchased in 1898 from his brother Ralph Nevill.

Image caption:

Thuparamaya stupa in Anuradhapura, northern Sri Lanka is thought to be the first stupa to be built on the island.

Photo © Jan Wlodarczyk / Alamy Stock Photo (ID F788TW)

Cultural exchange

Sculptures of snakes are found at Buddhist sites, where they function as guardian deities. Monks or pious merchants may have brought this carved limestone panel from India as a dedicatory object for a shrine in Sri Lanka. There were long-standing cultural and trading links between the island and India, especially between the coastal regions now known as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu in south-east India.

Sri Lanka, AD 400–500

British Museum 1898,0702.195

Collected by Hugh Nevill (1847–1897), a civil administrator of the British colonial government in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and purchased in 1898 from his brother Ralph Nevill.

Links across the water

Small devotional images like this gilded bronze statue (4) were easily transported between Sri Lanka and India, leading to the exchange of artistic ideas. A distinctive feature of Buddha images from both Sri Lanka and southern India, for example, is the flame-shaped ushnisha on top of his head, representing his enlightenment.

4

Sri Lanka, AD 800–900

British Museum 1898,0702.29

Collected by Hugh Nevill (1847–1897), a civil administrator of the British colonial government in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and purchased in 1898 from his brother Ralph Nevill.

Image caption:

An image house at Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka containing a large stone sculpture of a seated and meditating Buddha, guarded by snake deities either side of the steps.

Photo © Matthew Williams-Ellis Travel Photography / Alamy Stock Photo (ID ERX3MA)

Panel on the left:

Buddhism in Sri Lanka

As geographical neighbours, religious ideas and devotional imagery flowed between India and Sri Lanka. According to the chronicles of Sri Lankan Buddhists, Buddhism was introduced to the island in about 250 BC by a delegation sent by the Indian king Ashoka. After this, some of the Buddha's relics were enshrined in stupas. A branch of the Bodhi tree, under which the Buddha achieved enlightenment, still flourishes where it was planted in the ancient city of Anuradhapura. Sri Lankan Buddhist art has its own distinct identity, such as the placement of monumental stone Buddha figures in image houses.

Film on the left:

Inner peace, 2025

Kim Lewis talks about her personal connection to Buddhism, and the inner peace her faith brings her, including visiting Buddhist temples. Like many members of the Thai-Buddhist community in the UK, every year Kim visits the Buddhapadipa Temple in Wimbledon, London with her family to celebrate Songkran, the Thai New Year.

The film is narrated by Kim Lewis. There are sounds of traffic, birds chirping, the wind blowing and Kim's footsteps. It is silent within the temple.

Length: about 90 seconds

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Hindu art

Panel on the right:

Hindu art

Hinduism covers numerous religious traditions, which share diverse beliefs, philosophies and practices that have evolved throughout India over thousands of years. Predating Jainism and Buddhism, its spiritual foundations are shaped by sacred texts such as the Vedas, Upanishads, Ramayana and Mahabharata. Many Hindu teachings emphasise the four aims of life – dharma (righteous duty), artha (prosperity), kama (desires) and moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth). Hindus care for images of their deities in daily rituals, believing them to be inhabited by the living presence of the divine.

Hindu art centres on representations of gods, who have long been represented symbolically and venerated through natural features found in the landscape. About 2000 years ago, they also began to be depicted in human form, incorporating some earlier nature-spirit imagery with additions, such as multiple arms to hold specific sacred objects. At about the same time, the first brick, stone and wooden temples were being constructed to house images of Hindu deities.

Central plinth:

Rescuing the earth from disaster

Vishnu has many different avatars. These are the bodily forms he adopts on earth. Varaha, the boar-headed deity, is his third avatar. Here, Varaha is shown with the goddess Bhu – the personification of earth – on his shoulder, having rescued her from the cosmic ocean where the anti-god Hiranyaksha had hidden her. Varaha's pose in this red sandstone sculpture was possibly inspired by the sight of wetland-living wild boars throwing up clods of earth with their tusks, searching for tubers.

Uttar Pradesh or Madhya Pradesh, India, AD 400–500

British Museum 1969,0616.1

Purchased in 1969 from dealers Spink & Son Ltd.

Funded by the Brooke Sewell Permanent Fund.

Image caption:

Painted between 1700 and 1710, this scene shows Varaha rescuing the goddess Bhu from the cosmic ocean. Perched on his tusks, she is represented as a fragment of the earth.

