See some of these badges in a free community-curated display in the Money Gallery (Room 68), from 3 February – 8 July 2025.

Book a place on a free volunteer-led tour exploring objects with LGBTQ+ connections.

Once pinned to lapels and backpacks, these badges are now records of defining moments in LGBTQIA+ history.

Badges can be incredible records of social history. These powerful visual signals are made and worn for all kinds of reasons: they can showcase your passions, who you are and what you stand for. LGBTQIA+* badges are intimately connected with the history of activism and queer identities. The LGBTQIA+ community cares, campaigns and comes together in moments of need, joy, and solidarity and these times have often been marked by the creation of badges.

The British Museum has about 400 badges and pins associated with LGBTQIA+ movements and identity in its wider collection of 13,600 badges. The earliest badges in the collection date from the 1970s and most of them tell British stories. The badges mirror the periods in which they were made and are an invaluable source of social history for the LGBTQIA+ community, recording and honouring the progress made in the fight for equality and highlighting the hurdles yet to overcome.

In 2024 the British Museum invited four community partners and four volunteers who lead LGBTQ+ tours at the Museum to explore the LGBTQIA+ badge collection and co-curate a new display. Working together, the group organised the display according to certain themes, including solidarity, campaigning and activism within the LGBTQIA+ community. This community-curated display opened in the Money Gallery (Room 68) from 3 February – 8 July 2025.

Below, members of the co-curation group highlight four badges from the British Museum collection, and reflect on what they mean to them.

* Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual and other identities.

