Gossip about Anne Seymour Damer's sexuality nearly wrecked her relationships and reputation, but in this queer love story, love beats scandal.

'Social media' ruined lives in the 18th century, just as it does today. Anne Seymour Damer (1748/9–1828) was a sculptor (a highly unusual career for a woman artist at the time) and an aristocrat, which made her a part of celebrity culture and particularly exposed to gossip. Damer was also the subject of scandal because of her intimate relationships with other women. One of her contemporaries, the writer and literary hostess Hester Piozzi, described her as 'a lady much suspected for liking her own sex in a criminal way'. Damer was repeatedly labelled as a Sapphist. The term was an allusion to the ancient Greek poet Sappho; famous for her love poems, many of them addressed to other women, Sappho was beginning to be seen in this period as the original lesbian (a term drawn from her birthplace of Lesbos). The gossip put Damer's reputation at risk, but also sabotaged her chances of finding – and keeping – love.

About Anne Damer

Born in Sevenoaks, Kent, Damer's childhood and youth seem to have been happy, surrounded by loving family and friends. She came from a wealthy and well-connected background, which made it easier to pursue her passion for sculpture: she had access to lessons in drawing, modelling and even in anatomy – a subject most women weren't allowed to study. Her brother-in-law, the Duke of Richmond, had a sculpture gallery with casts of Greek and Roman statues – a great resource for a young sculptor wanting to follow classical models. Her father's cousin, Horace Walpole, included her works among the treasures of his art collection at his Georgian Gothic revival house Strawberry Hill in Twickenham – home to an increasingly important collection of paintings and objects – and praised her in his writings about art history.

18th-century social media

As an aristocrat, Damer was an easy target for 18th-century 'social media'. Her marriage to the Honourable John Damer (aristocrat, gambler and all-round bad lot) was an unhappy one. The couple separated after seven years and John took his own life in 1776, in part because of his gambling debts. After his death, Anne Damer was attacked in the press and in satirical poems. She was accused of being an uncaring widow, too easily consoled over her husband's death by the company of other women and, euphemistically, 'joys which blooming widows share'; there were hints and outright allegations that she'd had sexual affairs with women in Italy, and even that she'd eloped with another aristocratic woman (this one definitely wasn't true, but it circulated anyway).

Anne Damer the sculptor

During the 1780s, Damer increasingly devoted herself to sculpture. Her works were on show at the Royal Academy, where she was an honorary exhibitor (honorary because she wasn't a professional artist; to work for pay would have compromised her social status). She also moved from working in wax or terracotta to sculpting in marble and bronze, a sign of her seriousness as an artist. This full-length marble statue from the late 1770s, by her former sculpture tutor Giuseppe Ceracchi, shows Damer as the Muse of Sculpture. Ceracchi's portrait makes a statement about Damer's importance as an artist, but it's also an idealising and somewhat impersonal image: she's holding a sculpted figure but is not shown at work on it. Now in the British Museum, the statue used to stand in the main entrance hall, but was moved to one of the upper galleries in the late 1960s.

Anne Damer meets Elizabeth Farren

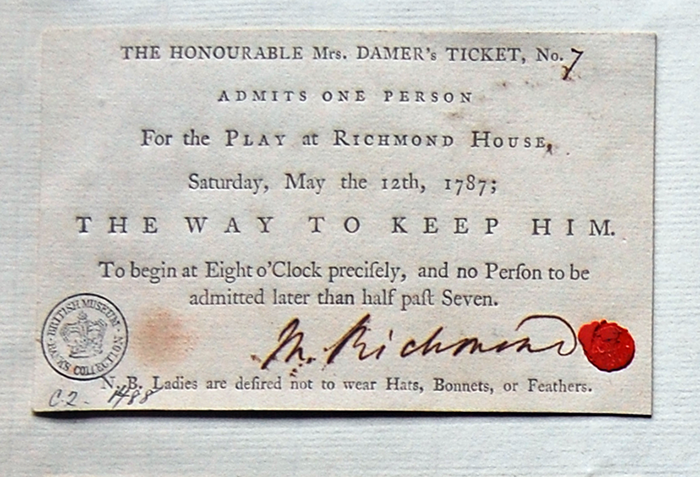

The attacks on Damer's private life mostly went quiet in the 1780s, as the scandal of John Damer's death receded, but her public image was still a complicated one. This unflattering caricature from 1787 shows her as a performer in The Way to Keep Him, staged at her brother-in-law's private theatre at Richmond House. Private here does not mean intimate: this was a high-profile event, attended by the aristocracy and other powerful figures. Tickets were not on public sale but given to friends by the performers, as the image here suggests. Reports of the occasion commented in detail on the elaborate costumes and (real) diamond jewellery worn by the performers; some of Damer's artworks were part of the set. The caricature shows both the actors and the audience as puffed-up, ridiculous figures making a spectacle of themselves in their outsized wigs and costumes. This theatrical production is where Damer first met Elizabeth Farren.

