See the prints in the special exhibition Hiroshige: artist of the open road, opening 1 May 2025.

Join the curator of our new exhibition as we explore how Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) became one of Japan's most talented, prolific and popular artists.

Introduction

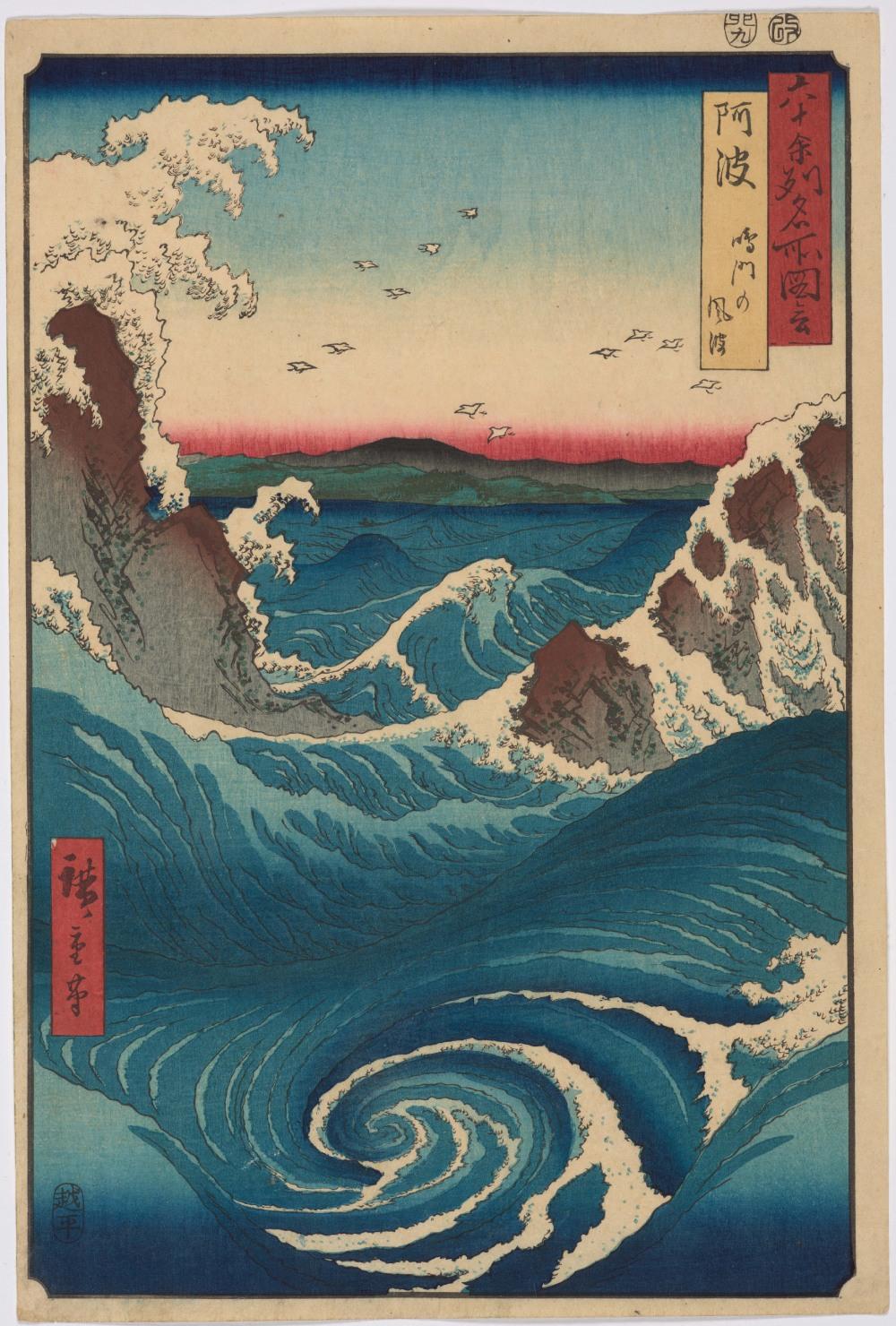

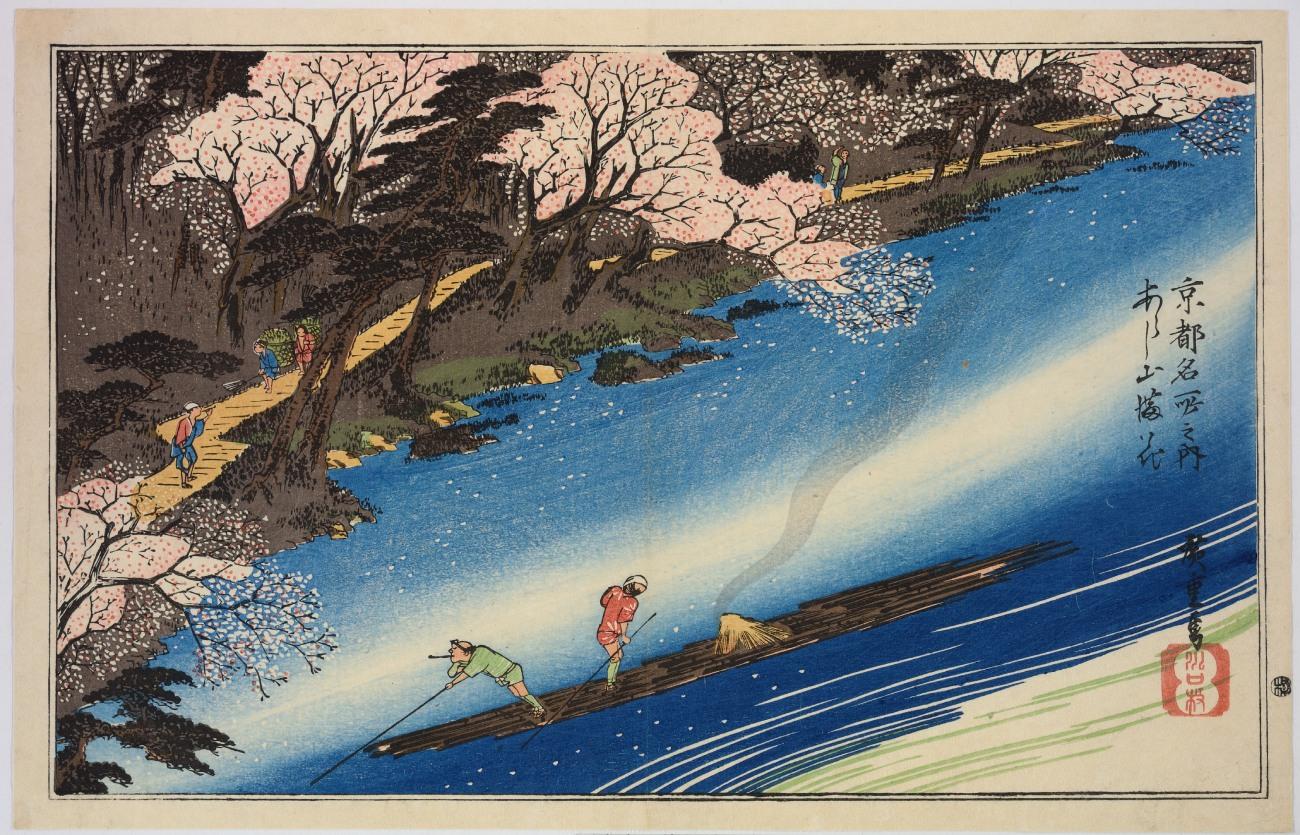

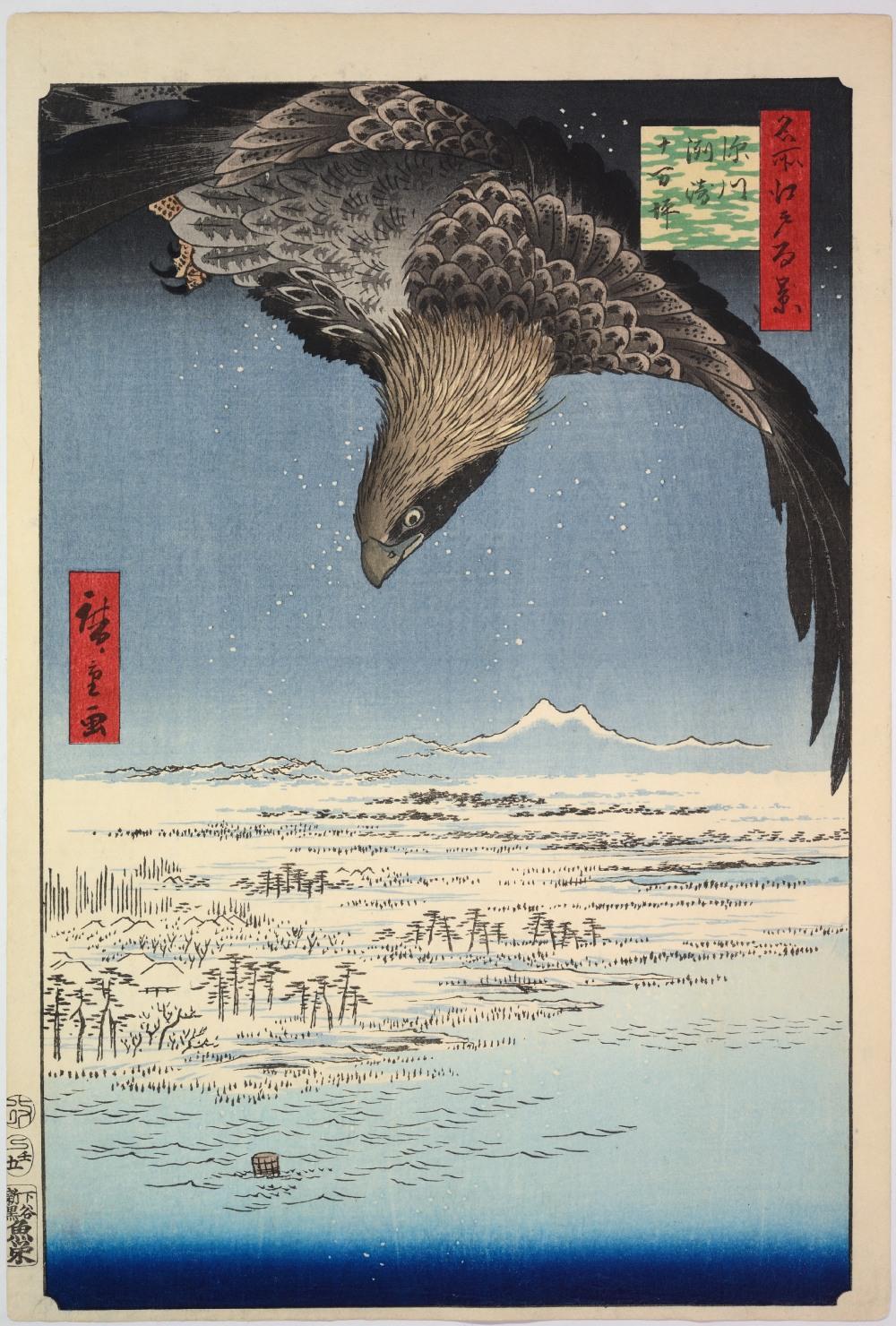

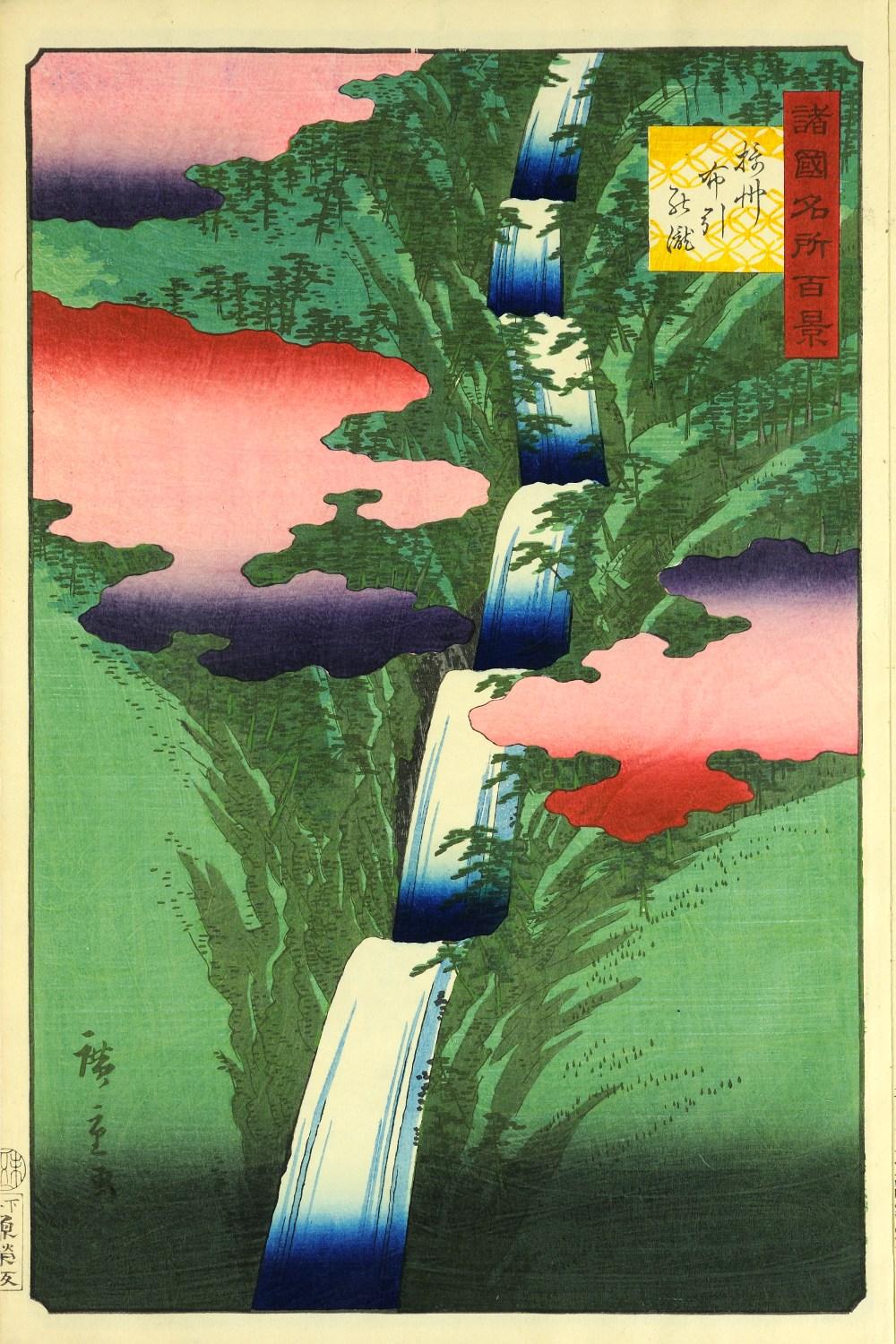

Born into a samurai family during an unsettled time in Japanese history, at the turn of the 19th century, Hiroshige created a serene vision of daily life that won popular acclaim in his own day and has remained influential ever since. His subjects range from fashionable figures and inviting city scenes to calm landscapes and