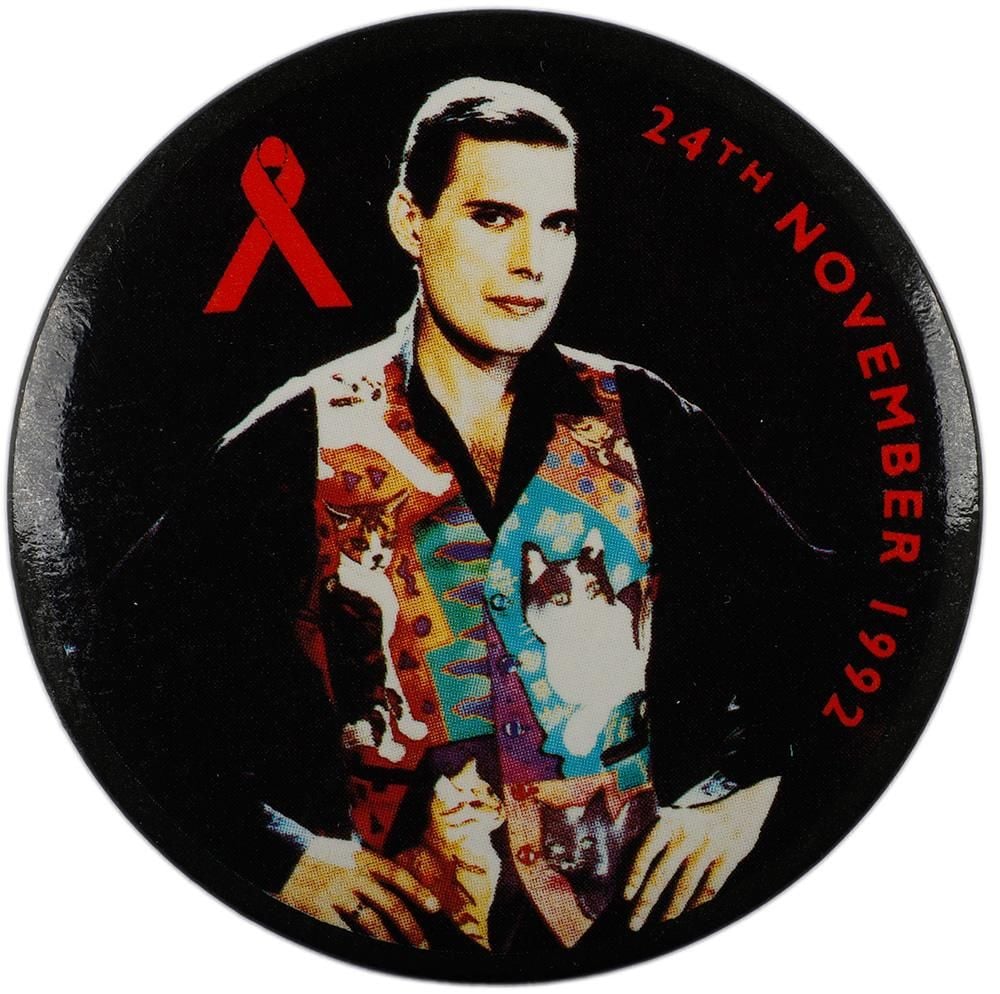

Freddie Mercury

by Eric Huang

Growing up, a Frankie Says Relax badge was always pinned to my jacket. The badge was dangerous. It pissed off my parents and proclaimed that I wasn't a 'normie'. A Pete Shelley badge for his gay anthem Homosapien, B-52's pins of the enormous drag queen wigs they often wore, and a masculine-presenting Annie Lennox leering like a Vegas bookie. These badges allowed me to express an identity I was still pondering, and do so safely because they could be passed off as a declaration of fandom rather than of sexuality. Or so I hoped.

The Mercury badge with an AIDS ribbon in the British Museum collection functions on these levels. It was created to mark the anniversary of the Queen frontman's death due to AIDS-related illness. On one level, it signifies a love for Freddie and Queen's music. On another, its very existence is political and an act of protest. Wearing it is activism, regardless of the owner's intention or awareness.

It was with this ignorance that I also wore a badge featuring artwork from the out and proud band Bronski Beat. I thought nothing of the pink triangle graphic until my English teacher explained its meaning to me: it was a symbol of gay pride reclaimed from its historical use to oppress queerness. The badge was gay – by wearing it, I was outing myself! I immediately took it off, but I couldn't stop thinking about it.

When I started at a new school in autumn, I re-pinned the Bronski Beat badge onto my backpack, situating it between a badge showing heavily eye-linered Depeche Mode and a badge of Bananarama surrounded by muscle-boy dancers. Coming out was years away, but with these badges on display, I started high school asserting a more confident me.