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Vishnu's avatars

These paintings depict nine of Vishnu's ten bodily forms on earth. Artistic representations of them have changed little over the centuries. Hindus believe Vishnu uses the different incarnations to preserve order on earth and to save the world and humankind from disaster. His first form is Matsya the fish, who rescued the first man from a great flood. Here, Vishnu emerges from Matsya's mouth. Rama, Vishnu's seventh avatar, is a central character in India's epic poem the Ramayana. Here, he stands in the middle of the scene holding a bow and arrow to defeat the malevolent being Ravana.

Deccan and Jaipur, India, about 1800

British Museum 1940,0713,0.25 and 1940,0713,0.27-34

Collected by Major Edward Moor (1771–1848), probably while serving in the East India Company army.

Donated in 1940 by Mrs A.G. Moor.

Panel on the plinth to the right, extreme left:

Vishnu and Shiva have many forms

Along with the goddess Devi, the gods Vishnu and Shiva are recognised as principal deities within the different Hindu traditions. Hindus believe Vishnu preserves order on earth and that he has 10 different avatars – bodily forms – to save the world and humankind from disaster. Also depicted in different ways, Shiva is often represented in his symbolic form as the phallus-shaped linga. Representations of Vishnu and Shiva incorporate elements from nature spirit imagery, including a frontal pose with one hand raised in blessing.

Image caption:

Map showing the places where many of the devotional images in this part of the exhibition are from with modern-day country and regional names for context.

Powerful symbols

The symbols of both the gods Vishnu and Shiva are engraved into this small garnet seal (centre). The conch shell and discus weapon represent Vishnu, while the central trident – a three-pronged spear – denotes Shiva.

India, AD 200–500

British Museum 1892,1103.134

Collected in 1887 by Major General Sir Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893), a British Army engineer and scholar, who founded the Archaeological Survey of India in 1861.

Donated in 1892 by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826–1897), former Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography at the British Museum.

Footprints and fossils

Hindus have long represented the divine symbolically. This sandstone plaque has a conch shell and club carved on its left and right sides. They help devotees identify the footprints as belonging to Vishnu, the god who preserves order on earth. They believe the fossilised ammonites found in the Kali Gandaki River in western Nepal are naturally occurring forms of Vishnu, symbolising a chakra – his discus-shaped weapon. This ammonite (right) has a carving of Vishnu reclining on the cosmic serpent Ananta Sesha.

Plaque, Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, AD 1700–1800

British Museum 1890,0805.4

Donated in 1890 by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826–1897), former Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography at the British Museum.

Fossilised ammonite, Kali Gandaki Gorge, Nepal

British Museum 2017,3038.67

Donated in 2017 by the Simon Digby Memorial Charity.

Image caption:

The fossilised ammonites found in the Kali Gandaki river valley are called shaligrams – Sanskrit for 'sacred stones'.

Image © The Trustees of the British Museum

Image caption:

The Kali Gandaki River in Nepal, where fossilised ammonites are found.

Photo © Alexei Fateev / Alamy Stock Photo (ID 2A8TDW8)

Vishnu the protector of humankind

Although this sandstone sculpture is damaged, the figure can still be identified as the Hindu god Vishnu. This is because he wears a tall crown and has a garland draped over his arms. He would have held a club, conch shell, discus and spherical earth. These symbols were originally associated with Vasudeva-Krishna, a Hindu clan-deity from the Mathura region of northern India. These attributes were absorbed into Vishnu-related imagery when the two gods became linked.

Uttar Pradesh or Madhya Pradesh, India, about AD 450

The Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford EA1996.77

Purchased in 1996 with the assistance of the Art Fund, the Friends of the Ashmolean Museum and the MLA/V&A Purchase Grant Fund.

Panel:

A moment of transformation

Images of Hindu goddesses have many features in common with those of female nature spirits, including floral headdresses, plentiful jewellery and full figures. During the first century AD, an important moment of artistic innovation occurred when deities began to be shown with multiple arms. Each hand was held in a particular gesture or carried something which enabled the devotee to identify the god.

Goddess with many arms

This early image of a now unknown four-armed goddess is cast in copper alloy. Two of her arms are broken at the shoulders and her face worn smooth in veneration by devotees. Like other images of yakshis (female nature spirits), she is full-figured, has flowers in her hair and wears extravagant jewellery, including a girdle around her hips. The holes in the sash on either side of the goddess were used to fix the terracotta plaque to a tree or flat surface.

Deccan, India, AD 1–100