lively studies of plants and animals. Hiroshige's work spoke to a contemporary fascination with domestic travel, and he captured the rhythm of life on the road perhaps more vividly and prolifically than any other artist of his time. His facility with the brush and skill as a colourist underpinned his thousands of prints, hundreds of paintings and dozens of illustrated books. Consulting closely with his publishers, block-cutters and printers, he achieved special effects that give his printed work the appearance of miniature paintings, notably the subtle gradation (bokashi) for which he is particularly known.

Becoming Hiroshige

Hiroshige was born Andō Tokutarō, the son of a low-ranking samurai retained by the ruling Tokugawa family in Edo (present-day Tokyo). For generations the Andō family had held the hereditary position of 'designated fire warden' (jōbikeshi-dōshin) in the Yayosu (or Yaesu) fire brigade east of Edo Castle and were closely tied to the safety and security of the shogun and his government.

Tokutarō demonstrated an early aptitude for painting but seems to have had no access to the shogun's painting academy, the Kano school. Motivated perhaps by curiosity and the chance of a supplementary income, which many low-ranking samurai needed to support their families, he crossed status boundaries and sought out studios associated with the world of popular culture, known as the Floating World. Around 1811 he applied to train under two prominent Floating World artists, Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769–1825) and Utagawa Toyohiro (1773–1829), both of whom promptly rejected him. Undaunted, the young aspirant applied once more to train under Toyohiro, who relented and gave him a place in the studio. Toyohiro's understated approach to popular subjects evidently agreed with the new apprentice, for only a year later, the formerly sceptical Toyohiro granted him an artist name, given by a master to recognise a student's talents. The name was Hiroshige, combining the '-hiro' of Toyohiro with the first character of Hiroshige's given name at the time, Jūemon, using a Japanese-style pronunciation ('shige') for that character. More than a decade of designing pictures of beautiful women and actors – the standard fare of the Floating World – would follow before Hiroshige turned his hand to landscapes.