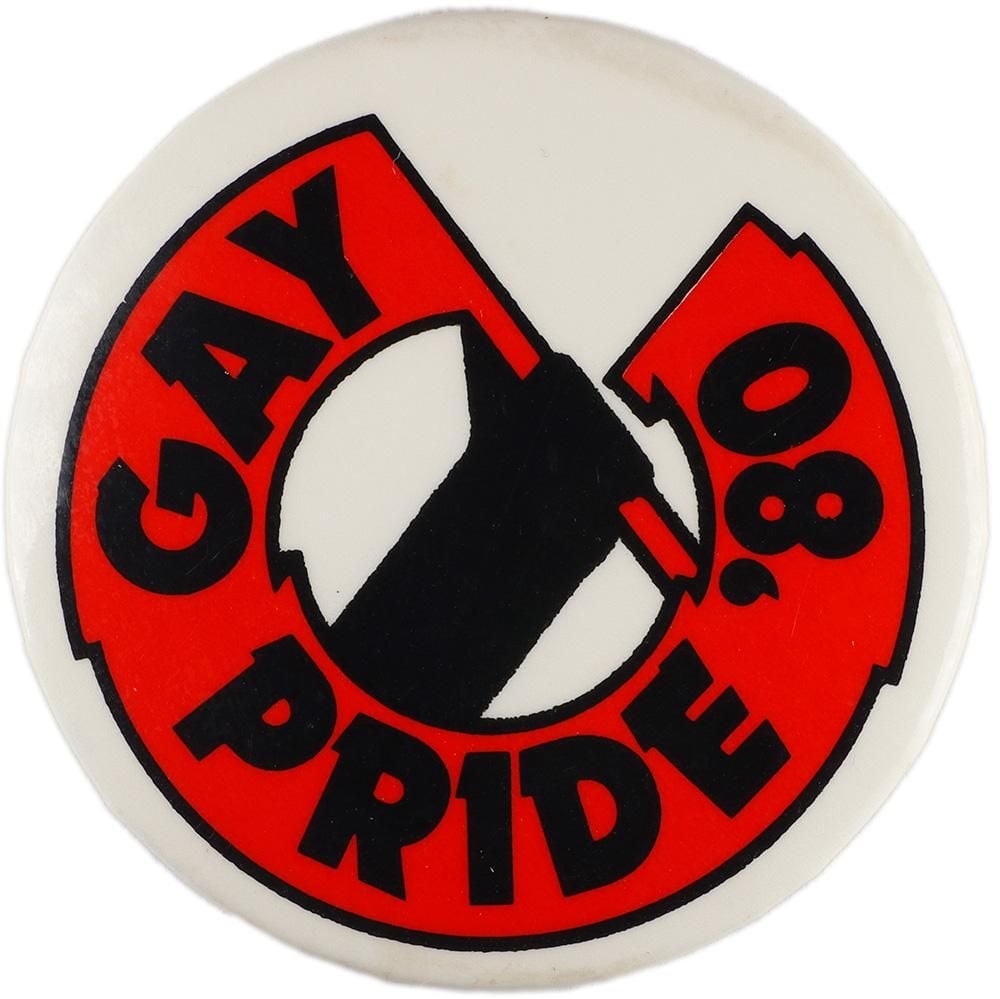

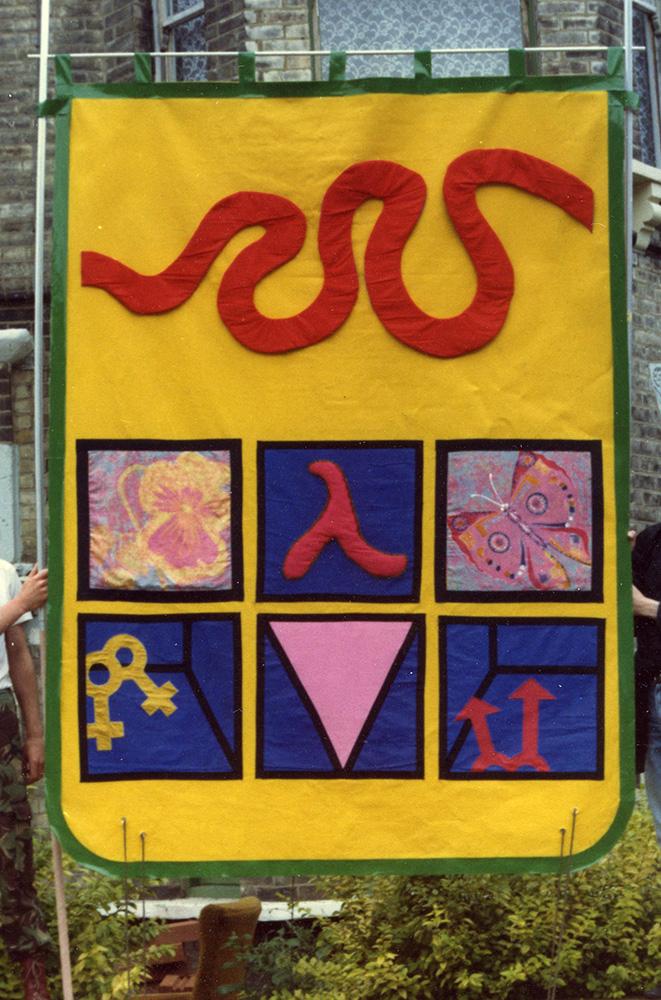

1980's Pride: A Badge and a Banner

by Peter O'Hanlon

This badge, celebrating Gay Pride 1980, was the winner of a competition promoted by Gay News. Gay Pride in the UK first took place in 1972 and was timed to mark the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in 1969. With its dynamic forearm raising a flag, or banner, it speaks of action; of solidarity; and of course visibility. I would surely have worn the badge during that year's march – my first Pride.

