Discover the women who led the way at the British Museum.

From the first women to study in male-dominated reading rooms and the suffragists campaigning for women's rights, to the earliest women employees and a curious connection with the first woman to run for President in the US – women have helped shape the Museum since the start.

The first women visitors

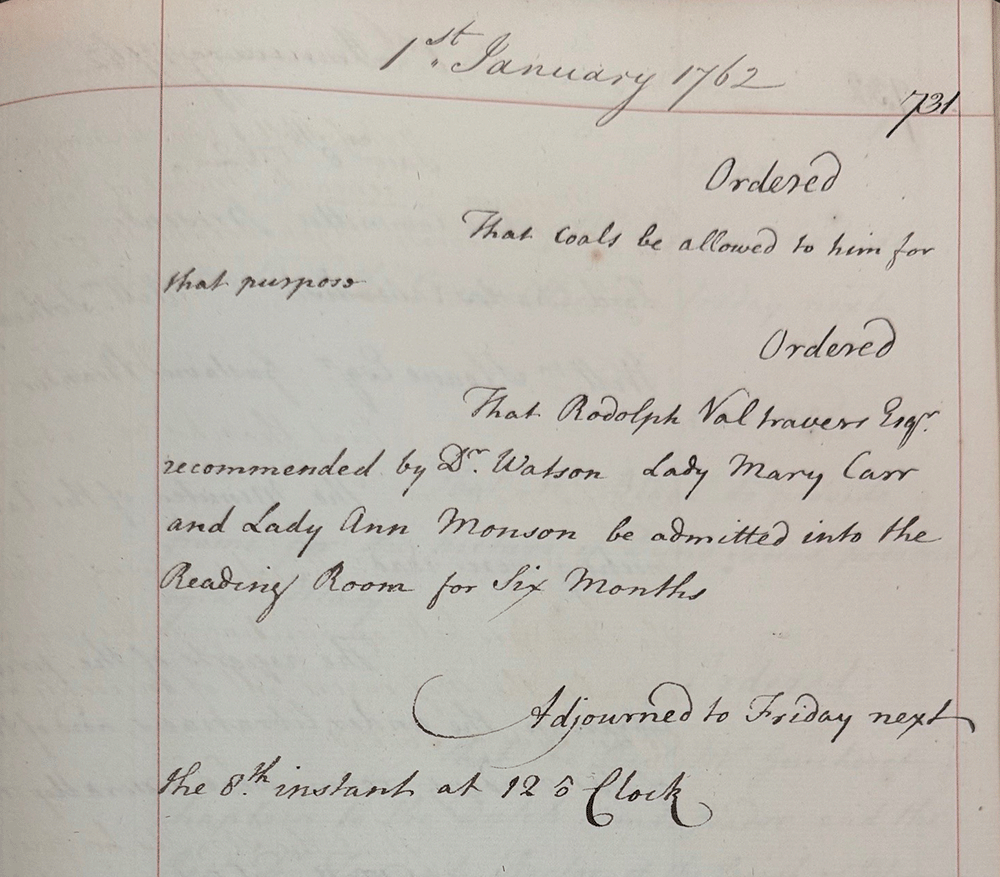

Opening in 1759, the British Museum was the world's first public museum. Alongside the displays showcasing the collection, the reading rooms were (and still are) a core part of the Museum. They were places of research and study, where scientists, philosophers, economists, political theorists and writers gathered to research, write and share ideas. Although women were welcomed to the Museum reading rooms right from the start, in practice they were spaces largely dominated by men. In 1762, the first women were recorded as using the British Museum reading rooms: sisters Lady Mary Carr and Lady Ann(e) Monson, from Raby Castle near Darlington in County Durham. They were granted permission to visit on 1 January that year, with readers' tickets which were valid for six months.

Lady Anne was a renowned botanist, said to have been recognised for her expertise by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. She was well known to the artist Mary Delany, who drew on her work to produce her famous flower collages. With links to the British Museum through her connection to naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, a Trustee, and Daniel Solander, who was employed as the Museum's first botanical curator in 1763, she travelled to South Africa and India, where she was able to collect botanical specimens. After collecting plant specimens and sending them back to England, she even had a genus of plant named in her honour.

