This Disability History Month we explore the lived experiences of disabled people in ancient Egypt and how they were incorporated into ancient society at all levels, including the divine.

Disability has existed throughout human history and across the world, and ancient Egypt is no exception. Due to the arid desert environment of ancient Egypt, there are incredible levels of preservation, particularly of organic materials. Ancient art, objects and texts, as well as the remains of the people themselves, tell us much about disability in ancient Egypt. The objects and remains discussed below explore the lived experiences of ancient disabled people and relate to this year's Disability History Month theme of livelihood and employment. They show how disabled people were incorporated into society at all levels and in myriad ways, even from the early periods of Egypt's history.

Our understanding of disability and impairment today does not directly reflect how these conditions may have been understood in the ancient world. Many objects and human remains in the British Museum collection have a connection with disability, but the insights they provide on the history of disability have, for the most part, gone unnoticed. This blog looks at some of these objects and remains from a fresh perspective, bringing new stories of disability in ancient Egypt to light.

Dwarfism: early evidence for inclusion and influence

One of the most common depictions of physical disability in ancient Egyptian art is a condition known as dwarfism, which is often associated with restricted growth in a person's limbs and stature. While the conventions of Egyptian art resulted in the human body being depicted with standardised proportions and features, we see some individuals portrayed with physical differences. Some representations of dwarfism predate even the depiction of the pharaohs, with ivory or bone statuettes depicting men and women with dwarfism dating all the way back to the first centuries of the 4th millennium BC. An example can be seen in this ivory figure of a woman with dwarfism dated to approximately 4000–3500 BC, which is on display in the Early Egypt gallery (Room 64).

Often found in burials and ritual deposits, these statuettes are believed to represent guardians for pregnant women and babies. Some of these figures are shown holding infants. They indicate that people with dwarfism were valued community members and that they may have worked as caregivers for children.

People with dwarfism also appear in ancient Egyptian art and texts as members of the elite, working as priests or holding important roles in the pharaoh's court, such as 'Overseer of the Cattle' and 'Holder of the King's Linen'. The latter might not sound very important, but being close to the pharaoh's ear was significant. A recent study of Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC) art has identified over 115 depictions of people with dwarfism actively taking part in diverse roles across society, such as labourers, jewellers, animal handlers, entertainers and boat captains.