Picturing the open road

Hiroshige travelled widely and in the preface to his last illustrated book, One Hundred Views of Fuji (posthumously published in 1859), explains that his drawings present 'views that I had before my very eyes and took down exactly as I saw them' and that while 'abridged in many places, they show entirely true-to-life landscapes, in order to give others a few moments of pleasure without the inconvenience of a long journey'. Notes in his surviving travel picture-diaries on all-night drinking parties, the quiet refinement of an unadorned home in the provinces and remarkable people, such as a samurai-swordsman who demonstrated how to draw a longsword from a seated position, show Hiroshige to have been sociable, interested in the world around him and open to the small adventures that travel sometimes affords. They indicate that even when not based on direct experience or literal fact, his landscape views were rooted in a true and sympathetic understanding of the land and of life on the open road.

By far the most important highway of his day was the Tōkaidō (Eastern Coast Road), which ran for 500 kilometres (300 miles) along the south coast of Japan's main island of Honshū through 53 stations to link Edo, the Tokugawa shogun's military base, with the emperor's city of Kyoto. European visitors who saw the Tōkaidō in the early 1600s admired its breadth and clean condition, the evenness of its surface maintained with sand and gravel, the engineering of the passes cut through mountain ridges and the sheer numbers of people moving along its length. In keeping with this highway's social and cultural significance, Hiroshige devoted more than 20 different print series to the Tōkaidō, amounting to roughly 700 prints, or 15% of his output.

Another major route was the steep and often treacherous Kisokaidō (Kiso highway; also called the Nakasendō or Central Mountain Road), which linked Edo and Kyoto via 69 stations through the mountains northwest of Edo, now called the Japanese Alps. Hiroshige produced only one series on the Kisokaidō, but he seems to have found the novelty inspiring, as it includes several of his most engaging designs.

Towards the end of his career, he produced the innovative 100 Famous Views of Edo (1856–58). In discussing this series, which experimented with different angles of view and strikingly juxtaposed enlarged foreground details with distant landscapes, the poet Tenmei Rōjin (1781–1861) observed that the pictures 'seem to place the landscapes before our very eyes'.

Hiroshige meant his pictures to take the viewer on a vicarious journey away from the stresses and strains of everyday life (which he had known in his youth) to places that, in his hands, appear more dignified, permanent and real than the worlds we ordinarily inhabit.

