Book your ticket for the UK touring exhibition Gladiators of Britain, opening in Dorset on 25 January 2025 and ending in Carlisle on 19 April 2026.

It's not surprising Valentinus lost his first gladiator fight. What's more surprising is that the fight happened, nearly 2,000 years ago, not in Rome or even Italy, but in Britain.

Valentinus must have been nervous when he put on his arm and shoulder guard that day, it was his first fight after all! As a retiarius, a type of gladiator fighting with a net and trident, with lightweight armour and no helmet, he would be facing a heavily armed, sword-wielding secutor in the arena. Even worse, this specific secutor, Memnon, was much more experienced than him, having fought nine previous bouts.

Valentinus's first fight

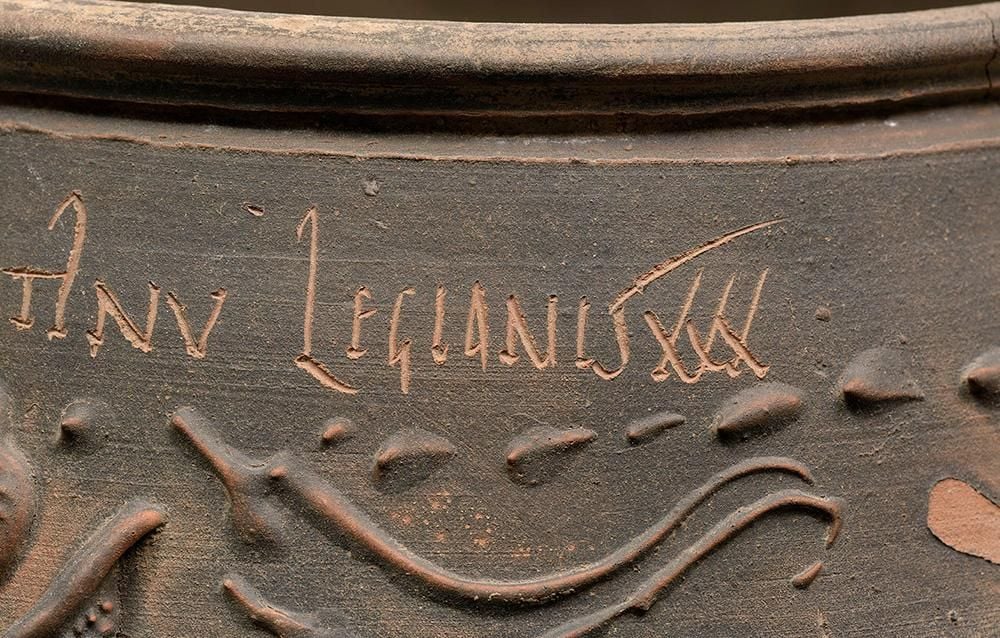

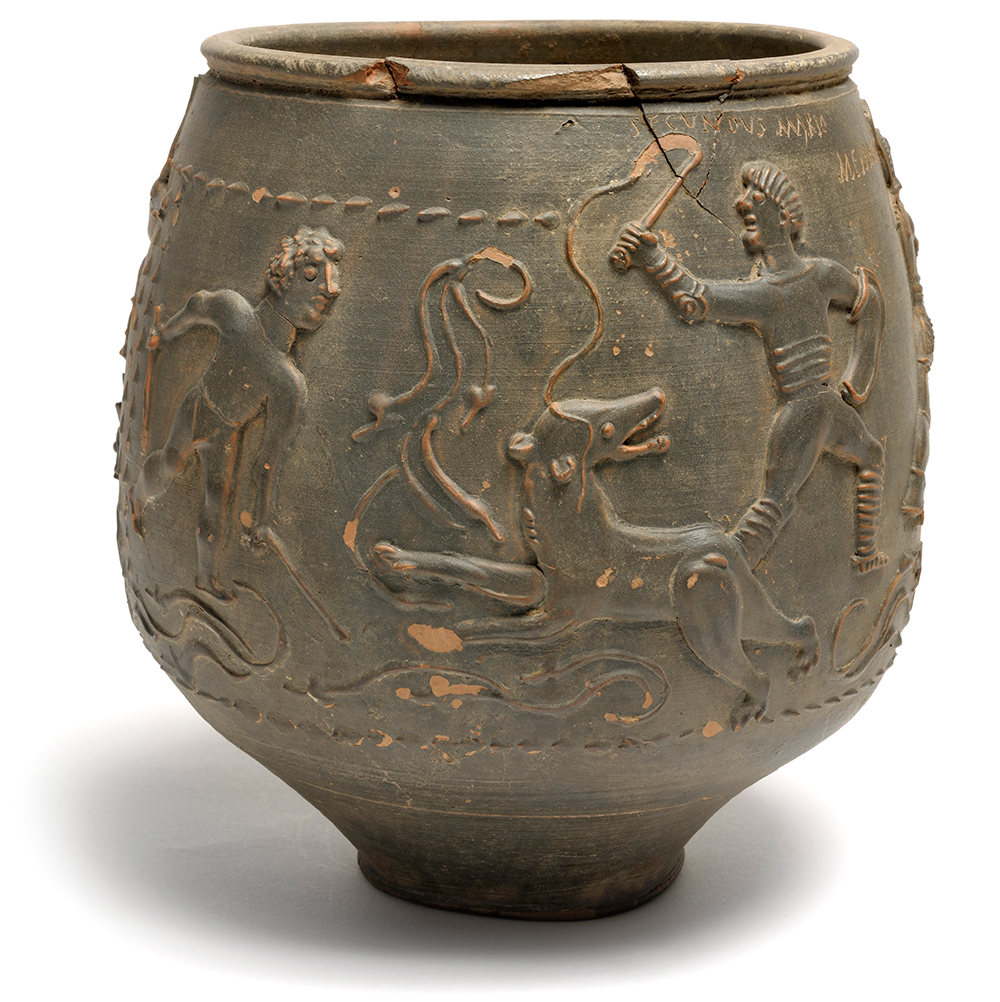

We know that Valentinus, perhaps unsurprisingly, lost his first fight. Valentinus and Memnon are depicted on the Colchester Vase, which preserves the final moments of the fight for us to witness: it shows Valentinus, with his head of curly hair, having lost his trident and signalling defeat by raising a finger at his charging opponent. The vase was made between AD 160–200 and later reused as an urn in a burial, but originally it was probably commissioned to commemorate the games at which Valentinus first performed in the arena. The vase was excavated over 170 years ago in the town of Colchester in Essex in the East of England, but has been hiding a secret ever since. Recent research has not only shown that the vase was made locally, but also that the inscriptions accompanying the images and telling us the gladiators' names were incised before the vase was fired, suggesting that Valentinus's first fight took place in Colchester.

Spectacles in the province