1980 would be a challenging year. I was new to London, I was gay, I barely knew anybody, and I wanted to connect. A listing in the media led me to a collective of gay artists, men and women, who had come together for an exhibition to mark that year's Pride. It would change my life. The exhibition was held jointly between The Oval House and the LGBT bookshop, Gay's the Word. I was one of the exhibitors and was responsible for the image on the promotional poster for the show. Together, the group designed and produced a banner for that year's Pride Parade, borrowing from the traditions of Britain's mining communities, and we marched with it through the streets of London and Manchester. The experience was thrilling and sometimes alarming: a heavy presence of police felt provocative but, faced with occasional expressions of public hostility, reassuring too – no matter, I was no longer alone. At the end of those unforgettable days my badges would disappear from view, out of sight of family, and colleagues, until it was safe to wear them with pride once again.

This blog entry is dedicated to those who with myself made the banner and marched with it: Bruce, Robert, Linda and Sue.

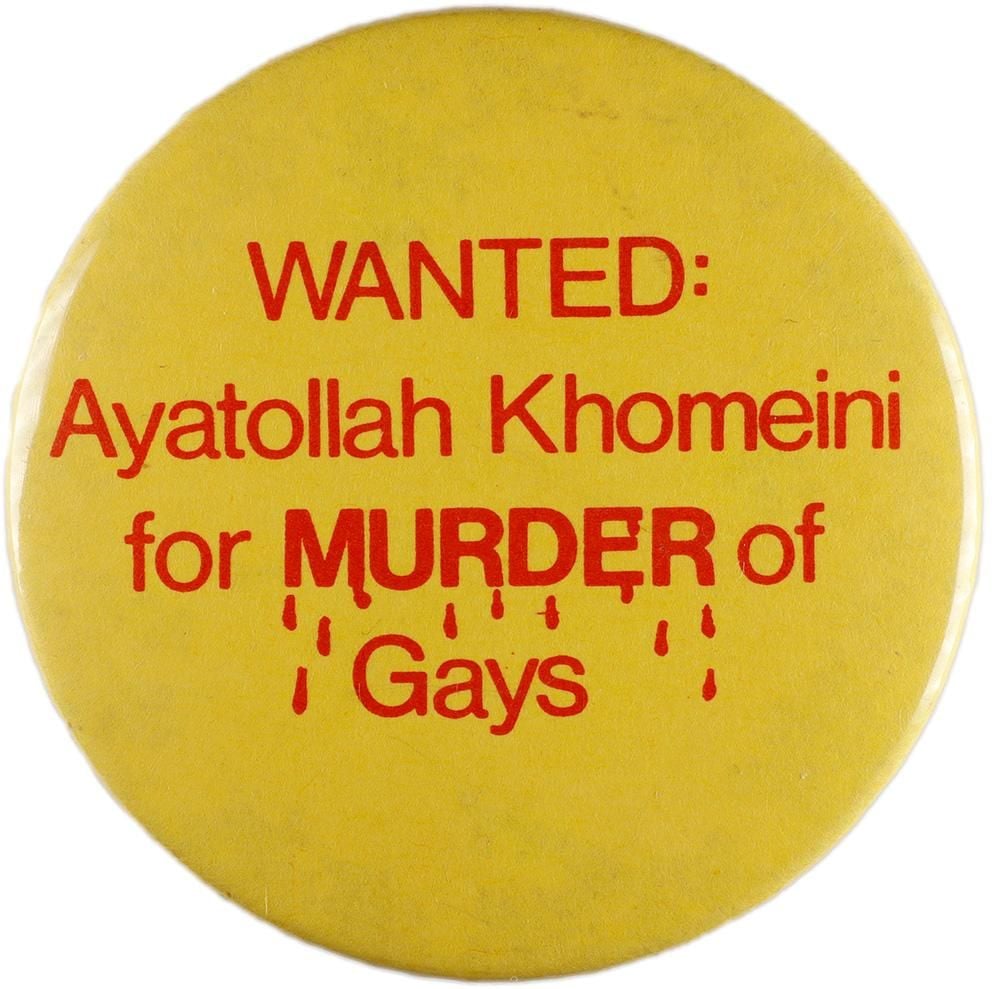

WANTED: Ayatollah Khomeini for MURDER of Gays

by Michele Facchinelli

In many countries around the world homosexuality is against the law. In some, it's even punishable by death. This badge refers to the killings of gay men in Iran during the 1980s under the rule of the former Supreme Leader of Iran, Ruhollah Khomeini.

The badge speaks to me on many levels. First, it's a reminder that despite all the progress we have seen in the UK and other Western countries, homosexuality and other queer identities are still threatened in many parts of the world, whether with death, jail or widespread discrimination.

Second, it reminds me of the power and resilience of the LGBTQIA+ community, which has fought for its rights and has endured despite persecution and prejudice. The discrimination that is happening around the world used to happen in countries where gay rights are now protected by law. And we must continue to protect those rights even when they are enshrined in law. As António Guterres, UN Secretary General, said in 2023: 'we cannot and will not move backwards.'

Third, it also speaks to me about the support within the community. This badge was probably worn by protesters in London fighting for the rights of people on the other side of the world. It's inspiring to see people come together on common beliefs and fight for people they may have never met before.

I am very grateful to have been able to contribute to this badge display project. I find it incredible how a simple badge can evoke such a diverse range of feelings. A small object with so much history, culture, suffering and joy behind it.