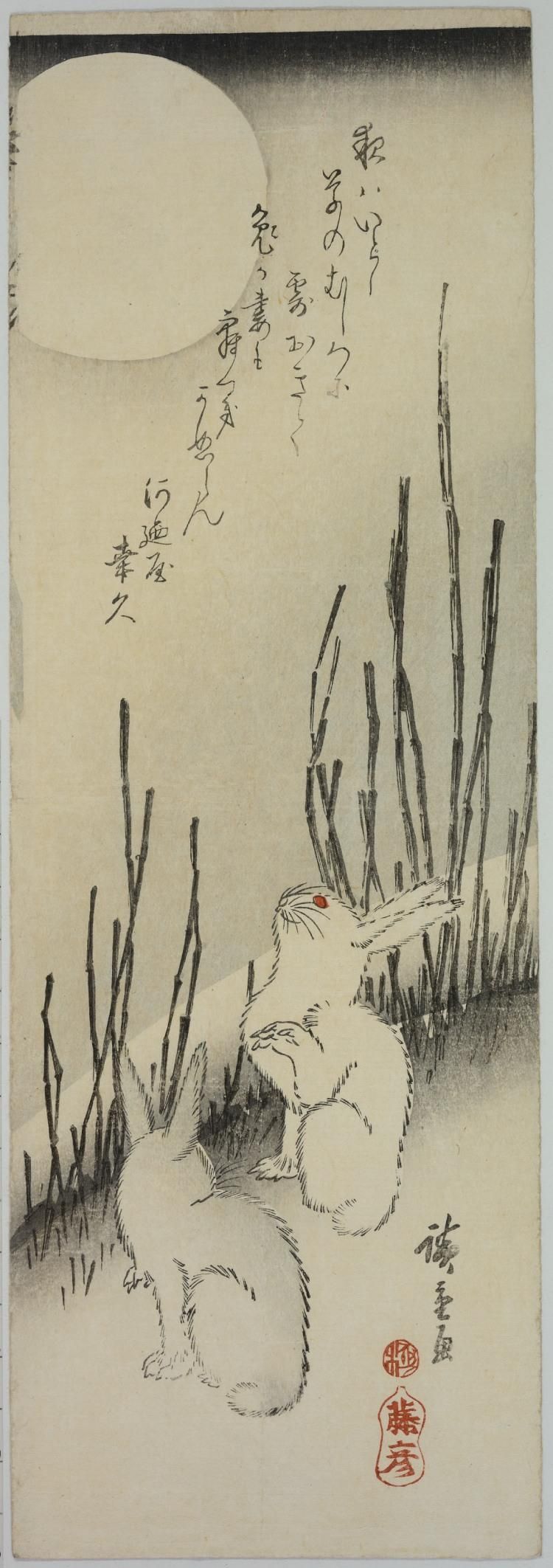

Nature all around

In a similarly idealised way, Hiroshige's nature prints harmonise plants, animals and poetic inscriptions in an expression of classical Japanese poetic thought. Each design opens a window onto a tranquil time and place where nature, poetry and painting meet. The effect is achieved partly through the graceful layout of the poems and the varied styles of calligraphy in which they are written, but equally important is the elegance that Hiroshige lends to his representations of the natural world.

At the same time, Hiroshige's nature prints invite us to reflect on the astonishing craft that converted his brushed designs into the medium of the woodblock print, as well as the role of the publisher in managing production and sales. The majority have a tall, narrow format recalling the tanzaku, a type of traditional Japanese paper used to record poems. For example, in the short span between around 1832 and around 1835, Hiroshige delighted the print-buying public with 22 large tanzaku (ō-tanzaku) nature prints designed for Wakasaya Yoichi (Jakurindō), and forty medium tanzaku (chū-tanzaku) prints designed for Kawaguchiya Shōzō (Shōeidō).

For each print design, Hiroshige prepared a detailed outline drawing on thin paper (hanshita-e, or 'block-ready drawing'). After it had received the approval of a government censor, the drawing went to the master block-cutter. This skilled craftsperson, with a decade of training, pasted it face-down onto a block of mountain cherry wood, cut along either side of the outlines, staying faithful to the rhythm of the artist's brush, and then chiselled away the unwanted areas in between to produce the key block (omohan). The printer, too, required a 10-year apprenticeship, to attain complete knowledge of the preparation of pigments, and the changes wrought by pigment on wood and paper. Apprentices also trained for years to master the hand-held printer's pad (baren), a round lacquer disk wrapped in bamboo leaf, which transferred pigment to paper and brought out the special effects cut into the blocks or indicated on the artist's proofs. No mechanical press was involved. The effects included gradation, embossing (kimedashi) and engraving (karazuri).