The origin of gladiator games is closely tied to Italy. They appear to have been adopted by the Romans from the Etruscans during the 3rd century BC and originally accompanied funeral ceremonies. They quickly became disjointed from their original context, however, turning instead into a way for the elite and later the emperor to show off their wealth and influence by gifting the games to the people. As an established part of Roman culture, such spectacles then spread all over the empire – including to Colchester.

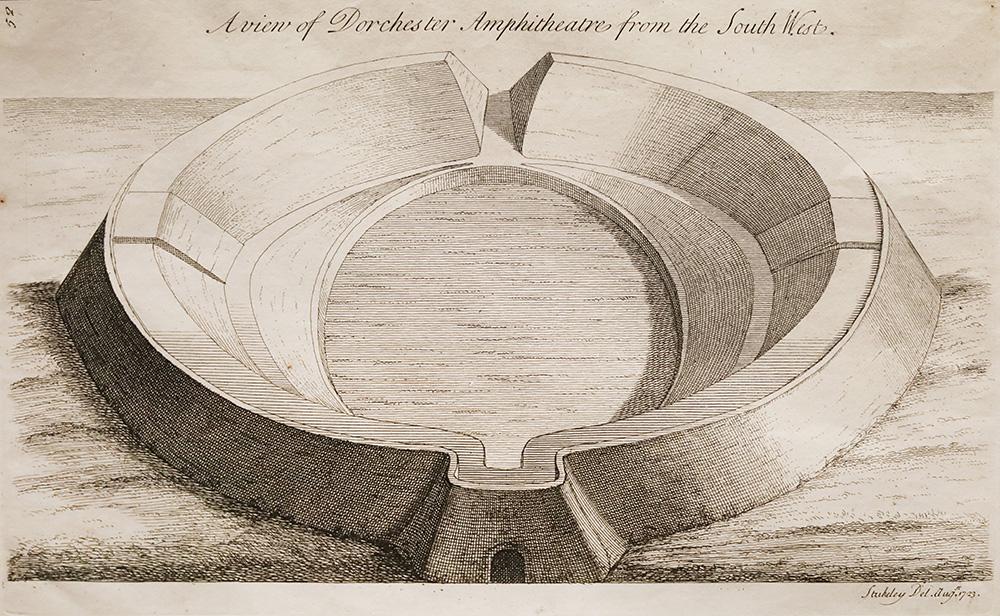

The indigenous settlement at Colchester, or Camulodunum, was first occupied by the Romans when a legionary fortress was established here in the AD 40s and later became the first capital of the Roman province Britannia. It was completely destroyed during Boudica's revolt against the Romans in AD 60/61 but by the time the Colchester Vase was deposited with the remains of its owner inside, it was once more a thriving town. Remains of the city walls, a theatre and the only Roman circus discovered in Britain attest to this high time, and an arena or amphitheatre would complete the picture, even if it has not yet been located. Numerous other Roman arenas in Britain bear witness to the spectacle culture here, from Durnovaria/Dorchester in Dorset all the way to Trimontium/Newstead in the Scottish Borders.

The largest known amphitheatre in Britain is in Chester and may have accommodated as many as 10,000 spectators. Britain's arenas were smaller than the magnificent amphitheatres in Italy – the Colosseum was the largest arena ever built in the empire and seated up to 80,000. They also sometimes looked a bit different. In Dorchester, for example, the Romans turned a Neolithic enclosure (henge), Maumbury Rings, into an arena, resulting in an unusual circular shape.