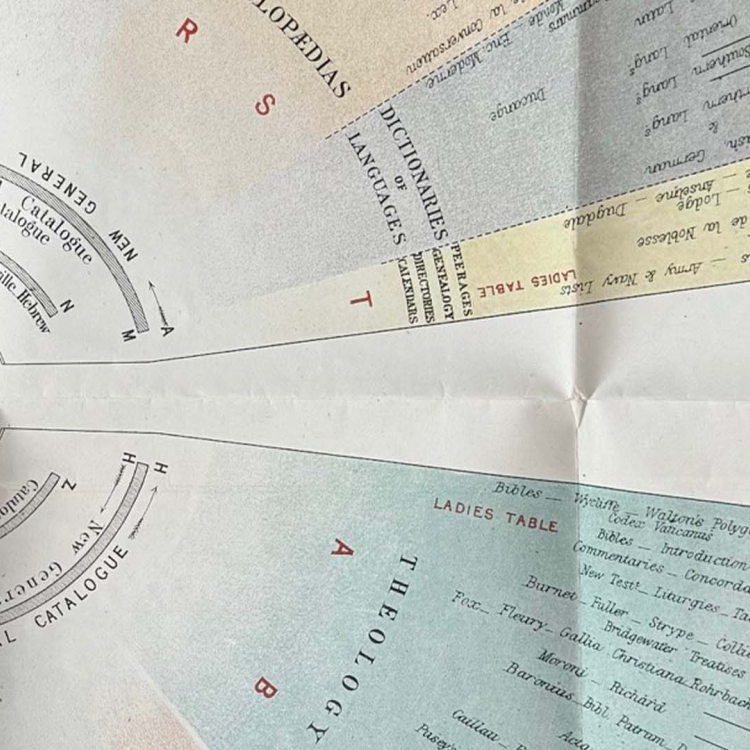

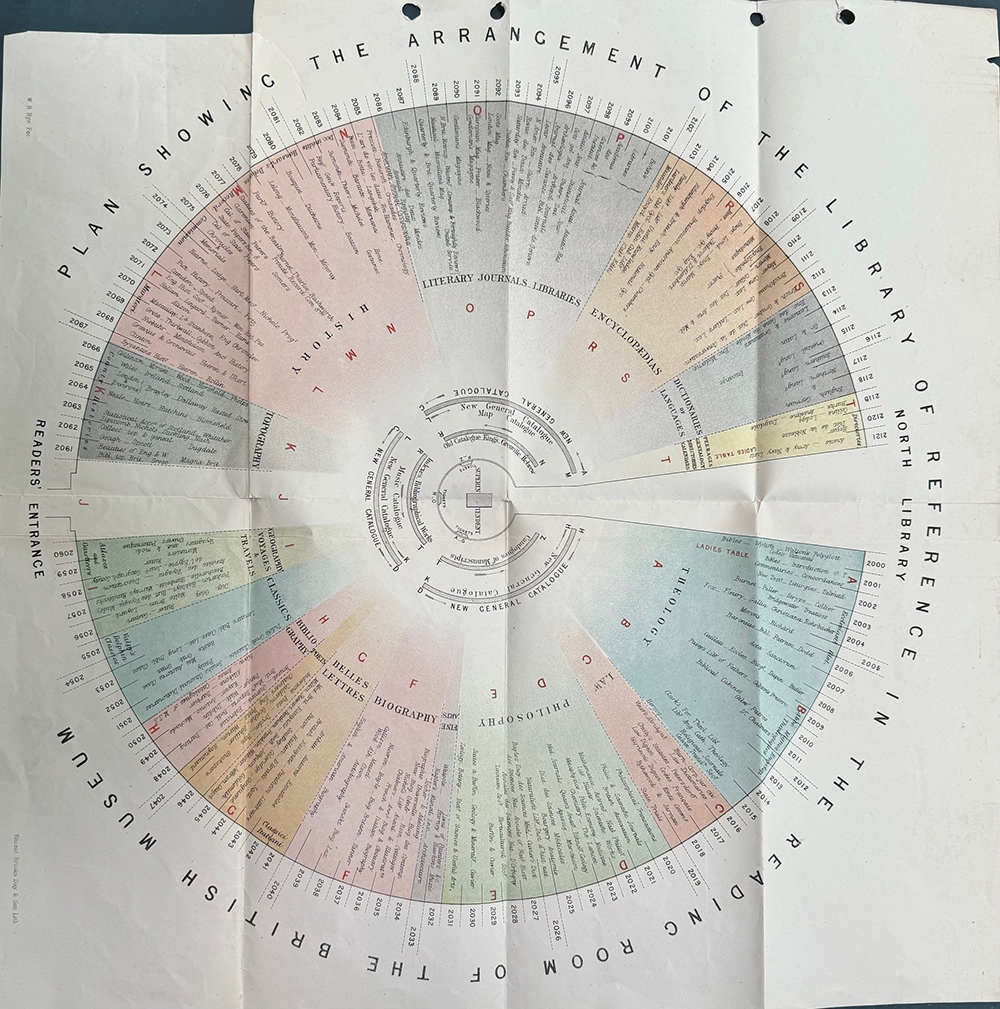

Women were known to sometimes complain about the behaviour of men in the room and were given their own tables in the new Reading Room when it opened in 1857. You can see from this plan that the ladies' tables were situated towards the back of the room, beside the entrance to the North Library.

Many women have frequented the Museum's reading rooms since the first one opened in 1759 to study and further their research, including children's author Beatrix Potter, suffragist Sylvia Pankhurst and writer Virginia Woolf, to name just a few.

Suffragettes in the Reading Room

(Estelle) Sylvia Pankhurst was a renowned socialist, activist and writer, and daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the British suffragette movement. Along with her mother and her sister Christabel, Sylvia founded the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), an independent women's movement which first met in her family house in Nelson Street, Manchester, on 10 October 1903. She played an active role in the movement, from creating their logo and producing various pamphlets and leaflets for the cause, to touring the industrial towns of England and Scotland to better understand the plight of working women. In 1908 Sylvia applied for a reader's ticket for the Museum's Reading Room, expressing a desire to study government publications and to conduct further research on the employment of women. She was instrumental in ensuring the law for women's suffrage was changed in 1918, with the Representation of the People Act, allowing women over 30 who were married or a member of the Local Government Register to vote, and then in 1928, when women received the same voting rights as men for the first time.

Suffragette 'outrage'