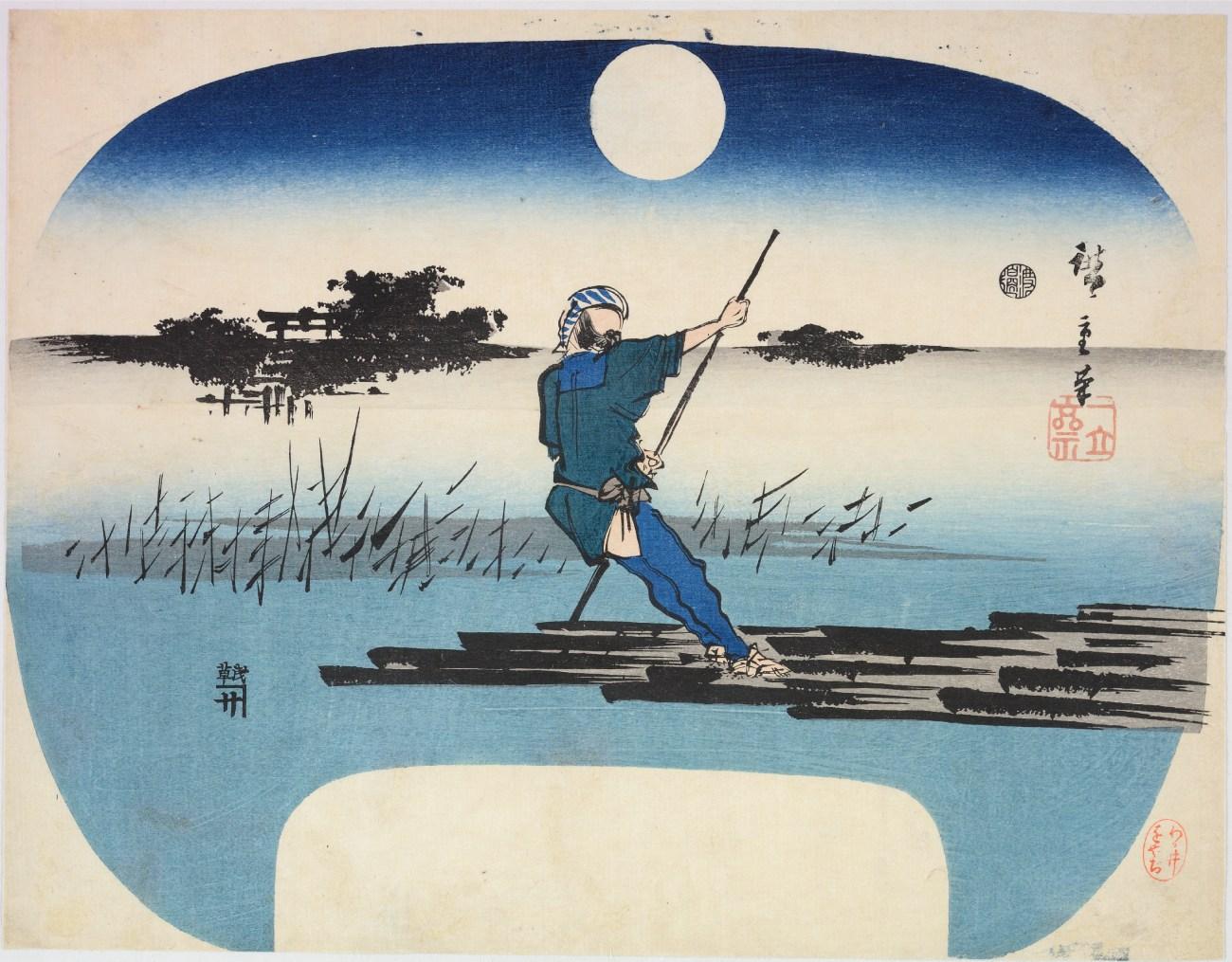

Catching a summer breeze

Warm summer weather saw a rising demand for inexpensive, hand-held printed fans that could be bought on the spot during a festival or an evening's stroll along the river, enjoyed for a few hours or days and then discarded. From around the late 1700s to the end of the Edo period (1615–1868), by far the most popular format for this type of fan was the ovoid uchiwa. Unlike the compact folding fan (ōgi), uchiwa were pasted flat onto a framework of fixed bamboo ribs. With an engaging picture facing front and a plain design concealing the ribs on the reverse, they were beautifully made objects that could be used to refresh oneself while impressing others.

The statistic is regularly adjusted upwards, but researchers currently think that, starting in the mid-1830s and continuing for more than 20 years, Hiroshige designed close to 600 uchiwa, far more than any other artist. Many are known today only in unique examples, and on this basis, a recent estimate places his actual output at closer to 1,000 designs. Two-thirds of Hiroshige's uchiwa designs illustrate famous places (meisho), but since summer pleasure-seekers generally took the refreshing evening air (yūsuzumi) alongside streams, ponds and coastal areas, Hiroshige particularly featured bodies of gently flowing water in this category. He also made effective use of Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment that became available in Japan on a commercial scale from the late 1820s. His monochrome blue pictures (aizuri-e) have the cool refinement of ink paintings and Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. Held as they were close to the heart, Hiroshige's uchiwa prints may have instilled a feeling of personal connection with him as an artist – and helped to turn his artistic insights into a shared way of seeing the world.