Rumours about Elizabeth Farren

Farren was a popular comic actress who coached the aristocratic players for the Richmond House event: she and Damer became close as a result. Damer made a marble bust of Farren as Thalia, the Muse of Comedy in Greek mythology, which is now in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG). As of last summer, the bust is part of the central display in the NPG's remodelled Entrance Hall; a welcome step in making Damer's art better known.

Damer's intimacy with Elizabeth Farren attracted scandal, both in gossip circles and in print. Rumours circulated about the rivalry between Damer and their friend Edward Smith Stanley, the 12th Earl of Derby, for Farren's affections. Emma Donoghue's novel Life Mask (2004) gives a vivid account of this triangular relationship (historical spoilers: the Earl gets the girl). A satirical pamphlet at the time suggested that Farren felt more pleasure from Damer's touch than she was likely to experience on her wedding night with Derby. A nasty little poem (written by William Siddons, the husband of the famous tragic actress, Sarah Siddons) warned that Farren's already precarious social reputation as an actress would be destroyed if she continued to be involved with Damer: 'Her little stock of private fame / Will fall a wreck to public clamour.' Recalling the scandal some years later, Hester Piozzi noted in her diary: ''Tis a joke in London now to say such a one visits Mrs Damer.' Damer's relationships with women were so notorious that anyone in her social circle risked being 'queered' by association.

18th-century gossip

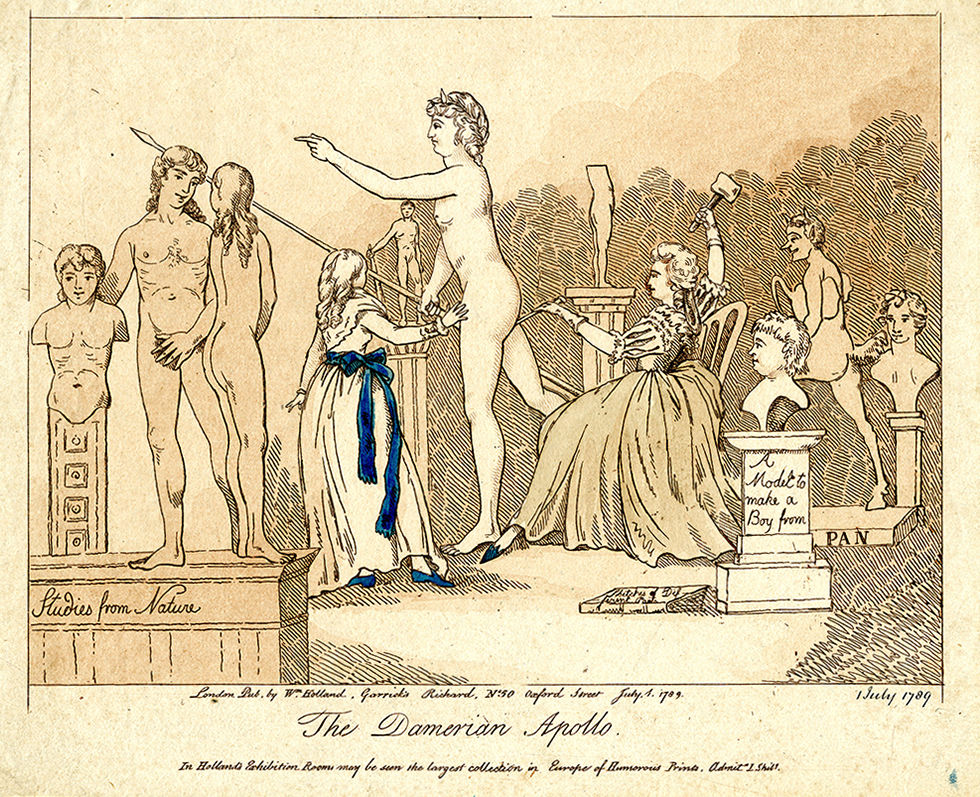

Eighteenth-century gossip and celebrity culture made it hard for anyone in the public eye to have a private life. This was (as it is today) particularly true for women, whose behaviour was always more strictly policed than men's. Damer's public identity as a sculptor also exposed her to satirical attacks. She had been commissioned to make a 10-foot high statue of Apollo for the roof of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane – and this 1789 caricature, The Damerian Apollo, presents her as unfeminine, immodest (that naked male figure!), a phallic woman or a ball-breaker (look what she's doing with that chisel!). We don't know for sure if the statue at the Theatre Royal looked like the one here, however, because it was destroyed when the theatre burned down.