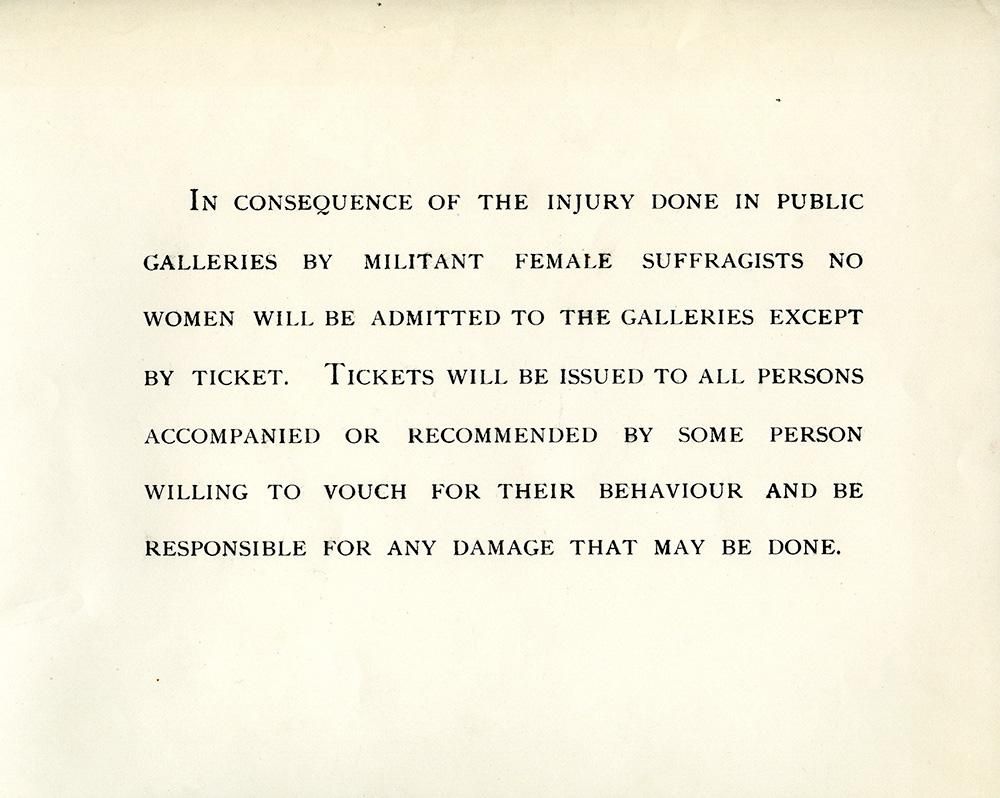

The Museum's Trustees were first alerted to the threat posed by militant suffragists (also known as suffragettes) at their meeting on 8 February 1913. The Director reported to the meeting that 'in consequence of the threatened recrudescence of militant suffragism' he had arranged with Keepers that attendants should be available to patrol galleries during meal-time absences of the police and commissionaires. He had also given instructions for the searching of bags and muffs (fur hand-warmers) in the Entrance Hall. The Commissioner of Police, who had raised his concerns with the Museum in relation to this threat, had approved the Director's actions.

The matter of militant suffragism was raised again at the Conference of Museum Directors on 8 April 1913. There had been an unsuccessful attempt at 'mischief' in the Museum on the 10 March and the meeting of Museum Directors was hastily convened, with the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in attendance, in order to discuss the question of 'precautions against attempts at outrage'. The proposal to close all museums and galleries in response to the threat was decided against, but on the condition that plain clothes detectives were to be drafted in to support the usual gallery warding staff. This inevitably came at a cost, and the Trustees discussed again, at their meeting on 24 May, the importance of this provision, with the Treasury agreeing to the additional expenditure until 30 June, to be extended again until 31 October, and then again until 31 March 1914.

On 10 March 1914, an 'outrage' (protest) was committed at the National Gallery, where suffragette Mary Richardson had slashed the painting The Rokeby Venus (1647) by Diego Velázquez with a butcher's knife. This prompted further fears of a potential attack at the British Museum, and the Director requested permission to ask the Treasury to sanction extending the presence of plain clothes detectives yet again. These detectives were to be 'familiar with the appearance of prominent female suffragists', and to be 'permitted to exclude without reason assigned women who had been convicted for participation in suffragist outrages'.

After the attack at the National Gallery, Robert Farquharson Sharp, Assistant Keeper of Printed Books and Superintendent of the Reading Room, was asked to supply details of anyone holding a reader's ticket with the name Mary Richardson. There were eight such names, and two were identified as possible culprits of the National Gallery incident, with a further reference to a Miss C Richardson (clearly a relation), well known in the Museum as a pigeon-feeder and thought to have connections to the Women's Suffrage movement.