Hiroshige's legacy

Throughout the last 20 or so years of his life, Hiroshige's prints ranked among the most celebrated in Japan. Yet, despite his seemingly unshakable commercial success, he reportedly sought frequent loans to maintain his house and for other outgoings, and on the sixth day of the ninth month in 1858, he died a debtor. His will reveals cloudy hesitations and misgivings over his finances and how to acknowledge his samurai heritage, lending an unexpected complexity to our picture of Hiroshige as an individual. This stands in striking contrast to the clarity and certainty of his artistic style, which seems designed to lift others above and beyond the murk of human affairs, towards a brighter view of the world as he imagined it could be. This vision finds its final, concise expression in his elegant and widely circulated 'death poem', a prayer for rebirth in the western paradise of Amida Buddha:

I entrust my brush

to that highway heading east

and seek journey's end

in the celebrated sights

of a pure land in the west.

His two leading students, Hiroshige II and Hiroshige III, both diligently followed their teacher's style, as though recognising that his steady approach would be needed more than ever in the tumultuous transition to the Meiji era (1868–1912).

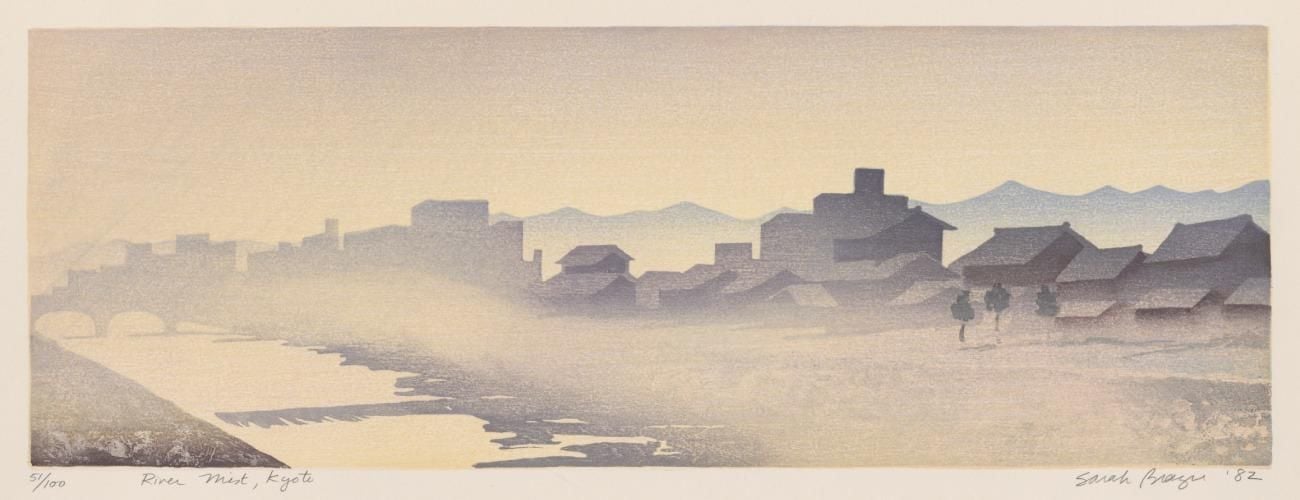

Hiroshige's global impact since his death is evident in the work of Whistler and in particular of Van Gogh, who collected his prints and based his own pictorial experiments upon them.

And Hiroshige continues to inspire modern and contemporary artists, as seen, for example, in Koya Abe's (b. 1964, Japan) and Emily Allchurch's (b. 1974, UK) digital interpretations of his more celebrated designs, Sarah Brayer's (b. 1957, US) atmospheric use of gradation, Noda Tetsuya's studies of daily life, and Julian Opie's (b. 1958, UK) mesmerising lenticular printed landscapes.

Conclusion

Hiroshige's calm artistic vision of Japan connected with people at every level of society, as demonstrated by his popularity in his lifetime. This exhibition marks a milestone, as the first exhibition at the British Museum to focus solely on Hiroshige, and the first in London for over 25 years, and we hope that visitors are just as captivated by his work today as they were in Edo-period Japan. It celebrates a major gift of 35 prints by Hiroshige from the collection of Alan Medaugh to the American Friends of the British Museum and features significant loans from Mr Medaugh and other international and UK lenders.

See these works alongside other prints, paintings, books and sketches in Hiroshige: artist of the open road, which opens 1 May 2025. Book early bird tickets now for at least 20% off the standard price.