Find out more about the redevelopment of Norwich Castle's iconic Norman Keep.

Find out more about the creation of the Gallery of Medieval Life: A British Museum partnership.

From seeing Valentine's Day as a time for romance to the idea of giving your heart to a lover, medieval culture influenced many modern ways of looking at love.

Images of courting and romance on medieval objects show how people at the time thought about love and reveal their continuing legacy. The objects featured in this blog will be on display in the Gallery of Medieval Life, a new British Museum partnership gallery due to open in Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery later this year.

A day for lovers

Have you ever wondered when Valentine's Day came to be associated with the concept of love? In the Middle Ages, 14 February was celebrated by the Roman Catholic Church as the feast day of Saint Valentine, but it wasn't until the 1300s that the date came to be connected to romance.

One of the first literary references in English is thought to be Geoffrey Chaucer's late fourteenth-century poem the Parliament of Fowls. In the poem the narrator has a dream in which he visits a temple of love and witnesses a debate among birds, overseen by the goddess of Nature. Three male eagles put forward their best arguments for why a particular female eagle is their choice of mate. Their pleas are unsuccessful, and the female eagle asks Nature to allow her to wait a year, after which she will make her own decision. This event takes place, as the reader is told, 'on Seynt Valentynes day, Whan every foul cometh there to chese his make' (on St Valentine's own day, When every bird comes there a spouse to take*).

Chaucer's poem explores the theme of free will in love and inextricably links the concept of choosing a partner with this date in February. It is the day to declare interest in a lover, whether it is reciprocated or not. More widely, Valentine's Day came to be observed across medieval Europe as a time for celebrating love.

Giving your heart

In the medieval period, jewellery, particularly rings, were popularly given as courtship gifts or presented as part of wedding ceremonies. Many surviving examples have romantic mottos. A fifteenth-century ring found in Lessingham, Norfolk, is engraved with one of the most common phrases found on medieval jewellery, 'De Bon Coer' which translates as 'Of Good Heart'. The idea of giving your heart to your loved one was widely depicted in medieval art, it was a sign of devotion, faithfulness and loyalty. The phrase 'of good heart' on this ring was perhaps an apt choice for a token of love or a wedding band, emphasising the wearer and giver's commitment to each other. The words are on the inside of the ring in a Gothic style-script known as Black Letter and filled with black enamel, to help the text stand out against the bright gold metal.

Medieval audiences understood the idea of a 'good heart' as being more than simply a phrase marking good intentions. At this time, the heart was viewed as the centre of emotions and it was during this period that the heart began to be portrayed in its now well-known form. Objects with the image of a heart, or naming the organ, evoked the idea of presenting your heart to another. Perhaps this fifteenth to sixteenth-century mount, from a cap hook or badge, was also a gift from a lover, as a symbol of their own heart. Found in Wereham, Norfolk, it is set with a triangular-shaped rock crystal, with a groove cut at the centre to form the heart's lobes. Around the edge is a joyful inscription in English telling the wearer to, 'Be Mery'.

Love as a flower that blooms

Plants and flowers decorated a variety of medieval objects and had a range of symbolic associations. May, for example, was traditionally seen as a time for courting, when nature was renewed and blossoming, and love might do the same. Because of this, illustrated medieval calendars often included an image for that month of couples within lush greenery. Although given as gifts since ancient times, the association of flowers with romance was particularly strong in the Middle Ages and continues to this day. On the Lessingham ring mentioned above, the outer surface of the hoop has flowers between two leaves within triangles divided by zigzags.

These flowers are stylised and although the medieval goldsmith who made the ring might not have intended to depict a specific plant, the splayed petals are reminiscent of oxeye daisies, also known as marguerites, shown in profile. Geoffrey Chaucer began another of his poems Legend of Good Women, with a description of flowers in a meadow stating that the daisy was his favourite of them all. In doing so, Chaucer was making a nod to the popularity of the name Marguerite in love poems of the fourteenth century. Although the original owner of this ring and how they came to receive it are unknown, could they also have been named Margaret in reference to the marguerites that decorate it?