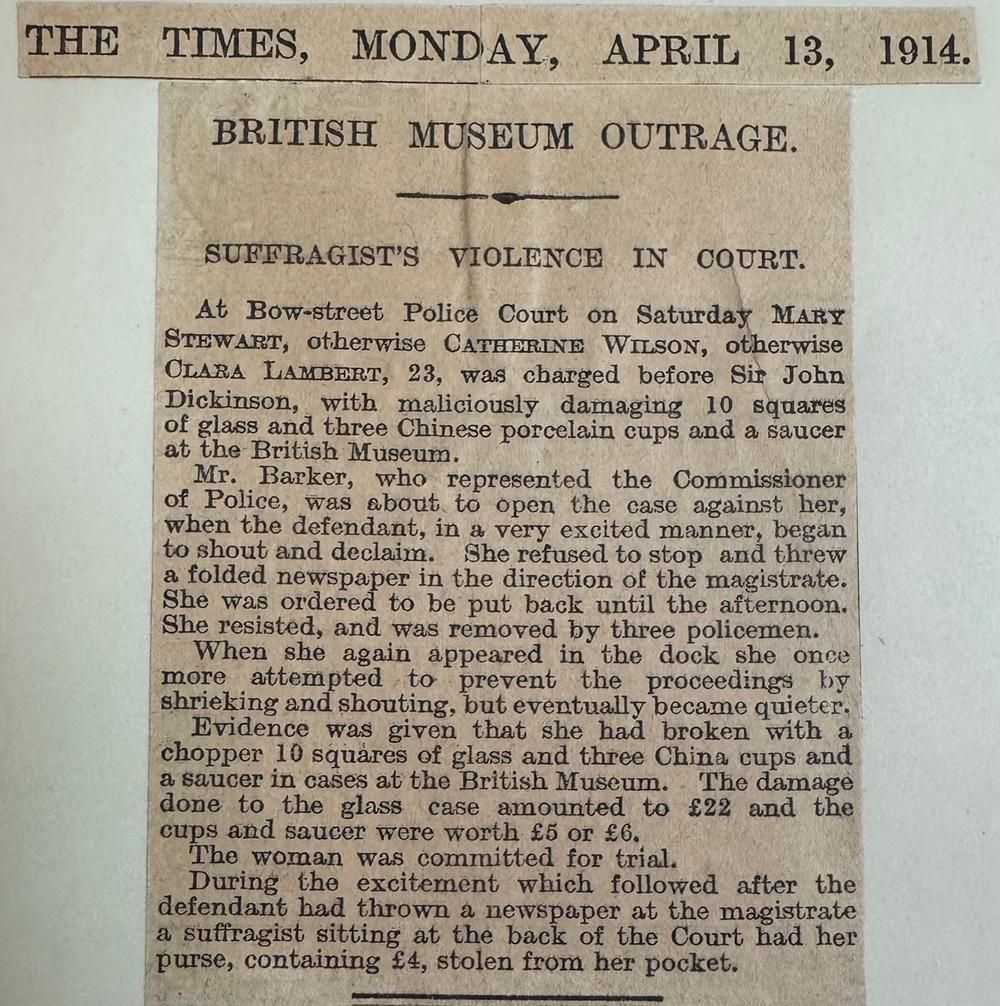

On 9 April, despite all the protections that had been put in place, there was a suffragist 'outrage' at the Museum. Miss Mary Stewart, also known by the names Catherine Wilson and Clara Lambert, armed with a butcher's cleaver, smashed ten panes of glass on a display case in the Asiatic Saloon. Causing £22 (over £2,000 in today's money) of damage to the case, she also damaged three china cups and a saucer before she was apprehended by a gallery attendant, who then handed her over to the on-site police. Appearing in court on 11 April 1914, Miss Stewart was defiant, shouting from the dock that she did not recognise the court's jurisdiction while Mrs Pankhurst and others were being tortured under the 'Cat and Mouse Act' and the 'devilish work of Mr McKenna', the then home secretary.

This account of the 'outrage' appeared in The Times newspaper on 13 April 1914. Following this action, women were no longer permitted to enter the Museum freely. They were to be escorted by men, or vouched for by male members of their families, in writing, before they could gain a ticket of entry. The restrictions were lifted on 20 August – although women still had to undergo handbag searches – and the additional police were stood down in September 1914.