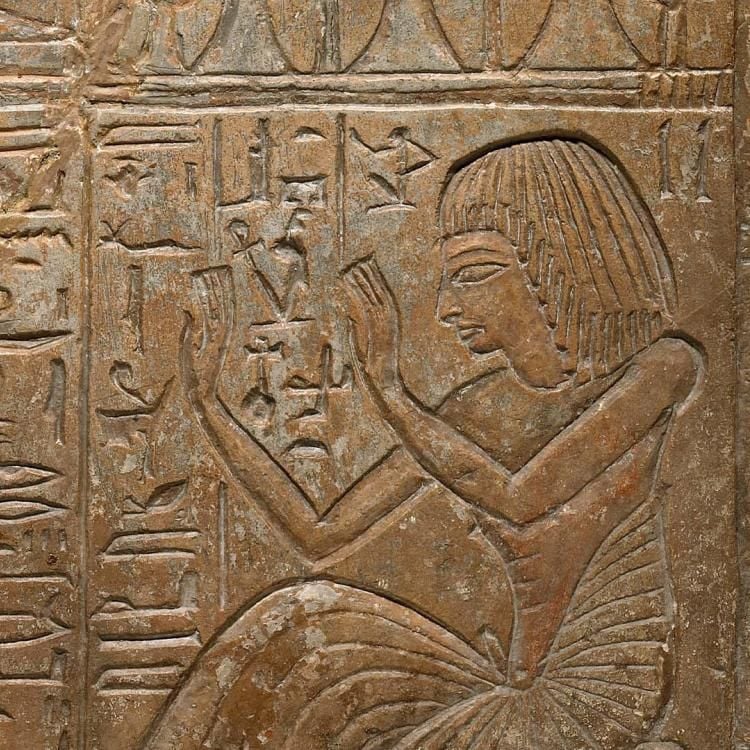

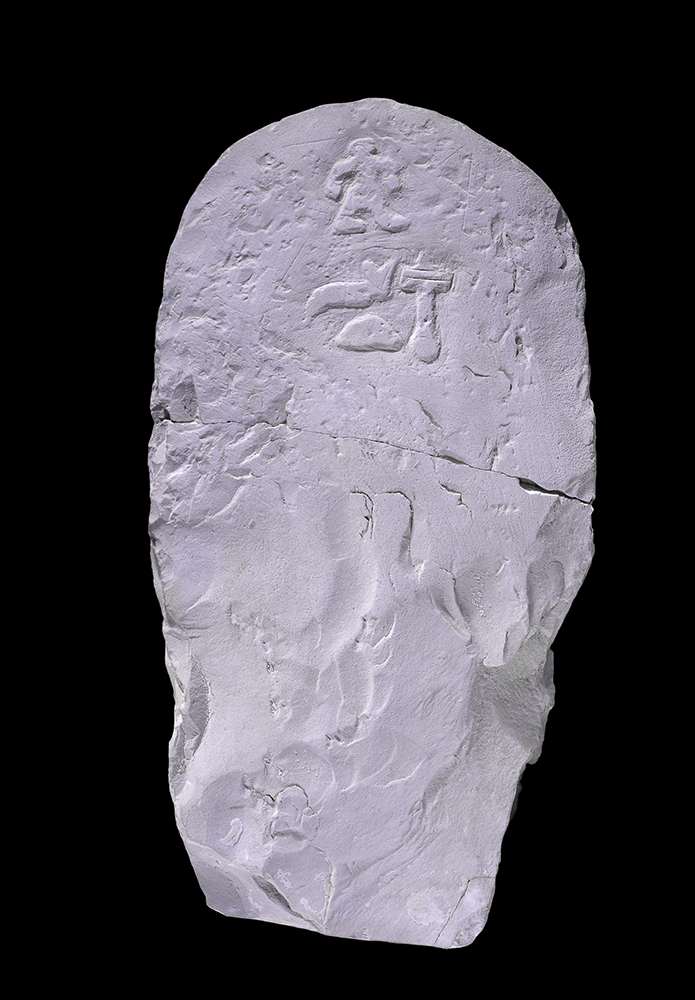

People with dwarfism in ancient Egypt sometimes presented themselves with their physical differences in both art and language. This stela (a stone or wood slab bearing inscriptions and/or images, often placed at a temple or tomb), also on display in Room 64, carries the name of a courtier: a man named Nefer (meaning 'beautiful'). The figure at the top of the inscription appears to represent the proportions of a man with dwarfism. This hieroglyphic sign would later be used to identify people with dwarfism throughout Egyptian history.

Bes: A popular protector

The Egyptian pantheon is host to a diverse range of deities, including the eye-catching god Bes, who is commonly shown as a man with dwarfism and, like other gods, with animal attributes. He is quite commonly depicted with lion-like features, most notably the ears, nose and tail. As a god responsible for the protection and safety of childbirth, families and the home, he uses these feline attributes to swiftly ward off illnesses and negative emotions, sometimes depicted as snakes or vermin – which domesticated cats in Egypt were known for catching. When he wasn't using his cat-like reflexes for protection, he would entertain and dance.

Bes did not have a dedicated temple; he was a god for the masses, worshipped within the household. Bes not only appears in his own statues – like this colourful example which shows the god joyfully dancing – but also on many everyday objects and items for protection. We see his face on babies' feeding bottles, bed posts, headrests, doorframes, rattles, jewellery and cosmetic items, such as this cosmetic jar which is on display in Room 61. Recent research also suggests that some women may have had the god tattooed on their body! In this way, Bes was someone with dwarfism who was familiar and present to the everyday Egyptian.

Blindness and partial sight in ancient Egypt

There are many depictions of blind and partially sighted people in ancient Egypt. One can be seen in a limestone relief from el-Amarna, which dates to around 1340 BC, currently on display in the Egyptian sculpture gallery (Room 4). It shows five blindfolded female musicians believed to be three singers and two seated harpists. In ancient Egypt, blindness was commonly associated with musicians, especially harpists. Typically, these individuals are shown with a singular line indicating the eye instead of the typical full-frontal open eye or, as is the case here, blindfolded. There is some debate over whether this blindness was a representation of reality or meant to be symbolic. Whether realistic or not, what we see in these examples is blindness or partial sight being accommodated and valued, and the possibility that disabled people were employed in positions that enabled them.

Another object associated with the experience of blind and partially sighted people in ancient Egypt, is a limestone stela belonging to Neferabu. Probably erected as an offering at Thebes and dating to 1292 to 1189 BC, the stela petitions the god Ptah for restored vision. In it, Neferabu confesses that he swore falsely by the god and that his punishment was 'to see darkness in the daytime'. Neferabu petitions for Ptah's mercy and for his vision to be restored. While some scholars suggest this 'blindness' was metaphorical, if actual, the stela and several others like it suggest that it was believed visual impairment could be inflicted as a form of punishment by the gods and that the divine could provide healing. We know from Neferabu's tomb that he was an artisan who most likely worked in tombs, so sight loss would have impeded his ability to do this work and might have been an occupational hazard.

Harpocrates: A God of cerebral palsy?

Harpocrates is a child deity worshiped primarily during the Ptolemaic Period in ancient Egypt (when Egypt was ruled by the Greeks), and spread beyond the Mediterranean world (664 BC – 2nd century AD). As the son of Isis and heir of Osiris, he was the child manifestation of the god Horus. He was considered the god of secrets, confidentiality, silence and the embodiment of hope. Harpocrates was also seen as the protector of mothers and children and of abundance and fertility. Harpocrates is described by the ancient Greek historian Plutarch as 'prematurely delivered and lame [weak] in his lower limbs'. There are numerous statues, figures and amulets portraying Harpocrates, such as this copper alloy figure. Dr Morris' recent study, incorporating her own lived experience, has explored the possibility that he shows signs of having cerebral palsy.