Medieval women were often compared to flowers in literature and art. For example, this fourteenth-century silver seal matrix, a device for forming a wax seal, plays on the idea but has a dual meaning. At its centre is a woman, holding a book in one hand and the folds of her dress in the other. She is flanked by the letters I and A, probably the initials of the owner's name, and is encircled by an inscription. Written in French, it has been translated as, 'I am the flower of true love' or 'Of faithful love, I am the flower'. The text seems to directly refer to the woman as the symbolic flower of love, but it also refers to the wax seal itself. Seals in the medieval period were used to authorise documents and served as signatures for individuals and organisations. Therefore the seal, a mark of authenticity, was making a statement that it was the representation of blossoming love. Although we don’t know who the original owner of this matrix was, the message on their device would have been perfectly suited for a seal attached to a marriage certificate or a personal item of correspondence, the contents of which may also have represented 'true love'.

The 'thrill of the chase'

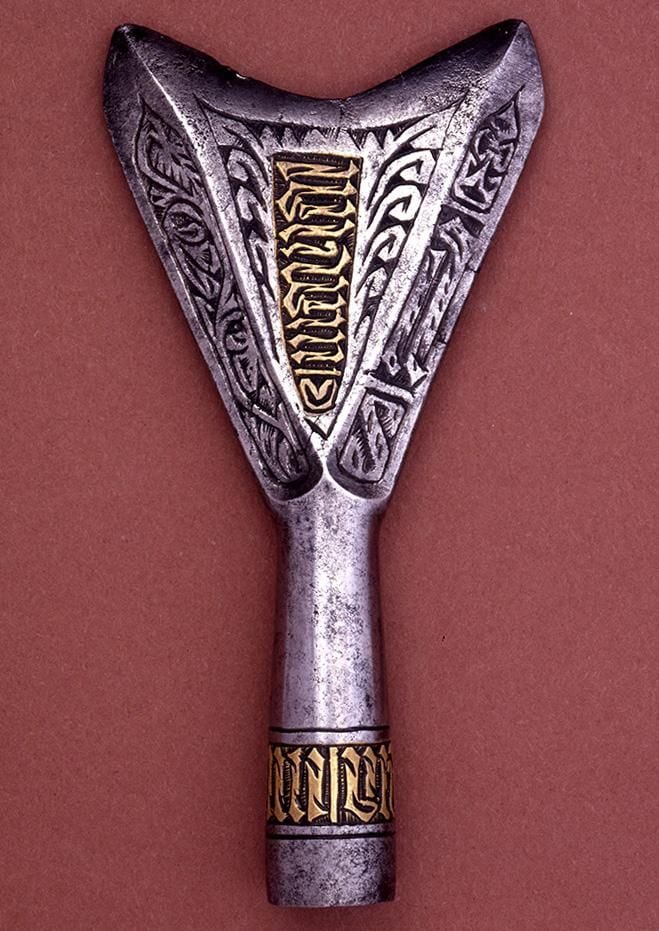

Medieval nobles loved to hunt. It was a popular form of elite entertainment that allowed the participants to demonstrate skill and prowess while socialising. An intricately decorated end of a crossbow bolt gives a sense of the more elaborate types of objects people used in hunting. Formed of steel, it has a hollow socket to fit onto the head of an arrow bolt. On both sides are intricate scrolling designs, the letters S and Y can be made out on one side and a text-like pattern is highlighted by bright gilding.

Hunting provided an opportunity for noble men and women to interact. It involved many people in addition to those who pursued the animals: there were spectators, people who participated in hunt feasts, as well as countless attendants. It is no surprise then that artistic and literary depictions of the 'thrill of the chase' connected romance to hunting.

The back of a fourteenth-century mirror case, a medieval form of a compact, depicts a genteel couple in the woods on horseback. It is a hunting scene that is also full of suggestive imagery. On the right is a man holding up his bird of prey with the reins of his horse in the same hand. He is turning towards the woman, his right hand reaching out behind her back to embrace her. The woman, the focal point of the scene, looks up to the man, smiling. She holds her horse's reins in one hand and has a whip in the other. Below their feet, a dog closely chases a rabbit in a further allusion to pursuit. Behind the couple are smaller attendant figures carrying spears. This was a widespread motif in the Middle Ages showing the power play of real and imagined courtship.

Mirror cases were part of ladies' cosmetic sets. The more affordable ones were made of copper alloy with circles of coated glass fixed inside. Expensive versions were made of ivory, such as this example. As items of toilette, mirrors were viewed as intimate objects and were often associated with love and sexuality, which might explain the show of affection carved on the back of this case.