A day to remember

The games must have been a very special occasion for many spectators, and they wanted to remember it, just as we do today after visiting a concert or a sports event. Examples of merchandise relating to gladiators from Britain's Roman period are well-known. They range from lamps and cups to statuettes and knife handles and depict gladiators or take the shape of their equipment, particularly their helmets, which distinguished different types of gladiators. That such souvenirs were not only exported to the provinces but also made locally shows just how popular such spectacles were across the empire.

An oil lamp in the British Museum collection, for example, was made in the shape of a helmet worn by thraex ('Thracian') gladiators. Its beautiful green lead glaze gives it a certain air of luxury. It was made in Cologne around AD 200, on what was at the time the outskirts of the empire, but similar lamps were also made in Britain. Another find from Colchester, a bone figurine that may have been a knife handle, represents a murmillo type gladiator with his armour in great detail.

Despite the fact that such mementos are not uncommon in Britain and confirm how fascinated people here must have been with gladiators, it is very difficult to grasp the presence of gladiators themselves.

A dazzling display?

So far, Britain has not yielded a gladiator school, or ludus, like the one in Pompeii, for example, and no monumental tombstones for gladiators as we know them from other provinces. But the Colchester Vase sheds new light on another unique find in the British Museum collection, the Hawkedon Helmet, the only known piece of Roman gladiator equipment from Britain.

Found in a field in Hawkedon, Suffolk, its original context and how it ended up in that field remains a mystery, but its identification as a gladiator helmet is certain. It is large and heavier than a soldier's helmet and is comparable to the helmets found in Pompeii's ludus. According to new research it was made of brass, with tinning on the surface, mimicking gold and silver. This would have contributed to its visibility and dazzling effect in the arena. The metal composition also suggests that it was made on the continent, and that it may date to the time when the Romans conquered Britain (about AD 43–69), meaning that gladiator games may have been brought to Britain right from the beginning. Could the helmet have been worn where Valentinus later fought, in Colchester? It certainly seems possible considering the evidence of the Colchester Vase.

Forced to fight

After hiding in plain sight for decades, the inscriptions on the Colchester Vase now give us a – tantalisingly tiny – bit of additional information on some of the gladiators of Roman Britain; this is how we know that Memnon had fought nine previous bouts. We learn that Valentinus was 'of the 30th legion' (legionis XXX), which we know was stationed at Xanten in western Germany at the time the vase was made. But the inscription does not suggest that Valentinus was a soldier, rather that he was actually owned by the 30th legion. Some gladiators were prisoners of war or criminals and others will have taken up this career professionally, but many were enslaved, as Valentinus seems to have been. He may have been brought all the way from Germany and forced to fight in Britain's arenas.

Others may have been brought with him. Valentinus was probably part of a gladiator familia ('family'), a group of fighters belonging to the same gladiator school. He probably received specialist training to become a retiarius, and the owner of the school, the lanista, would have provided shelter and food – probably a lot of porridge! Yet, gladiators had a very low social status and very few rights, even if they were not enslaved. Their low status stands in stark contrast to the fame some gladiators reached. Graffiti inscribed by fans onto Pompeii's walls that count individual gladiators' victories and defeats show that some gladiators were admired almost like today's celebrity athletes. Valentinus may have reached a certain level of fame, at least locally, given that he features on the Colchester Vase with his name and military relation, but it is unlikely that this afforded him a more comfortable or self-determined way of life.

Beasts in the arena

While our knowledge about the everyday life of those who fought in Britain's arenas is sparse, we do know a little bit more about how their lives may have been lost. In a Roman cemetery excavated at York, many of the skeletons, buried there between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD, show injuries that suggest they were gladiators. On the pelvis bone of one individual are bite marks of a large animal – perhaps a bear or even a big cat. Exotic animals such as tigers and lions were imported over great distances for the beast hunts that took place in the empire's arenas, and one of these beasts may have made the long journey north, across the channel. Did Valentinus hear lions and tigers growl and pace in their cages at Colchester? He probably came close to a different fierce animal: in addition to Valentinus and Memnon, the Colchester Vase shows and names two more men, Secundus and Mario, who are shown baiting a bear. Bears may also have been brought to Britain from the continent, perhaps from the Germanic provinces. Could Valentinus and the bear have made the journey together, on boats down the Rhine and on bumpy roads to Colchester?

Valentinus lost his first fight, but it is unlikely that he also lost his life that day. The sponsor of the games decided over the life of a defeated fighter, but a trained gladiator was an investment that was not to be given up lightly, and Valentinus may have gone on to fight many more bouts in Britain's arenas. How might he have felt about his defeat being immortalised on the Colchester Vase? Perhaps he would have taken comfort in his legacy as one of the only known gladiators in Britain, whose fame has endured even beyond the collapse of empire he fought under.

Book your ticket for the UK touring exhibition Gladiators of Britain, opening in Dorset on 25 January 2025 and ending in Carlisle on 19 April 2026.