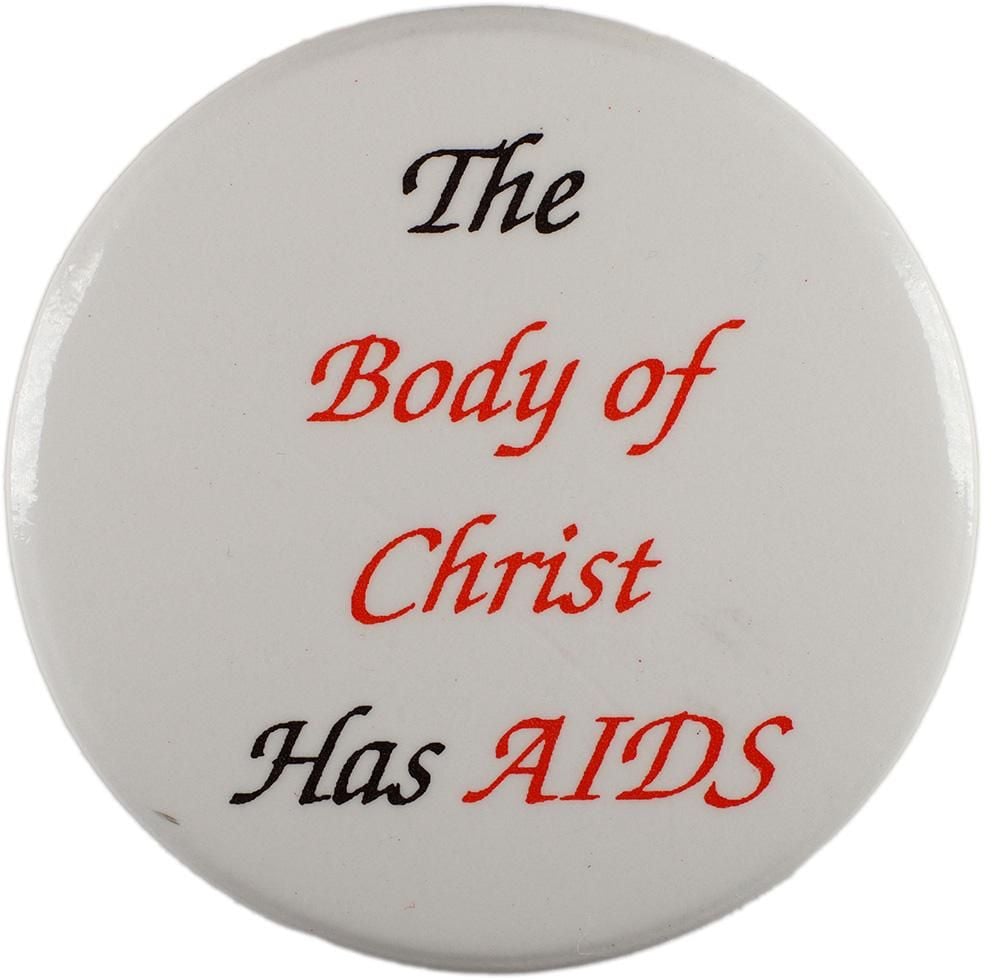

The Body of Christ has AIDS campaign

by Alex Pilides

Historically, social views around AIDS focused on the lifestyles of those who contracted it and how it was passed on, and as a result HIV and AIDS were initially often associated with homosexuality and the LGBTQIA+ community. Some members of the Christian community connected HIV and AIDS with sexual deviance and immorality. However, since the 1980s AIDS and HIV have impacted, and continue to impact, many African populations the most, regardless of the sexual orientation of those who have contracted it.

In order to rally the Christian community and to receive international support, particularly from Christian communities in the United States and Europe, African theologians in the 1980s and 90s encouraged campaigns like 'The Body of Christ has AIDS'. The aim of the campaign was to evoke compassion and empathy, highlight the crisis as a humanitarian one, and contextualise it within a Christian context. It's a powerful statement that highlights the relationship between the Church, the people and the Body of Christ, and therefore that there is a duty of care for the Church to support those living with AIDS and HIV. This campaign challenged the Western world to show solidarity with all regions of the world and all people affected by HIV.

This slogan was similarly used by Marsha Stevens, an American Christian singer, who was shunned by the Christian music industry after coming out as a lesbian in 1981. She joined a queer-affirming church and established an organisation, Born Again Lesbian Music. During the AIDS epidemic she released music campaigning for justice, including her 1995 song 'The Body of Christ has AIDS', which highlights how anyone can have AIDS and still deserves support. The history behind this badge reminds me of the wider geo-political and socio-cultural forces that continue to define global access to healthcare. Be it a badge, pop song or international campaign such as 'undetectable = untransmittable', destigmatising HIV and AIDS is just as important as the medical advancements that have saved lives.

The future of the LGBTQIA+ badge collection

The Museum acquired its first LGBTQIA+ badge in 1978. While the collection is extensive, it is not comprehensive. It reflects what has been donated by individuals and collected by curators, and it is weighted towards the UK rather than representing all parts of the worldwide LGBTQIA+ community. The Money and Medals department continues to collect these badges to ensure the full community is better represented, as well as contemporary campaigns and agendas.

This project was part of a wider community and volunteer research and engagement programme that the Museum runs year-round, which involves working with a diverse range of LGBTQIA+ community partners to research and creatively respond to the collection at the Museum.

See some of these badges in a free community-curated display in the Money Gallery (Room 68), from 3 February – 8 July 2025.

Book a place on a free volunteer-led tour exploring a fascinating selection of objects with LGBTQ+ connections. The tour ranges from the ancient world to the present day and includes some of the most famous artworks on display.

This display was supported by the E S G Robinson Charitable Trust.