Love as a game to play

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries in particular chess was frowned on by church leaders, but as it gained prominence in European courts it became increasingly admired as a game of skill and strategy that was played by both men and women. From its origins chess was a military strategy game, originating in India where the pieces represented the divisions of the army. When it later spread to Europe, the forms of the pieces changed to reflect the social setting of Western courts, bringing queens and bishops onto the board. Chess sets could be large and luxurious, with pieces carved in expensive materials such as rock crystal, jet and ivory.

Surviving pieces like this mounted bishop show that the forms and materials of these miniature sculptures were to be enjoyed by touch as much as by sight: measuring nearly ten centimetres high, it sits comfortably in the hand.

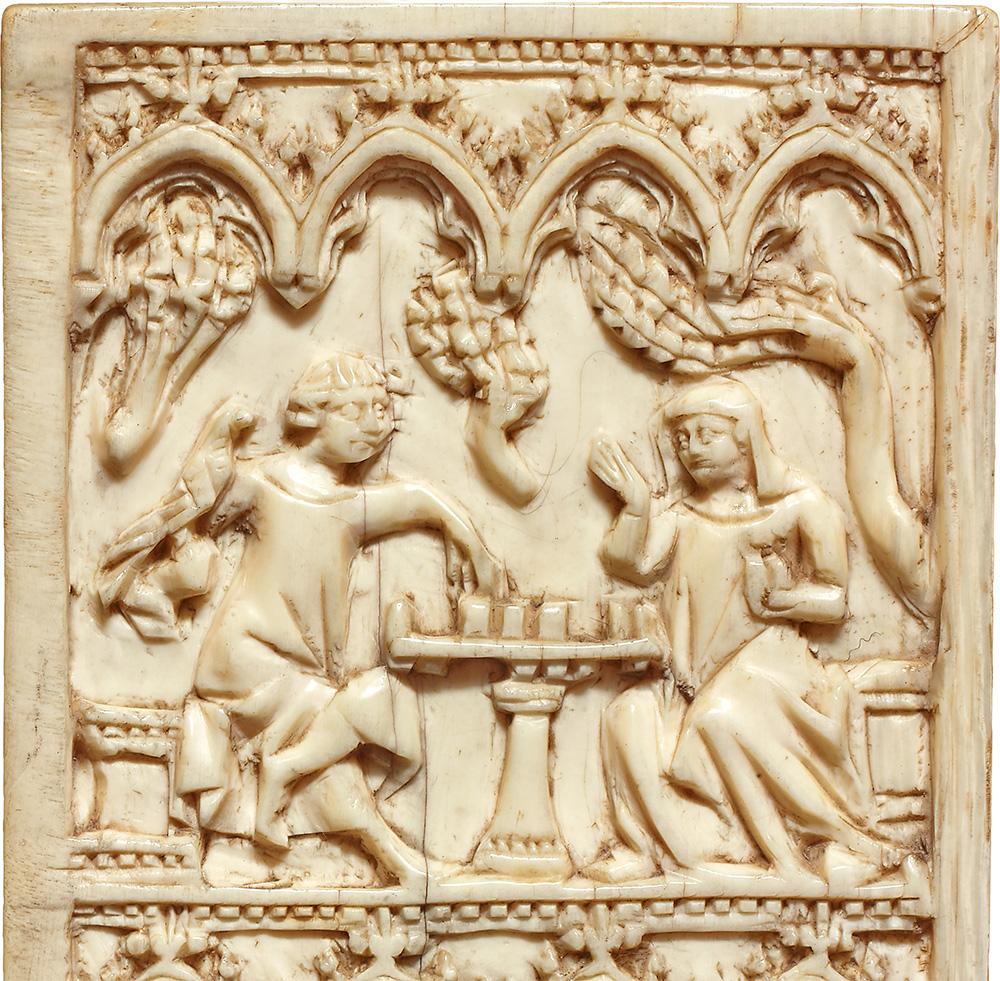

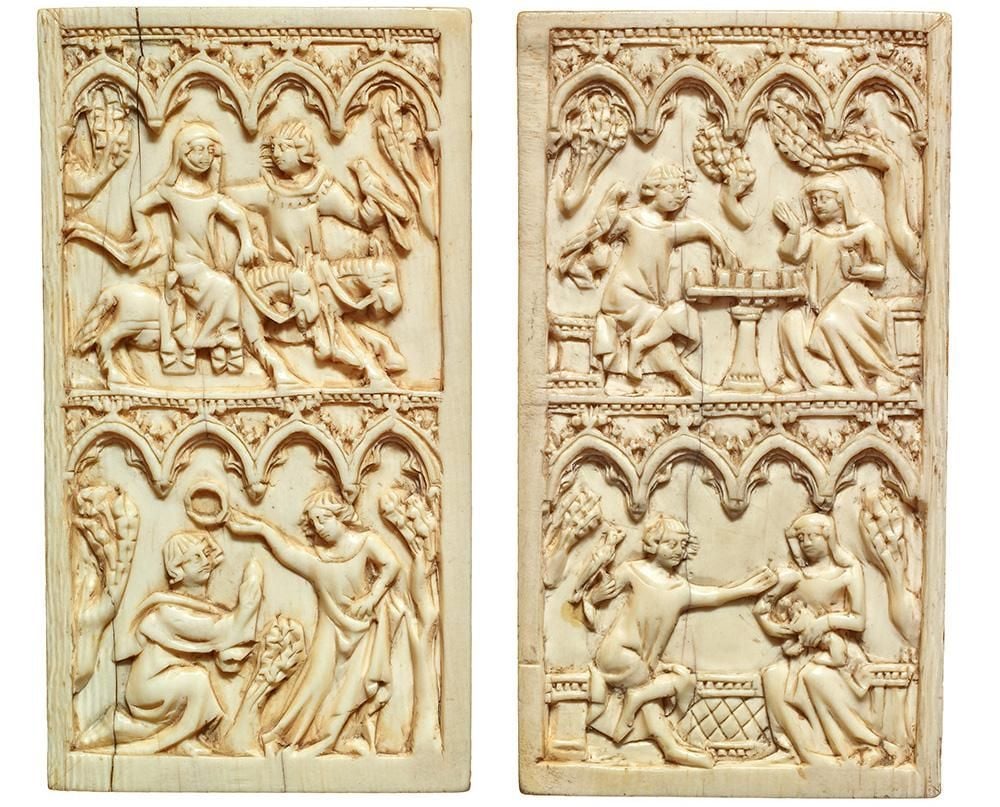

Playing a game of chess at court was a way for men and women to interact. As a game of skill rather than chance it gave both players an equal footing, as well as allowing women the rare opportunity to exert power over their male opponent. This battle of wits and wills was explored as an allegory of love in many medieval artworks and through literature, such as the late fourteenth-century French poem Les Échecs Amoureux where a courtly young man enters a garden to play chess against a woman. This idea of an intimate game, played within nature is visualised on a fourteenth-century writing tablet, which is a small ivory panel with a wax-filled recess in its back for