The first women employees

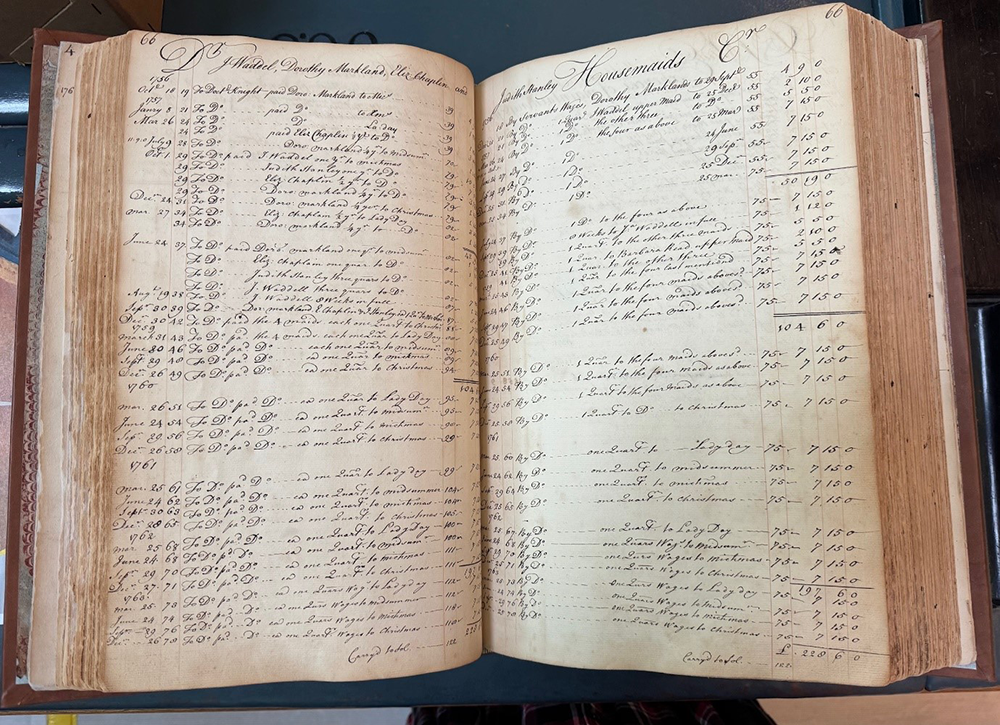

Women were employed at the Museum from its foundation, initially as housemaids, housekeepers and ladies' maids. Women typists were employed from the 1890s, and administrative clerks followed shortly after, along with saleswomen for the newly opened shops in the early 20th century. While women had been permitted to work unpaid in the Museum as academic lecturers and volunteers, it wasn't until the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 that the Trustees were permitted to employ women for curatorial or academic positions.

The Trustees began discussing the change in the law, and how women might take up curatorial roles in positions that had up to that point been dominated by men, in a fair and equitable way. In 1931, the first female curator was employed in the Department of Manuscripts as Assistant Keeper: her name was Margery Hoyle. At this point the Natural History Museum was part of the British Museum – they were a little quicker off the mark, employing their first women in curatorial roles in 1927, two in the Zoological Department and one in Entomology (the study of insects).

Dame Mary Smieton was the Museum's first female Trustee, taking up her role in 1963. She had been a career civil servant, first joining the service in 1925, and becoming Permanent Secretary to the Minister of Education in 1959, only the second woman to reach the rank of Permanent Secretary in the Civil Service. She had also played a key role in the Women's Voluntary Service (now known as the Royal Voluntary Service) and was a welcome female presence on the Museum's Board of Trustees.

As people are recorded in the archives by name only, further research is needed to understand the composition of staff, visitors and trustees by gender and ethnicity. Bonnie Greer is believed to be the first woman of African descent and the first person born in the United States to be appointed Trustee of the British Museum. She is also believed to be, along with Chief Emeka Anyaoku, one of the first people of African descent to be appointed Trustee, a position she held from 2005 until she served as Deputy Chair of the Museum from 2009 to 2013. She co-created and co-chaired, along with former Director of the British Museum Hartwig Fischer, the conversation series entitled The Era of Reclamation (2020), which is still resonant today.

A curious connection

Born in 1833, Victoria Woodhull was an American woman and well-known suffragist who became the first woman to run for President of the United States in 1872. As a campaigner for women's rights in the US, she caused a stir with her radical ideas: she was an advocate for the freedom of women to marry, divorce and bear children without social restriction or judgment.