My dear Soul

Anne Damer's last love was the writer and intellectual Mary Berry (1763–1852), and the relationship between them was central to both their lives for nearly 30 years. Introduced by Horace Walpole, the two women bonded over a shared love of classical Greek and Latin language and literature. The only image of them together, a beautiful and tender pencil drawing, shows them sitting in a library. Berry called Damer 'my dear Soul', and wrote to her 'what real home has my mind on Earth but yours?'

The gossip machine that wrecked Damer's friendship with Farren also put a strain on her relationship with Berry. When the rumours about Damer's intimacies with women started up again in the early 1790s – in part because of her connection with Farren – Berry and Damer had to separate for a while and be cautious about not spending time alone together. Damer wrote to a friend, Edward Jerningham, asking him to hire someone to keep an eye on the newspapers for her in case of further attacks.

Mary Berry's letters to Anne Damer

You need hardly have told me (tho' I like to hear it) that your soul when unconfined flys to me, for I have felt it hovering about me a hundred times here, in all my walks alone, whenever contemplating your favourite seat, always when going to bed at night (my constant opportunity of reading over your letters)

Excerpt from Mary Berry's letters to Anne Seymour Damer, as recorded in Damer's notebook

Mary Berry: Anne Damer's last love

Horace Walpole's death, in 1797, though sad, as he and Damer were close, enabled Damer and Berry to be near each other without provoking further scandal. Walpole left Strawberry Hill to Damer, and the house next door, Little Strawberry Hill, to Mary Berry and her sister Agnes. Walpole's Will seems to me an act of queer kinship, which makes possible the intimacy of this living arrangement for Damer and Berry – two women he loved, who loved each other.

A private love

Anne Damer wanted her correspondence to be destroyed after her death, and few of her letters survive. As Clare Barlow, curator of the Tate exhibition Queer British Art 1861–1967 (2017), says, the history of queer lives is a history 'punctuated by dustbins and bonfires'. Berry kept some of Damer's letters nevertheless, saying she couldn't bring herself to destroy the evidence of such devoted affection; the letters that survive are now in the British Library. Traces of Damer and Berry's relationship can also be found in Damer's notebooks, now in the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University. These four small notebooks are made up of extracts from Berry's loving letters to Damer, alongside quotations from the classical Greek and Latin authors they both loved.

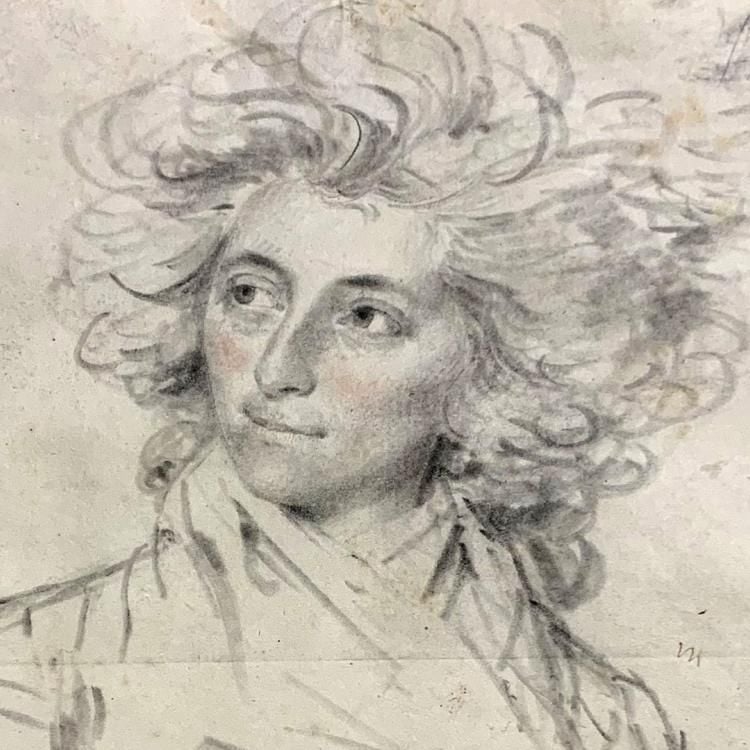

Despite her very public life, there's so much we don't know about Anne Damer. In LGBTQ+ history, we're used to the idea that someone's private papers can reveal the queer truth behind their straight public image, but that's not the case here. Damer's reputation for Sapphism could hardly have been more public or more scandalous. Her notebooks tell a quieter story about love between women, one that we have to read in fragments. I love this profile sketch by John Downman in the British Museum collection, both because it shows Damer as an artist at work, and because her face is hidden from us: in the end, the joys of her private life remained her own.