writing on. Here a woman is shown having already captured two of her opponent's pieces in a chess match. The small size of the scene means that the exact pieces cannot be made out, but she holds them in her left hand to demonstrate her dominance in the game. Perched either side of a chess board set up on a table, the couple are animated. The woman gestures with a raised hand and the man reaches out to make his next move, his hand resting on a chess piece, while a bird of prey perches on his other arm.

Valentine's Day

This chess match is one of four images decorating a pair of panels. Below, the same couple are seated outdoors on a bench, the young man still has his bird of prey and the woman cuddles a dog on her lap. He is reaching towards her, probably in a gesture of affection known as chucking under the chin. On the other panel the couple ride on horseback, in a similar manner to the pair hunting on the mirror case, and beneath them the youth kneels in devotion as the woman presents him with a floral crown called a chaplet. Although the reality of medieval relationships could be very different, these scenes are popular tableaus of ideal courtship. If on 14 February you receive a card with a big red heart, a poem inspired by the symbolism of flowers, or a romantic declaration from someone offering you their heart, then you might just find that your Valentine's Day is more medieval than you think.

Find out more about the redevelopment of Norwich Castle's iconic Norman Keep.

Find out more about the creation of the Gallery of Medieval Life: A British Museum partnership.

* Geoffrey Chaucer, The Parliament of Birds, translated by EB Richmond (2004).