She had a varied career, first as a travelling magnetic healer, then a spiritualist, and wrote many articles to promote her beliefs and further her causes. She is believed to be the first woman in the US to run her own brokerage firm on Wall Street, making her the first woman stockbroker. She garnered further attention when she decided to run for President, and is thought to be the first woman to do so.

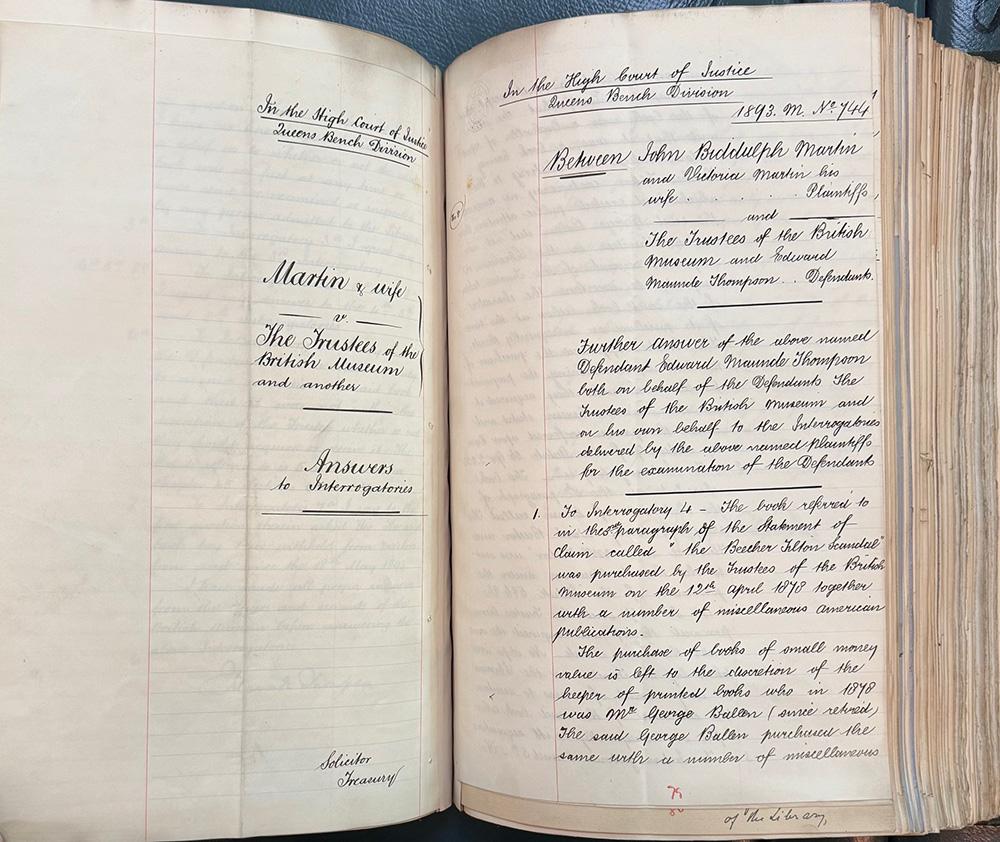

All this attention clearly led to trouble, and those wishing to undermine her began to publish libellous books and pamphlets in an attempt to sully her name. One such pamphlet ended up on the shelves of the British Museum library, and in 1894, Victoria's husband sued the Museum after the Trustees refused a request from him to take it out of public circulation. The court case was long and messy, and the Museum lost, meaning that the Trustees were responsible for the content of every item in the library collection, along with every other legal deposit and public library in the country. This would have been a near-impossible task and the Museum appealed the decision, finally overturning the ruling, much to the Trustees', and many other librarians' relief.

Conclusion

We may still be some way from having a woman President in the US, but closer to home women are helping to shape the future of the British Museum. Today just over 50% of visitors to the British Museum are women, and women also account for around 60% of the Museum's employees. Just under 50% of the Museum Trustees are women, including three new, recently announced Trustees: author and academic, Tiffany Jenkins; journalist and broadcaster, Martha Kearney; and broadcaster and writer, Claudia Winkelman.