In some statues of Harpocrates, the positioning of his legs and hands, when traditionally thought of as being seated, are different from other images of gods and people in seated positions. For instance, his arms and hands appear to be parallel to his legs and torso despite the bent positioning of his legs, and his legs are sometimes either positioned out to the side or twisted behind him. Cerebral palsy has not been previously associated with his body positions. However, Harpocrates' posture in such examples resembles a crouch gait commonly seen in people with certain types of cerebral palsy. The god also appears in a half-crawling or half sitting position, or listlessly breastfeeding. There are also figures in which he is sitting or riding on the back of animals such as geese, horses and elephants, who are perhaps symbolically acting as mobility aides. Harpocrates was occasionally depicted with his worshippers or priests, who in some cases also appear with body positions possibly associated with cerebral palsy, such as the hand positions seen in this figure of a priest.

Harpocrates and Bes are uniquely similar in that they may both represent disability within the Egyptian pantheon of gods. They both functioned in a healing or protective capacity, particularly for mothers and children, and both had a masculine and feminine counterpart – Harpocrates and Harpocratis; Bes and Beset.

Broken bones and societal care

Some of the Museum's displays include human remains. These provide insights that cannot be gained from other sources, telling us about past people, the way they lived and the societies to which they belonged. Among those in Room 63 is a femur bone – the long leg bone connected to the hip. These remains were excavated from Abydos and likely date to the Late Period (664–332 BC). Recent examination suggests these may be the remains of a person in their late teens or early adulthood. The femur shows a healed misaligned fracture, which resulted in one leg becoming shorter than the other because of the overlap in the two halves of the bone. Today this kind of break takes approximately 3–6 months to heal with surgery. In ancient Egypt, there was no way of realigning the two halves and recovery and healing would have been much harder, often resulting in misaligned bones and shortened limbs.

The shortened leg would have directly affected this person's mobility. They might also have experienced chronic pain around the fracture and in other parts of the body such as the lower back, hip, knees and ankles due to the position of the fractured limb. We know from other examples, like the adaptive sandals of Tutankhamun which had a strap to help stabilise and protect his foot, that the ancient Egyptians had adaptive footwear and other mobility aids. These aids and adaptations were used during people's lifetimes and were also buried for use in the afterlife, meaning that disabled people were recognised and accommodated for in death. Recent studies suggest that remains like these are important for investigating social care in the past, as – while it's difficult to tell without their complete skeleton or burial goods – it's likely that this individual received a great deal of care.

A cartonnage toe: striding across life and death

This remarkable object comprises a copy of the lower part of a foot and the big toe believed to have been created no later than the 6th century BC. It is akin to a 'prosthetic' toe and is made of cartonnage (a technique similar to papier mâché), which was typically reserved for housing the body in burials. The loss of the big toe would have impaired balance, impacting everyday activities and livelihood. The Egyptians developed extensive medical knowledge, and perhaps this is why a replacement toe was made. There are several holes piercing the cartonnage to attach it to a person's foot, and although we cannot be certain this toe was used in life, being made of cartonnage suggests its use in funerary practices.

In ancient Egyptian beliefs it was important for the body to be perceived as whole for the afterlife. In Egyptian mythology, the body of the god Osiris had to be reassembled after his murder at the hands of his treacherous brother Seth. Osiris was resurrected and became ruler of the afterlife. All Egyptians aimed to be reborn after death like Osiris. In this way, the cartonnage toe is less of a like-for-like replacement and rather can be seen as a celebration of this process of life, death and renewal which was central to the Egyptian conception of the world. It can be seen on display in Room 63.

Conclusion

The stories recounted above are just a few examples that demonstrate that, for the ancient Egyptians, disabled people were an integral part of society: they were incorporated into Egyptian society at all levels and even deities could share their embodiments. Through these objects and remains we can catch glimpses of the importance of societal care within communities and, crucially, into the lived experiences of disabled people in ancient Egypt.

Disabled people have always been present and active in society. Many specialists and experts around the world have started to investigate representations and lived experiences of disability and care in the past through archaeology and museum collections. The objects and remains highlighted here demonstrate some of the stories we are uncovering and hint at the discoveries that might be made in the future. We hope that these stories will demonstrate to everyone that disabled people have always existed and been part of the story of humanity, and empower disabled people to see themselves in history, and to continue making it, thousands of years into the future.

About the contributors

About the contributors

Dr Alexandra F Morris and Kyle Lewis Jordan are Egyptologists with a specialist interest in disability in the ancient world. They are working with colleagues at the British Museum on a wider project which will highlight histories of disability in ancient Egypt and beyond.

Dr Morris is Lecturer of Classical Studies at the University of Lincoln and President of the Museum Education Roundtable. She is also a co-founder of the UK Disability History and Heritage Hub, co-chair of CripAntiquity, and sits on many advisory boards and research groups dedicated to disability. She has cerebral palsy and dyspraxia.

Kyle is an early career archaeologist and curator who specialises in the study of disability in antiquity, also born with cerebral palsy. He has curated displays on disability at the Ashmolean Museum and Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford as part of Curating for Change and is currently guest curator for the Verulamium Museum in St Albans.